Written by: Eugene Steuerle

As tempting as it is to attribute every good or bad turn in financial markets to the actions of a president, with such discussions divert attention from the longer-term and more significant changes taking place. Most of at people observe today in the bond and mortgage market—and, by implication, the stock market—likely reflects a return to normalcy after the ending of a prolonged, unusual, yet eventually unsustainable period of declining nominal (before-inflation) and real (after-inflation) interest rates and exceptionally high increases in asset prices.

Starting with the nominal interest rate, it has fallen dramatically since the early 1980s. For instance, in the 30-year fixed mortgage market, the rate reached an extraordinarily low 3.15 percent in 2021 (see chart above).

Correspondingly, the interest cost on federal debt as a percentage of GDP was lower in 2021 than in any year since 1976, even as federal debt itself as a share of GDP quadrupled. However, in 2024, just three years later, the ratio of federal interest costs to GDP nearly doubled, as both nominal interest rates and the total amount of debt rose significantly. Soon, they are projected to reach an all-time high.

What complicates this picture is the difference between what I’ll call the cash flow economy and the real economy, though they interact. Mortgages, for instance, are offered mainly based on whether a person’s cash flow—for most people, from wages—is adequate to cover the initial mortgage payments. To obtain a mortgage, it doesn’t matter whether inflation is expected to reduce the outstanding debt's real value or increase the house's nominal value.

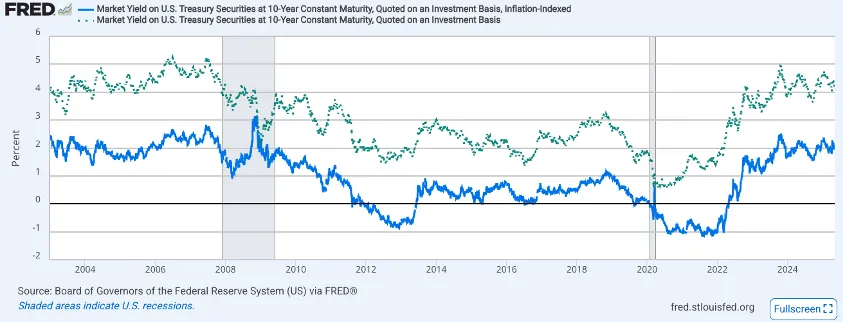

Meanwhile, without even accounting for tax deductions and bankruptcy protections for borrowers, the real cost of borrowing in the U.S. and most developed nations has been below 1 percent or even negative for much of this century, particularly in the years following the Great Recession. When measuring the real cost of federal debt, that rate—not the nominal rate—is the most significant.

Since late 2023, the real return on U.S. Treasury securities with a 10-year constant maturity, adjusted for inflation, has hovered around 2.0 percent, while the nominal rate is just above 4.0 percent. The breakeven inflation rate (the difference between the two) has mainly ranged between 2.2 and 2.4 percent. The real rate on shorter-term securities has been even lower (see chart below).

Except for a few daily incidents, why hasn’t tariff policy so far had much effect on these rates? No one quite knows. Perhaps investors believe that the tariffs will be temporary or that the Federal Reserve will intervene enough to limit the change. Or demand by big banking and governmental investors has held steady.

Regardless, the most significant change in the bond and mortgage market has been a return to a notably positive real rate of interest. This increase began towards the end of the COVID-19 crisis in mid-2022 and reached its current level well before President Donald Trump's second term started.

In an early 2019 Journal of Business research article and a late 2022 Hill article, I noted that a long-term wealth bubble that began around 1990 was likely to be popping, mainly due to an end to these interest rate declines. I defined the bubbling process as deriving from a growth rate in the value of all household assets, ranging from stock to real estate, that significantly exceeded the growth in national income. Despite some modest air seeping out of that bubble since 2021, each $100,000 of household and nonprofit wealth in the U.S. today would still be worth only about $64,000 if the ratio of the market value of wealth to income were to drop to more “normal” 1946 to 1990 average.

If that bubble does not pop, the rate of return on assets will be significantly lower. I am not alone in my concerns. See, for instance, Robert Schiller’s comments on high stock market valuations or the Goldman Sachs projection in late 2024 of only about a 1 percent real rate of return on the S&P 500 over the next decade. That is one percentage point below the 2 percent real rate of return available on a secure 10-year Treasury security.

Those who now favor a return to the abnormally low interest rates may need to consider some of its past implications for both our economy and our governing:

-

Those very low real interest rates likely contributed to the growth in wealth inequality by heavily subsidizing leveraged asset purchases primarily by individuals with considerable wealth.

-

The decline in nominal interest rates over the decades, along with negative real interest rates for much of this century, allowed elected officials to act like Santa Claus when increasing spending or cutting taxes, helping to create our current fiscal bind.

-

Low and negative borrowing costs subsidize unproductive investments that benefit the investor but harm society.

In sum, a return to normalcy in debt and asset markets may be positive in the long run. However, I said neither that the transition would be easy nor that the best way to get there would be to engender a worldwide recession through careless tariff or fiscal policymaking.

Related: Why Everyone’s Wearing Birkenstock—and Why Its Revenues Just Soared