Written by: Tom Nakamura | AGF

Bond investors have been laser-focused on the impact of rising rates this year, and understandably so. In March, the U.S. Federal Reserve – the most influential central bank in the world – made good on months of speculation when it raised its benchmark federal funds rate from zero to 0.25%, and recent remarks from Fed officials suggest that they expect more to come. The Fed hike followed by two weeks a similar move by the Bank of Canada (BoC), which raised its benchmark rate by 25 basis points (bps), to 0.50% at the time, only to follow that up with another 50-basis point hike on April 13. In response, the yield curves in North American bond markets have flattened dramatically. The spread between 10- and two-year Canada benchmark bond yields compressed from the start of the year to now, according to Bloomberg data. Meanwhile, the two- and 10-year spread for U.S. Treasuries has dropped from around 100 bps a year ago to less than 25 bps today, and parts of the yield curve briefly inverted at the start of April.

Investors, of course, have good reason to pay attention to these developments. Driven by central bank efforts to combat above-trend inflation, yield curve flattening has rocked North American bond and equity markets, and in the economy, it has raised the spectre of slowing growth and perhaps even recession. Yet when we expand our view, we see that the pattern of tighter monetary policy and flattened yield curves is not so uniform, even across developed economies. In fact, in two important markets – the European Union and Japan – central banks have yet to follow the U.S., Canada and other countries towards policy normalization, and they might not do so for quite some time.

For the European Central Bank (ECB), the proximate driver of continuing accommodative monetary policy is the war in Ukraine. That conflict, which is about to enter its third month, presents a clear risk to economic growth in the European Union, and it will likely deter the ECB from being too aggressive in terms of raising rates off from zero or otherwise normalizing its policy stance. It also presents the central bank with something of a conundrum, since downside concerns about growth are being confronted by upside pressure on inflation, especially through energy and food.

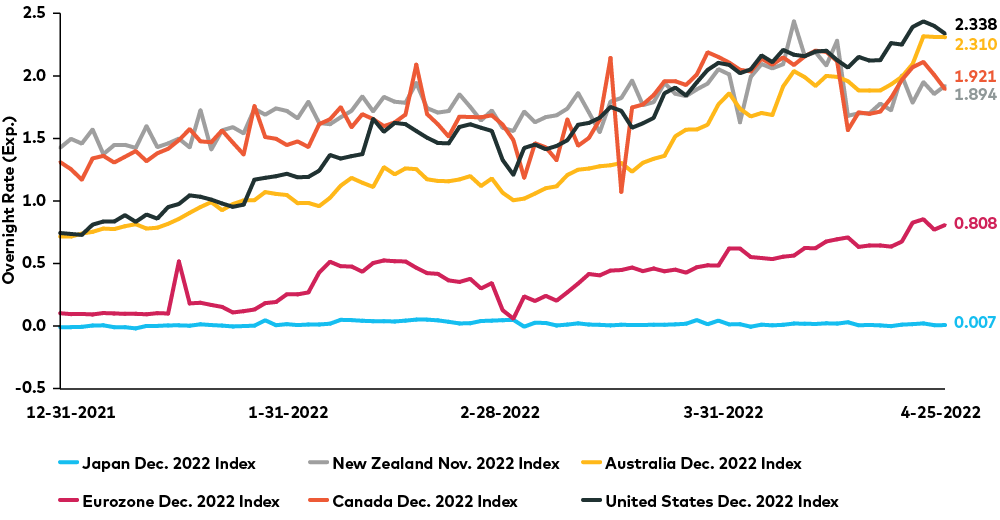

On balance, however, it seems clear that the ECB will err on the side of caution. Markets are pricing in a much more modest benchmark rate increase for Europe to the end of 2022, compared to expectations for the U.S., Canada, Australia and New Zealand, according to Bloomberg data. (Notably, the last two countries in that list are among those that are furthest along in their emergence from the COVID-19 environment.)

Central Bank Interest Rate Divergence: What’s Priced In?

Source: Bloomberg L.P. as of April 26, 2022

Perhaps even more noteworthy, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) is not expected to raise rates at all this year. The Japanese central bank appears to be steadfast in its commitment to yield curve control (achieved through the aggressive purchase of bonds) and to ultra-loose monetary policy, even as rising yields globally have sparked a sharp devaluation of the yen against the U.S. dollar. Policymakers still have plenty of bandwidth for monetary stimulus. Inflation in Japan is running well below the BoJ’s notional 2% target, according to Bloomberg data, although disruption in energy markets (brought on by the Russia-Ukraine crisis) and a devalued currency is putting upward pressure on prices.

The effect of this policy divergence is clear in these countries’ respective yield curves: while they are flattening for U.S. and Canadian government bonds, they remain relatively steep (and more stable in their steepness) for European and Japanese bonds.

This discrepancy may persist for some time. For Europe, war in Ukraine is undoubtedly a major factor in the ECB’s accommodative stance, and it could be a short-term crisis, but substantial friction in energy and agricultural markets is likely to survive any kind of resolution with Russia. It’s worth remembering, too, that European monetary policy was already diverging from its North American counterparts before the Russia-Ukraine crisis; if that conflict lasts or intensifies, the gap could become even wider. And because of demographic factors – Europe has the world’s second oldest population, according to the United Nations population division – the longer-term growth outlook there already lags the U.S., suggesting that monetary policy will likely be looser over the long term anyway. That applies even more to Japan, which has the world’s oldest population (28% over the age of 65) and has not achieved 2%-plus GDP growth in nearly a decade, according to the World Bank.

For investors, this divergence presents a window of opportunity to consider bond yields a little more thoughtfully than simply focusing on the U.S. and Canada. With rates rising globally, there has been no place to hide from declining bond prices, but the declines have been less ravaging in Europe and Japan than elsewhere. And going forward, investors may capitalize on policy divergence by gaining exposure to different parts of the yield curve in different countries. For example, it might be that Japan’s yield curve is “too steep” right now and the U.S. curve is “too flat,” in which case an investor may seek exposures to longer-duration Japan bonds and shorter-duration Treasuries. Or, to the extent that lower rates are supportive of stocks, suppressed relative yields in Europe and Japan present potential opportunities in equities.

In short, as bad as bond markets have been in 2022, there are opportunities to be had for investors with the flexibility to look beyond more familiar countries. Monetary policy divergence between the U.S./Canada and Europe/Japan illustrates the potential benefits of approaching fixed income from a global perspective.

Related: Why Some Emerging Markets are Leading the Pack and Raising Rates

The views expressed in this blog are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the opinions of AGF, its subsidiaries or any of its affiliated companies, funds, or investment strategies.

The commentaries contained herein are provided as a general source of information based on information available as of April 27, 2022 and are not intended to be comprehensive investment advice applicable to the circumstances of the individual. Every effort has been made to ensure accuracy in these commentaries at the time of publication, however, accuracy cannot be guaranteed. Market conditions may change and AGF Investments accepts no responsibility for individual investment decisions arising from the use or reliance on the information contained here.

“Bloomberg®” is a service mark of Bloomberg Finance L.P. and its affiliates, including Bloomberg Index Services Limited (“BISL”) (collectively, “Bloomberg”) and has been licensed for use for certain purposes by AGF Management Limited and its subsidiaries. Bloomberg is not affiliated with AGF Management Limited or its subsidiaries, and Bloomberg does not approve, endorse, review or recommend any products of AGF Management Limited or its subsidiaries. Bloomberg does not guarantee the timeliness, accurateness, or completeness, of any data or information relating to any products of AGF Management Limited or its subsidiaries.

AGF Investments is a group of wholly owned subsidiaries of AGF Management Limited, a Canadian reporting issuer. The subsidiaries included in AGF Investments are AGF Investments Inc. (AGFI), AGF Investments America Inc. (AGFA), AGF Investments LLC (AGFUS) and AGF International Advisors Company Limited (AGFIA). AGFA and AGFUS are registered advisors in the U.S. AGFI is registered as a portfolio manager across Canadian securities commissions. AGFIA is regulated by the Central Bank of Ireland and registered with the Australian Securities & Investments Commission. The subsidiaries that form AGF Investments manage a variety of mandates comprised of equity, fixed income and balanced assets.