Written by: Nick Veronis and Laura Sexton | iCapital Network

Through technology and product innovation, a variety of registered funds make high-quality private equity and credit available to individual investors.

The private markets have been the domain of institutional investors for many decades. In that time, public and private pension funds, foundations, endowments, insurance companies, and family offices have enjoyed the higher returns and diversification benefits of private investments such as private equity, private credit, and private real estate.

Private markets have become a critical source of return generation for portfolios and institutional investors often allocate 15% to 20% to them. A look at annual endowment fund rankings – and their underlying portfolios – demonstrates this. Today, it is almost impossible to place in the top 10 for endowment performance without at least a 15% allocation to private investments. In fact, top-decile performers often have 40% or more of their portfolios allocated to private investments.[1]

A new generation of funds for individual investors

While institutional investors have enjoyed the benefits of private investments, these strategies have historically been inaccessible to most individual investors. The investment minimums required to access these funds directly are typically $5 million or more and, regardless of the minimum, individual investors must meet the Qualified Purchaser (“QP”) standard to invest directly in these funds. In addition, most private fund managers are not set up to administer and process small commitments from individual investors at scale – their infrastructure was created to service institutional LPs making large investments.

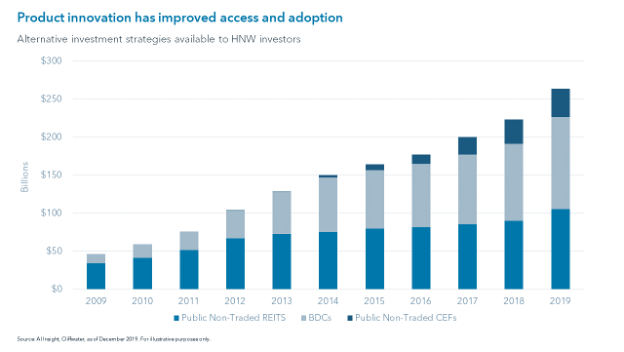

Over the past two decades, however, product innovation has enabled fund managers to bring to market products that make private investments accessible to individual accredited investors and even non-accredited investors. Individuals qualify for accredited investor status with at least $200,000 in annual income (or $300,000 of joint income) or a net worth of $1 million or more. This market encompasses an estimated 13.6 million U.S. households (compared to only 1.5 million QP households) and roughly $73.3 trillion in wealth, representing more than 75% of the wealth in America.[2]

As with the evolution of the mutual fund industry, the evolution of these individual investor-focused private investment funds has had its share of hiccups. The first generation of private investment funds designed for individual investors delivered inconsistent performance – fund managers tended to be smaller and less experienced. Funds often experienced liquidity mismatch issues, fees tended to be higher and less aligned with shareholders, distributions were paid out of offering proceeds, leverage was utilized improperly, and underlying market-like beta was hidden behind the notion of a fund being “non-traded.” These products have evolved, however, and large, established private investment managers have entered the space, bringing with them institutional style pricing, structure, transparency, and education. As such, individual investors now have an opportunity to take advantage of the return and diversification potential of private investments through high-quality fund managers that were inaccessible to them for decades.

Fund managers provide access to private investments through registered fund products, which are those that are registered with the SEC under the provisions of the Investment Company Act of 1940. In addition to providing access to once inaccessible investments and strategies, benefits of these ’40 Act fund structures include more stringent reporting requirements, lower investment minimums, leverage limits, simpler tax reporting requirements (1099 vs. K-1), and independent boards designed to represent shareholders’ interests. The most common registered fund structures include interval and tender offer funds, BDCs, and REITs.

Interval and Tender Offer Funds

Often considered the most flexible investment structure, interval and tender offer funds can own a variety of investments with minimal limits on the percentage of assets in private investments (other than having enough liquidity to cover redemptions). While both types of funds have a wide investment directive, interval funds are mandated to offer a minimum of 5% liquidity on at least a quarterly basis with, typically, a one-year lockup of invested capital. Tender offer funds generally offer similar liquidity. During times of market stress or dislocation, however, the board may decline to make a tender offer if it believes that such an action is not in the best interest of all shareholders. For example, the board may find that to honor the tender offer, the fund would have to sell assets at distressed prices significantly below their true market value and could decline to allow any tenders during that period. While these instances tend to be very rare, they highlight the responsibilities of the board toward all shareholders, and not just those looking to tender shares for repurchase in a possible “fire sale” situation.

Established firms that offer interval and tender offer funds today include Hamilton Lane, Partners Group, KKR, Carlyle Group, Pantheon, and StepStone. The interval fund and tender offer fund markets today represent more than $30 billion and $28 billion in assets under management, respectively.[1]

BDCs and REITs

Business development companies (BDCs) are another, more established structure that asset managers employ to make private market investments, particularly private credit, available to individuals. BDCs, which can be public, private, or non-traded, are closed-end companies that typically make loans to middle market companies. This industry represents nearly $120 billion in assets, up significantly from just over $20 billion in 2010.

Key players in the BDC market include large, experienced private credit managers like Golub Capital, Ares Capital, Nuveen Churchill, and TPG. The majority of assets in the BDC market are in the public space, with over 50 traded BDCs and $80 billion in AUM. Private BDCs, which do not register with the SEC, represent roughly $30 billion. The first non-traded BDC was introduced in 2009 by FS Investments (formerly Franklin Square). Non-traded BDC AUM increased to a peak of $25 billion in 2017 but has subsequently declined to roughly $10 billion as of Q3, 2020 with fewer funds in the market and the listing of several former funds over the last few years. However, the industry is poised for a rebound with several new managers entering the space, including Blackstone.[2]

To provide access to the private real estate market, firms are increasingly offering publicly listed, non-traded REITs. A public, non-traded REIT is required to register with the SEC, although, unlike publicly listed REITs, shares are not traded on a national stock exchange. This allows managers to focus on long-term objectives instead of shorter-term price changes and quarterly earnings. Non-traded REITs tend to have lower minimums than private REITs or other private real estate funds.

Non-traded REITs fall into one of two categories: perpetual life or NAV REITs, which are open-ended, report a NAV on a regular basis, and allow for periodic repurchases, or lifecycle REITs, which are offered through an IPO and have limited to no repurchase options and a defined lifespan that ends with a liquidity event. Earlier iterations of the non-traded REIT industry were focused more on lifecycle REITs, although recently the industry has become much more focused on perpetual life funds which are most similar to institutional style real estate offerings.

While the non-traded REIT industry once primarily comprised smaller, less well-known real estate firms, established firms like Blackstone, Starwood Capital, Jones Lang LaSalle, and Hines now offer them. The engagement of these firms, along with the transparency and more favorable fee structures they have introduced, has helped bring this category to over $100 billion in AUM, more than double its size a decade ago.[3]

Consider the risks

As with all investments, it is important to approach private investments within a registered fund structure in a balanced manner and consider not only the benefits but also the risks. For registered funds that invest in private investments, risks include, among others, the potential for a liquidity mismatch, the wide dispersion of returns between top and bottom quartile returns, the “cash drag” which is the impact of the cash required to be held to meet liquidity needs on returns, commodity risk, leverage risk, and derivatives risk. Additionally, manager selection and proper due diligence are critical to investing successfully in the private capital markets, where the difference between top- and bottom-performing managers can be significant.[4]

Perhaps the most critical concept for advisors and their clients to bear in mind when considering ’40 Act funds that invest in private companies is that, regardless of the liquidity terms, these are fundamentally longer-term holdings and should be viewed as such in a broader portfolio. Private equity firms generate an illiquidity premium through their ability to collaborate with the management teams of their portfolio companies to execute value creation plans that require three to five years (or longer) to realize. These strategies may include expansion into new markets, selective consolidation of a fragmented sector through add-on acquisitions, efficiency improvements/cost reduction, the sale of non-core assets, and/or professionalization of senior management teams. These plans take time. Put differently, one of private equity’s main advantages, particularly over public companies which must deal with the pressures of quarterly earnings and “short-termism,” lies in thinking and acting with a long-term time horizon in mind. It is essential that individual investors have realistic timing expectations regarding liquidity.

Allocations to private market strategies poised to grow

There has been an evolution in the public equity markets over the past 25 years that has resulted in fewer listed companies that are significantly older, on average, than they used to be. In the private markets, meanwhile, investors can access vibrant companies that still have the potential for rapid growth ahead of them. While private market strategies were historically off limits to individual investors, accredited and, in some cases, even non-accredited investors today can add private market exposure through fund structures tailored to their needs and managed by experienced private fund managers with strong track records. Over time, these private market strategies are likely to become a fixture in the portfolios of high-net-worth investors.

Related:

[1] Source: Cambridge Assocates, “Life is Better After 40,” November 2019.

[2] Source: DQYDJ, “How Many Accredited Investors Are There in America?” October 2020.

[3] Source: AI Insight and Tender Offer Funds.

[4] Sources: FS Investments and AI Insight.

[5] Source: AI Insight, AI Insight Public Non-Traded Industry Insights, Q3, 2020.

[6] Source: Preqin, Quarterly Update Private Equity & Venture Capital, Q1 2020.