Written by: Frank Caruso and Chris Kotowicz

Equity investors are trying to figure out whether steep share-price declines have led to attractive valuations, given mounting threats to fundamental business performance. The answer varies from company to company and requires an active equity investing approach to separate winners from losers.

Stock markets are still reeling from this year’s dramatic events. The bull market of 2020–2021 was driven by massive liquidity injections and low interest rates, which inflated valuations of high-growth companies compared to more mature peers. Unfortunately, the same policies that fueled asset prices prompted inflation in goods and services prices. By mid 2022, central banks started raising interest rates sharply in an effort to curb the strongest inflation in the real economy since the early 1980s.

Beyond the Discount Rate Effect

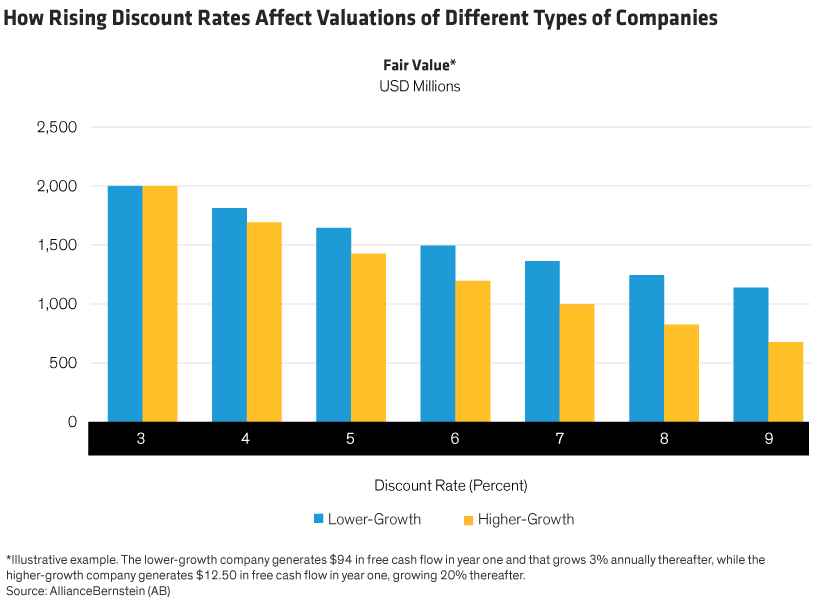

The impact of rate hikes on economic activity remains to be seen. However, the impact on stock prices is already visible, with growth stocks getting hit particularly hard. Most of the declines are a direct function of higher discount rates, a key determinant of equity valuations (Display). The discount rate is a risk-free base rate plus a risk premium (or spread) that varies by the characteristics of the asset being valued. Clearly, the risk-free base rate has risen. The equity risk premium—the amount investors require over the risk-free rate—is harder to observe, but we believe increases have been broadly limited so far.

Behind the technicalities of valuation theory lies an important implication for investors. If equities have fallen primarily because of rising rates, the market may not yet be pricing in growing threats to company fundamentals. Across sectors and industries, companies face higher borrowing costs as rates rise, which may slow economic activity and is also creating currency headwinds as the dollar strengthens. Put differently, we believe many investors have yet to adjust earnings forecasts to reflect this escalating uncertainty, even in sectors where share prices dropped sharply. And prevailing earnings expectations were set in an environment of unusually strong profitability, which still looks unsustainably high (Display).

Untangling Distortions in Businesses and Share Prices

This sets up an epic challenge for investors. To make sense of valuations, we must untangle distorted views of business potential from sustainable, longer-term trends. During the pandemic, demand distortions were widespread—tainting profitability projections ever since. Today, we must establish how underlying trends compare to long-term history for industries and companies. Passive equity funds have no way to discern between companies with sustainable business drivers. Actively managed funds have a unique opportunity to demonstrate skill at identifying companies positioned to withstand stress and deliver fundamental and investment results over time.

Distortions have been fueled by multiple forces. Stock prices were distorted by a flood of money entering equity markets. Company results were distorted by waves of surging demand for goods or services that didn’t affect industries equally or at the same time. Prices for goods were distorted by supply chain bottlenecks.

Fleeting influences should never set equity valuations. Companies generally get rewarded over time for delivering differentiated performance, not for one-off bonanzas. But events playing out over 12–18 months may mislead investors into thinking they are durable. For example, pandemic lockdowns in 2020 caused a surge in demand for home-centric products such as exercise bikes, appliances and home improvement projects.

What did that mean for profitability? In normal times, profitability is often influenced by the sales mix of a company’s “good,” “better” and “best” products. The “best” products command higher value and are more profitable than “good” products. After COVID, strong demand stretched out product lead times and pushed up prices. Meanwhile, rising equity prices bolstered consumer balance sheets and reduced buyer sensitivity to purchase prices, particularly for big ticket items such as housing (Display). The post-COVID price mix was on steroids, with customers frequently forced to buy better or best products, given scarce supply. This often drove margins to record levels, along with valuations, as investors assumed the good times would continue to roll.

Some retailers said they might never offer discounts again. Yet, by mid 2021, demand started to shift from goods to services, such as leisure and travel. Fast forward to 2022, and those retailers that had overestimated demand sustainability needed to clear inventory and were forced to lower prices, which typically hurts margins. And that was before central banks started raising interest rates.

Similar situations unfolded in many sectors, impacting both growthy and mature companies, regardless of their business quality. In many cases, companies with one-time windfalls were priced to assume a permanent step up in growth, in contrast with historical performance. This created an increasingly unattractive risk/reward profile.

Finding Consistent Profitability Amid Uncertainty

Investors are understandably confused by this landscape. But we believe there is a clear prescription for choosing stocks despite the uncertainty.

Avoid companies that show suspiciously strong profitability. Warning signs include unusually strong gross margins and sales growth relative to history, and unusually strong returns on investment.

Instead, identify companies with consistently high return on assets and return on invested capital over longer periods of time. These profitability measures are good signs of quality, especially if a company is reinvesting profits back into the business. We aim to verify that profitability or valuations are high for reasons that can be explained—not because of transitory impacts.

The moral of this story? Beware of companies that are being rewarded for untenable business results. This creates higher risk relative to the potential reward (and vice-versa). In other words, being in the right place at the right time doesn’t warrant a sustainably high multiple. Think of a bank, considering lending to a borrower who just won $1 million in the lottery. That windfall wouldn’t be seen as sustainable annual income for the borrower.

Apply the same principle when evaluating post-COVID corporate performance and valuations. With a disciplined, bottom-up fundamental research process, investors can establish the appropriate context for each company and develop a dispassionate assessment of risk and reward. This is the best way for equity investors to successfully navigate uncertainty ahead as the impacts of central bank tightening become clearer, and position a portfolio for a future recovery.