Written by: Patrick O'Connell, John Huang, and Erin Bigley

As environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors help contribute to—or detract from—security returns, it makes sense for active investors to integrate them into security selection. But there’s a wide disparity in the materiality of ESG factors across investment sectors and markets. In our view, understanding this dynamic is the key to successfully incorporating ESG risks and opportunities into portfolio construction.

For many investors, whether fixed income or equity, the process of integrating ESG factors into their strategies begins with correlating the relevance of each factor to individual industries. At a basic level this shows, for example, that greenhouse gas emissions are a particular risk for mining companies and electric utilities, while customer privacy is a key concern for the healthcare sector.

This is a good starting point but offers an incomplete perspective. We believe a much deeper dive is necessary to fully dimension the materiality of ESG factors for portfolio performance. Investors need to know how a particular factor may affect investment returns for a given sector or market.

Factors Can Have Wide or Narrow Impacts

Factor attribution using historical returns can reveal how ESG factors have contributed to investment returns in the past, whether for a sector or an entire investment universe, in equities or in bonds.

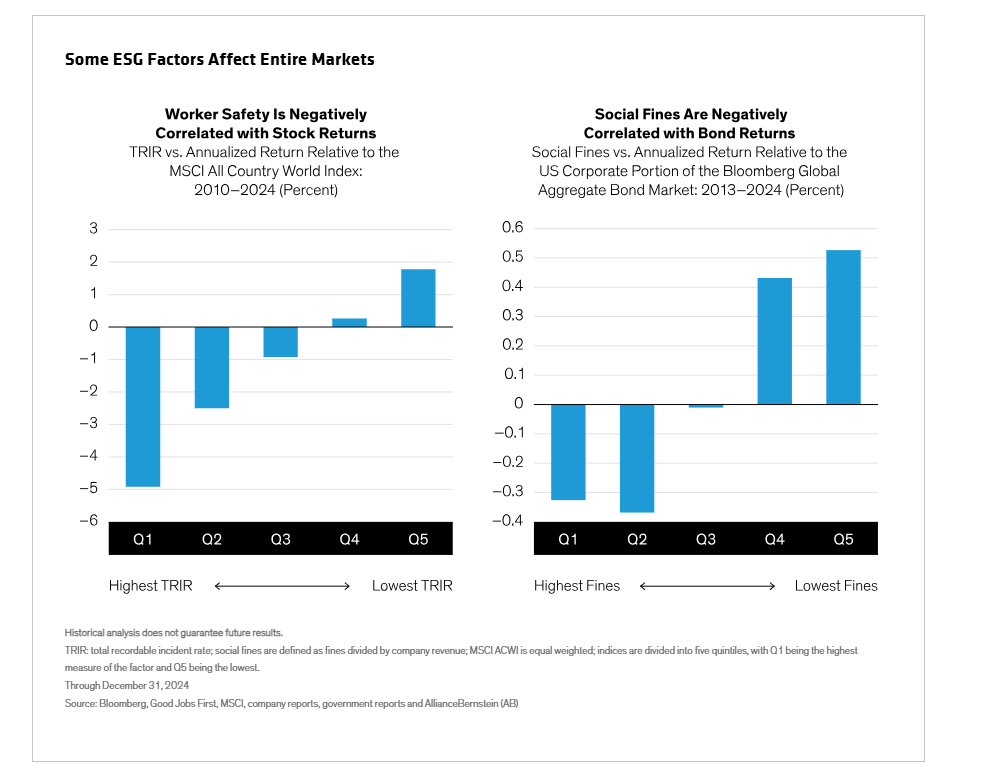

We’ve observed that some factors can be financially material for all companies in a market, regardless of sector. For example, we divided stocks in the MSCI All Country World Index into quintiles according to their total recordable incident rate (TRIR)—the number of workplace injuries or illnesses—then compared their returns relative to the parent index over 14 years (Display, left). The results show that high TRIR consistently underperformed the market and that low TRIR consistently outperformed.

Similarly, in the bond market, “social fines” is a powerful, index-wide factor (Display, right). Social fines are regulatory penalties imposed for nonenvironmental reasons, such as workplace health and safety and anticompetitive practices.

Other ESG factors with broad relevance across investment sectors include CEOs’ length of tenure and employee turnover. For investors wishing to integrate ESG factors into their portfolios, it’s useful, in our view, to know which factors have index-wide applicability.

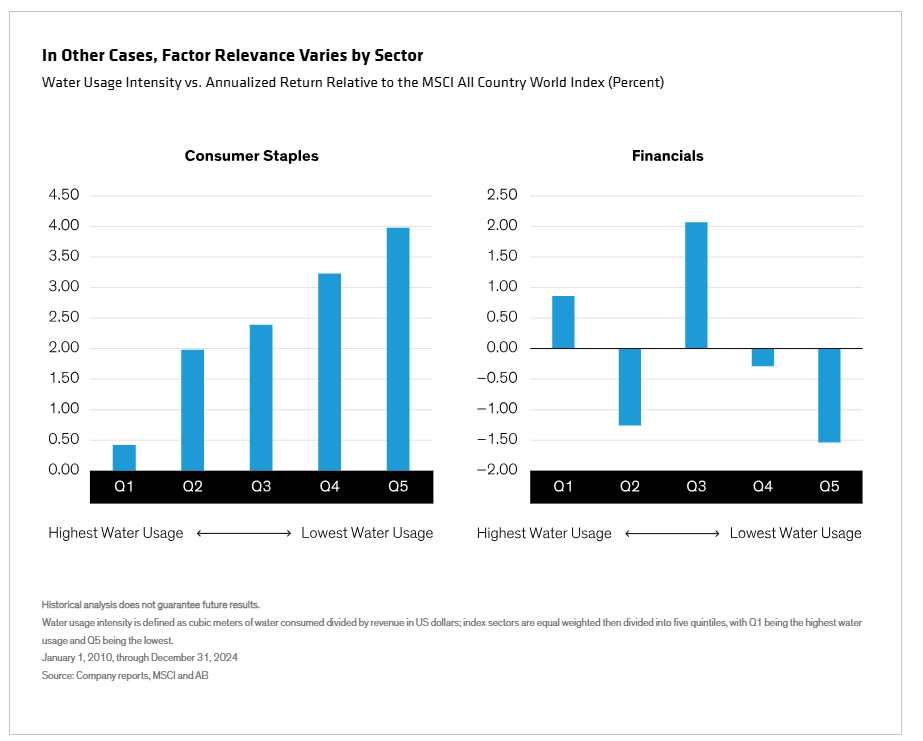

Factor attribution can also reveal which ESG factors are particularly relevant to a specific sector and which have historically shown no financial materiality (Display).

Another advantage of factor attribution is that it can lead to observations that are unexpected and even counterintuitive. We found, for example, that companies with high ESG disclosures broadly performed better than those with low or no disclosures, regardless of whether their ESG practices were good, bad or indifferent. In the case of ESG metrics where there was no significant under- or overperformance relative to the market—CFO tenure and split roles for CEO and chair of the board—companies that disclosed data outperformed companies that didn’t disclose, on average.

Fundamental Research Enhances Insights from Factor Attribution

But factor attribution alone is not enough, in our view; it should complement fundamental research.

Understanding the effect of ESG factors on performance is most valuable in the context of broader research into how well a company is managed. For example, fundamental research can show that a high TRIR affects productivity directly, through lost working hours, and indirectly, by creating a culture in which workers are undermotivated because they don’t feel safe. Additionally, factor attribution works best with long data series, which are not always available, stressing the importance of fundamental research.

Another way fundamental research can help is in measuring ESG factors appropriately to a particular sector, instead of taking the generic approach typically used by many third-party ESG databases. This could mean, for example, measuring carbon emissions in terms of miles per gallon for automakers, per passenger mile for airliners and per ton of cement produced for building-material companies.

And it can tease out the nuances underlying many ESG factors. In the case of the mining sector, for example, fundamental research can focus on tailings dam risk within the more broadly defined factors of water and hazardous materials management (Display).

As this small snapshot of an ESG materiality matrix shows, these insights can be mapped very simply. But it’s the quality of the information behind it that gives the map its value: the understanding of how ESG factors can be financially material across investment sectors, industries and markets. By embedding such knowledge in their securities research and portfolio construction, investors, in our view, may significantly enhance the potential for outperformance.

The authors wish to thank Peter Højsteen-Ljungbeck for his contribution.

Related: Tech Stocks in Turmoil: Where Smart Money Is Moving During the Tariff Storm