Written by: Eugene Steuerle

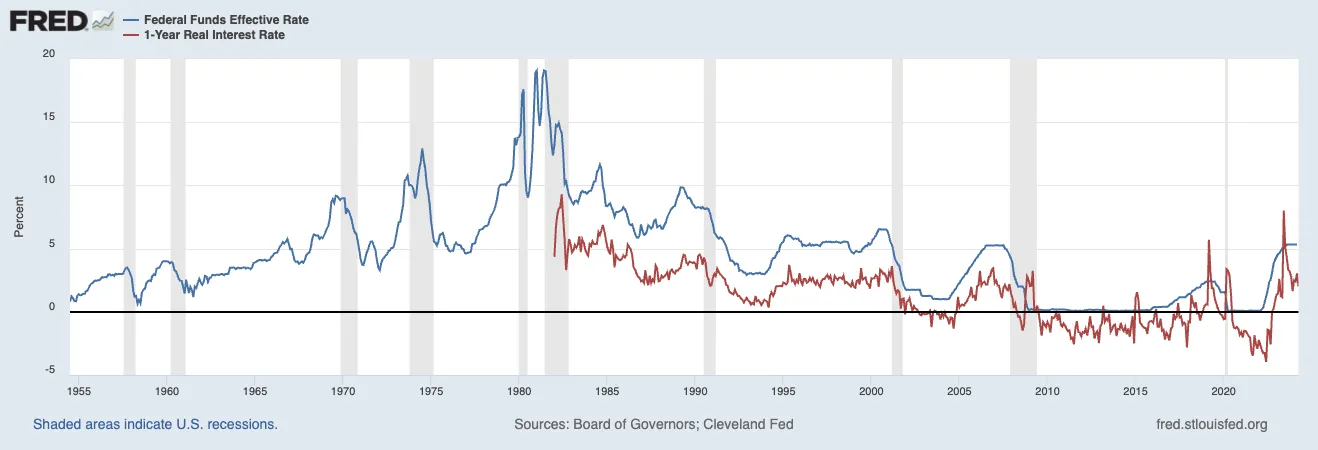

Because inflation remains high, the Federal Reserve (Fed) has not lowered its key “federal funds” interest rate, which has remained above 5 percent since May 2023 (see graph). While this rate remains high by 21st century experience, it’s below the average rate from 1955 to 2000. Even more exceptional, the real interest rate—the nominal rate less inflation—has been close to zero for much of this century. While it has jumped recently, the Congressional Budget Office, reflecting a Blue-Chip consensus within the financial markets, projects that it will soon return toward zero, at least for a few years.

These data raise the question: what should the rate be? And which rate?

I don’t have a precise answer, partly because reckless fiscal policy, with large deficits in good times and bad, has weakened this nation’s ability to react to economic swings. That puts a lot of pressure on monetary authorities. Nonetheless, negative real borrowing costs, which I show below to be lower than the real interest rate, cause real damage to the economy. Those concerns limit how much the Fed should reduce the interest rate when the inflation rate falls.

In a 1985 book, I delved into why inflation led to economic stagnation. Dissatisfied with the explanations prevailing then and now, I focused more on the interaction of monetary and fiscal policy within capital markets than on labor markets. Consider a scenario where inflation spikes from 0 percent to 5 percent for a simple illustration of why capital markets face distortions that significantly affect decision-making. In this case, a wage of $100 could be devalued to around $95, a distortion of 5 percent. However, if the interest rate jumps from 2 percent to 7 percent due to the additional inflation, the real interest rate would be overstated by a staggering 250 percent.

With inflation, investors compare nominal bond rates to dividend rates, sometimes ignoring how a company’s underlying assets increase over time with inflation. Pension actuaries make guesses about how much future pensioner liabilities will continue to decline because of inflation and how asset values in stock and bond markets will adjust. The home mortgage market becomes particularly distorted for reasons I will not fully engage here, but you can easily see how home sales today stagnate as existing owners hang on low-interest rate loans by not selling their houses and moving.

I noted that the cost of borrowing is lower than the interest rate. Business and higher-income borrowers get to deduct both the inflationary and real components of the interest rate in calculating their income. Accordingly, their financial and tax income statements overstate their real borrowing costs, and the tax system grants them a tax subsidy per dollar of the loan equal to the inflation rate times their marginal tax rate. A similar tax penalty would apply to lenders, except that nontaxable entities do much of the lending. When loans go to owners whose assets grow in value but remain unsold for a long time—commercial real estate stands out as a prime example—the subsidy for borrowing becomes larger still. In the example above, the business deducts 7 percentage points of the loan while often deferring or excluding any net return on newly purchased assets. Finally, bankruptcy laws further protect borrowers—an item I failed to examine in the earlier book—so that the expected cost of borrowing is even lower.

Very low and negative real interest rates have likely been one cause of the wealth bubble in stocks, homes, and other assets we’ve been in over the last few decades.

Those low rates further promote wealth inequality, as wealthy individuals and businesses, including private equity and other partnerships, leverage up their purchases of assets as long as they provide a less negative return than the negative cost of borrowing. Less wealthy individuals do borrow, but they get smaller or no tax subsidies for purchasing assets because they are in a low or zero tax bracket. They are also more likely to use debt, as with second mortgages and credit cards, to finance consumption, not asset purchases.

Low—and middle-income households who try to save through savings accounts earn negative returns when the real interest rate is below zero. Today’s generation of young adults under age 50 has yet to experience any significant real return from this traditional form of saving. They and their children know more about getting frequent flyer miles from amounts they borrow on their credit cards.

Zero and negative interest rates have also allowed Congress to continually increase the nation’s debt levels. If it costs nothing for the government to borrow, Congress finds it easy to conclude that deficits don’t matter.

Only recently has the real interest rate returned to more normal territory. If inflation declines, the Fed will undoubtedly reduce nominal interest rates. I question how far it should go in re-engaging the problems created by negative or near-zero real interest rates.

Related: Why Annuities Belong in Clients’ Retirement Income Plans