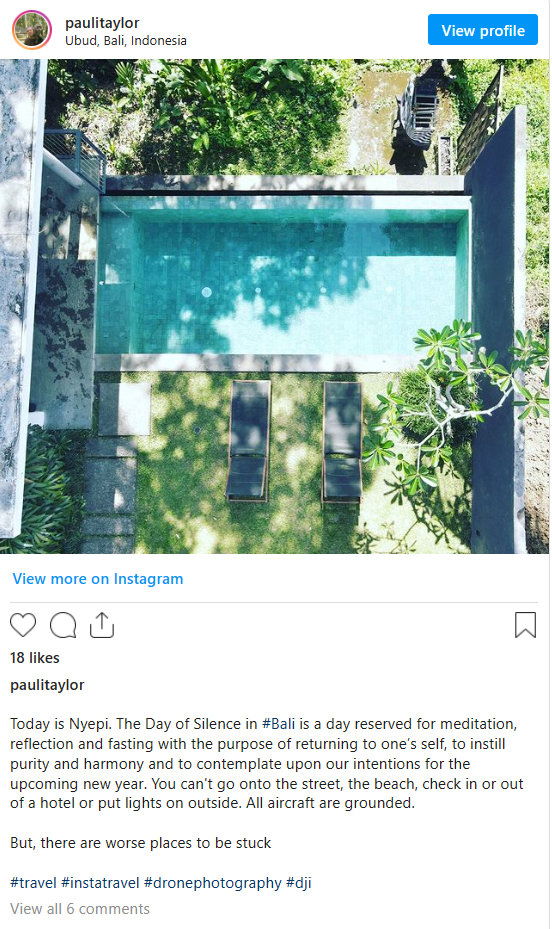

On Wednesday 22nd March I was back in lockdown, confined to a hotel room for 24 hours. Don’t feel sorry for me though, I was in Bali, Indonesia.

On Nyepi day , which is New Year’s day in the Balinese Saka Calendar, the island turns off all lights and sounds, stops traffic, reflects and meditates. You can’t go for a walk, visit the beach, check in or out of a hotel, and the international airport is closed.

Complete silence and serenity reigns over the entire island.

And it got me thinking, do our organisations need a day of silence?

And by an organisational ‘Day of Silence’ I don’t mean meeting free days, which are often just days filled with hours of ‘work about work’ or mind numbing bouts of e-learning. I mean a complete disconnection and meditation on the meaning of work, our purpose, our role within it.

If you’re thinking I’ve inhaled too much frangipani incense, let me present my defence. Less than a third of Americans are engaged with their work, whilst in the UK only 9% feel energised by their work or the workplace.

We are also have a productivity and creativity paradox:

The more investment that is made in technology, worker productivity goes down instead of up.

The more leadership support that is provided the more employee creativity is stifled rather than released.

As a culture, we don’t do very well with silence. We are taught to say our piece as a sign we are engaged. Those that don’t – those that might actually be thinking rather than mouthing off – are often undervalued or even dismissed as blockers. “Maybe we should think about this?” is the hallmark of an indecisive leader.

Few businesses place any value on purposeful thinking – as ‘thinking about stuff’ looks too much like loafing about. We are in a world that sometimes places a higher value on speaking and commenting than on thinking.

We are also obsessive about collaboration when many people are at their most creative during solitary activities like walking, relaxing or bathing, not when stuck in a room with a whiteboard.

Indeed. a study found that “solitude can facilitate creativity–first, by stimulating imaginative involvement in multiple realities and, second, by ‘trying on’ alternative identities, leading, perhaps, to self-transformation.”Essentially just being around other people can keep creative people from thinking new thoughts.

The Value of Introverts

People who like to spend time alone, or who are less comfortable in group situations, are decidedly at odds with today’s team-based organisational culture. The danger is that with a focus on all-out collaboration you miss out on the creativity of introverts.

When I started group facilitation I learned two things very quickly:

- Introverts have some of the best ideas but often don’t feel very comfortable talking openly about them in a group setting.

- Extroverts are only too willing to share their ideas (in fact they rarely shut up about them) but are sometimes reluctant to listen to good ideas proposed by others.

Organisational silence often refers to a collective-level phenomenon of saying or doing very little in response to significant problems that face an organisation. It’s a bad thing. But what if we flipped the concept and became a more meditative organisation?

Perhaps an organisational Day of Silence may hold back the macho high energy leaderist default to doing things, and make them lean – in to the thoughts and wisdom of introverts not just their louder counterparts?

Perhaps we could start thinking about the dysfunctions in our whole system rather than just within our teams?

Perhaps we could empower teams across all levels and silos to think holistically.

Maybe , just maybe, if we did that organisations might move beyond the cycle of start-stop-forget-repeat that we are seemingly locked in.

What could an organisational ‘Day of Silence look like?

As a minimum it would mean an organisational blackout on non-essential work, the work that gets in the way of real work. At its most radical it would follow the Bali model and shut down everything that wasn’t an immediate threat to health.

- It would mean every employee taking time out to think deeply about the dysfunctions in the system and what prevents them from delivering value regardless of the consequences for them.

- It would need to be collective and focus on the needs of the user not the organisation or its regulators.

- It would need absolute commitment by management to firstly allocate one day each year for silence and then 364 days to act on the results regardless of what it means for them.

The cynics would say with those three bullets you’ve answered your own question. That’s why we don’t have an organisational day of silence and never will.

Maybe they are right. However, almost every survey on employee engagement, every report on productivity, every piece on the perilous state of trust in institutions suggests that that it might be, at the very least, worth a try.

Related: Big Consultancy and The Rise of The Non-Expert ‘Experts’