Written by: Margot Crandall-Hollick, Elli Nikolopoulos, Elaine Maag, and C. Eugene Steuerle

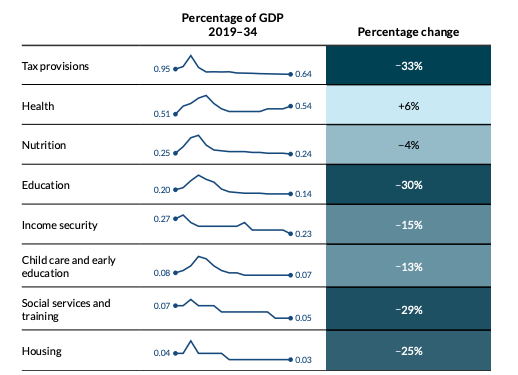

Scheduled percentage change in federal spending on children as a share of GDP, by category, 2019–34, before any budget or tax legislation enacted in 2025. Source: Heather Hahn, et al., Kids Share, 2024.

By the end of 2024, federal spending on children relative to the size of the economy was scheduled to decline under current law (figure 1). Though the US economy is expected to grow, federal investments in children will not keep pace. This decline may be more severe if Congress enacts the spending cuts in the House of Representatives FY2025 budget resolution.

Federal policymakers should instead commit to investing 2.7 percent of GDP in children (the 10-year prepandemic average). Congress could also set a goal to spend 1 percent of GDP on the largest tax provisions that support families—today, the Child Tax Credit (CTC) and the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). Those provisions make up just 0.6 percent of GDP—about half the high-water mark observed in 1960 for the personal exemption for dependents that then was in place but was eliminated in 2017 for recent years.

Here are some more details:

-

Overall federal investments in children as a share of the economy are set to decline by 20 percent compared with spending levels before the pandemic. In 2019, public investments in children were about 2.4 percent of GDP. In 2034, they are projected to be about 1.9 percent, and these numbers are before any legislation in 2025.

-

Tax provisions will see the largest percentage decline, decreasing by more than 30 percent. The main driver of this long-term decline is that major tax benefits for children in place over time—the CTC, EITC, and personal exemption for children—are not tied to economic growth. The maximum CTC does not even increase with inflation. That means its value as a share of GDP tends to decline even faster than that of the EITC and other tax provisions that are adjusted for inflation.

-

Potential cuts to Medicaid in the FY2025 House budget resolution could blunt or even reverse projected increases in health spending and affect children’s long-term health. After federal tax provisions, health is the largest spending category for children, largely reflecting spending under Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. This is the only area projected to see a modest increase (6 percent) between 2019 and 2034, as overall government spending on health care is expected to grow slightly faster than the economy.

-

Declines in education spending are projected to be steep (almost one-third). That calculation is even before any Presidential or Congressional action to eliminate the Department of Education and some of its spending.

-

Spending on child care, social services, and housing is also expected to decline by about one-fifth from pre-pandemic levels. This could leave young children less prepared to enter kindergarten and limit their educational attainment. When these children enter adulthood, they would be more likely to earn lower wages and have worse health outcomes, limiting their own thriving and leading to a less productive economy.

How Policymakers Could Better Support Children and Families

-

Set an annual target for spending on children. Policymakers could set the target of spending 2.7 percent of GDP on children, to match the 10-year average prepandemic levels. Congressional committees could also set specific targets for programs in their purview. For example, the House Ways and Means and Senate Finance Committees could aim to invest 1 percent of GDP on tax benefits for children every year.

-

Ensure all tax benefits for children at least grow with inflation. Congress is considering extending the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act’s expanded CTC, which will expire at the end of this year. However, the CTC has not been adjusted annually for inflation, so its value as a share of GDP has fallen even faster than that of the EITC. To ensure the credit keeps pace with rising costs, policymakers could increase the maximum credit per child from $2,000 to $2,500 to account for recent inflation since 2017 and then index the credit for inflation going forward. The current House bill sets the credit at $2,500 for a few years, then at $2,000 for 2029, and only then adjusts for inflation. Policymakers could also modify the credit’s phase-in to ensure working families can access more of the full credit.

-

Continue investing in safety net programs with proven short- and long-term benefits for children. These investments pay off not only for individual children but also by increasing the productivity of the US economy.

Related: What’s Really Driving Markets? Long-Term Forces Outweigh Trump’s Tariff Moves