With the easing of lockdown measures now in full swing we are coming to the end of the largest global work experiment we’ve ever seen.

As I’ve written previously it is vitally important to understand that this hasn’t been a true remote work experiment, rather it has been an enforced work from home experiment happening at the same time as the suspension of many of our civil liberties. Any evaluation has to take into account the stress and turmoil that many people have been living with and the subsequent impact on their productivity.

COVID-19 has shown us what we can accomplish when we don’t project plan something to death.

Just days after the virus was declared a pandemic many companies managed to get upwards of 90% of people working remotely. Jobs that we never imagined could be performed remotely— jobs which people were told couldn’t be performed remotely – suddenly and successfully were handled from home.

We’ve finally challenged the office orthodoxy, and it’s our choice where we go from here.

Stay remote?

Back to the office?

Or adopt a hybrid model.

For a fairly conservative view you could look at the new report from Xerox, The Future of Work in a Pandemic Era. Designed to uncover how IT decision makers are addressing these major considerations in a highly fluid environment 600 IT leaders were surveyed.

Depressingly, it estimates that 82 percent of the workforce in respondents’ organisations will have made a full return to the office in 12 to 18 months. For those of us who were asking whether offices would still exist that’s a healthy vote in favour of the status quo.

To be fair, the report also notes that the softening of employer attitudes toward remote working – with managers realising ‘hey, they actually do work without us bosses looking over their shoulder’. It’s this realisation – and the sight of scores of managers littering LinkedIn and Twitter with excitable Zoom and Teams selfies – that could usher in the hybrid workplace with employees working remotely all, some or none of the time depending on their role.

It’s always useful for us remote work laggards to listen to people who have been working in a distributed fashion long before the pandemic.

As Matt Mullenweg discusses in his conversation with Sam Harris, he has seen companies make the transition for small (10 people) to large (1500+) with an evolving set of work principles.

As Matt says – any company who can enable employees to work in a distributed environment now has a moral imperative to do so. Forcing a commute is worse for the planet and worse for personal wellbeing. It’s no longer the act of a responsible employer.

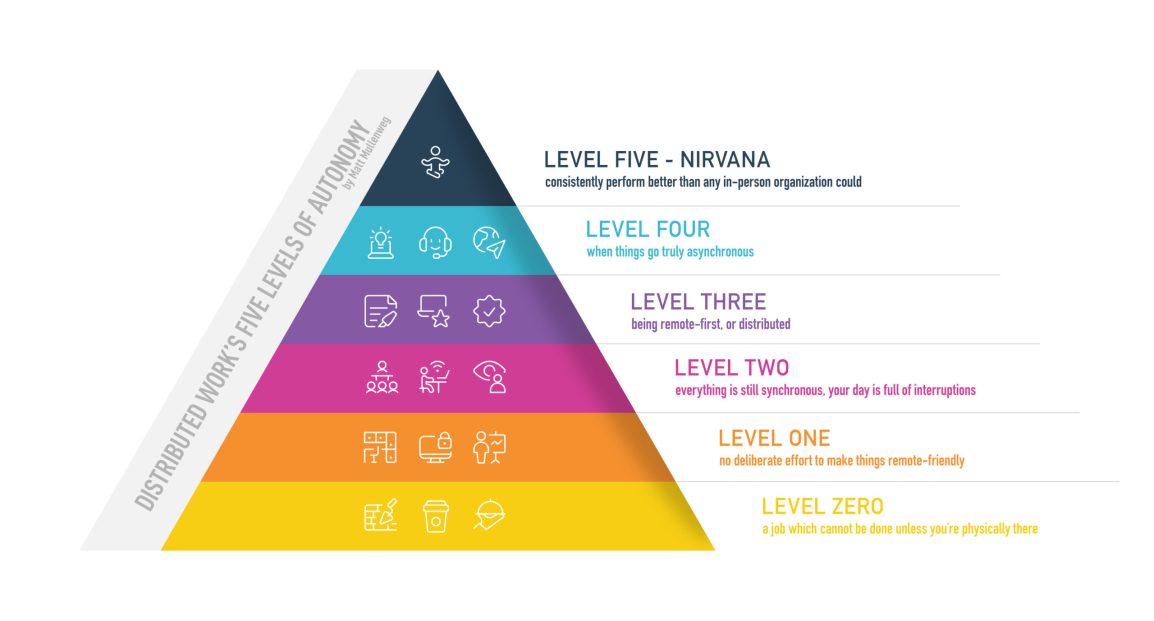

Matt has outlined five levels of distributed work that are useful to reflect upon:

- Level Zero autonomy is a job which cannot be done unless you’re physically there. Many companies assumed they had far more of these than they did.

- The first level is where most businesses were pre COVID, 98% reckons Matt. There’s no deliberate effort to make things remote-friendly. Work happens on company equipment, in company space, on company time. Level one companies, says Matt, were largely unprepared for this crisis.

- Level two is where most of us landed during lockdown. Doing what you did in the office, just remotely. Matt likens this level of maturity to the situation in the early 1920’s when radio drama started. Performers would literally recreate plays – but just on the radio. There was no taking advantage of the new technology or innovating the medium. Importantly Matt points out that this can be less productive than level one as we explore and get distracted. His advice – push on – nirvana lies aheads

- At the third level, you’re really starting to benefit from being remote-first, or distributed. People invest in better equipment. It’s where teams start to collaborate on shared documents or build business cases during the meeting.

- Level four is when things go truly asynchronous. You evaluate people’s work on what they produce, not how or when they produce it. Employee retention goes way up, and you invest more in training and coaching. Real-time meetings are respected and taken seriously, almost always have agendas and pre-work or post-work.

- And level five, Nirvana This is when you consistently perform better than any in-person organisation could. It’s when everyone in the company has time for wellness and mental health, when people bring their best selves and highest levels of creativity to work every day.

The most important lesson I take from Matt is that there will be a pain barrier to push through at Level 2.

As someone who took a extended break from work at the beginnings of COVID I returned to find people saying they were overwhelmed, in continual back to back meetings , and working 12 hours days. That this has become acceptable in such a short period of time is a form of madness , and is wholly unsustainable if we are to push forward and mature our approach to distributed work.

In fact the terminology of remote work is itself unhelpful almost framing the solution as either office or home based. As Stowe Boyd suggests perhaps we need to turn the thinking and terminology around and drop both the ‘hybrid’ and ‘remote’ terms. As he says, let’s call the model that leads to higher engagement and productivity ‘minimum office’, rather than zero office and allow each person to define what that minimum is for them and their team.

We do need to avoid simplistically calling for the death of the office (although let’s be clear – it’s dying). Equally we need to resist the corollary of “get back to the office”. What about the city centres? What about the shops and spaces that have supported us the past few months? It would be remiss of us to exclude our local communities from this conversation.

This isn’t a binary choice between the office and remote work. Instead we must consider what work used to be, what it is now and what it could be in the future.

That – and that alone – should form the basis of a discussion of where the work is actually done.