Written by: Adriaan du Toit

Slow vaccine rollouts threaten to take a sizable human toll and create deep, lasting economic scars across emerging markets (EM). The economic impact could be big enough to hurt EM’s post-pandemic growth premium—the difference between the GDP growth rate of EM and developed markets (DM). While vaccinations should accelerate in the second half of 2021, diverging vaccination trends will have wide-ranging effects on public health and economies. As a result, not all EM countries will suffer equally.

What’s more, three pillars of the global economic recovery—infrastructure-focused fiscal expansion among DMs, the transition to greener economies, and early indications of improving trade conditions—could provide a powerful springboard for those EMs less scarred by the pandemic.

Here’s how emerging economies are shaping up under the strain of COVID-19.

Slow Vaccination Trends Scar Emerging Economies

Productivity sets the boundaries for a country’s sustainable debt. That makes assessing the risk of long-lasting, pandemic-driven damage to productivity and potential growth—that is, economic scarring—critical for sovereign EM credit analysis.

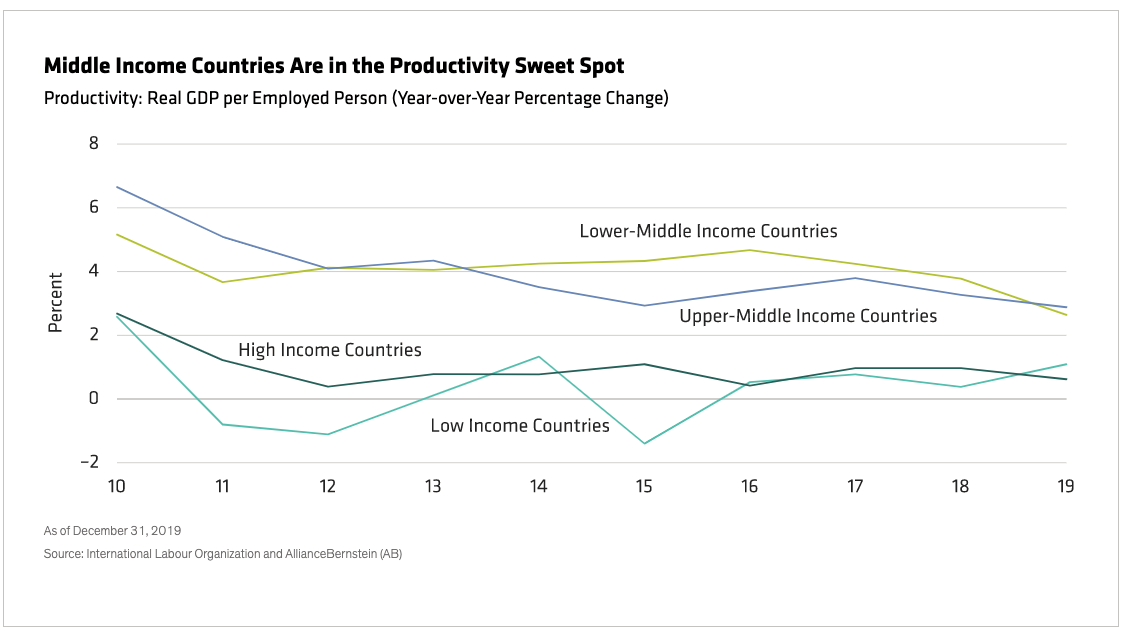

Both low- and high-income countries recorded average productivity growth below 1% over the past decade, while countries in the middle of the income distribution saw productivity growth of around 4% (Display 1). Most EMs that are active in international bond markets are in the middle of the income distribution, where productivity growth is high.

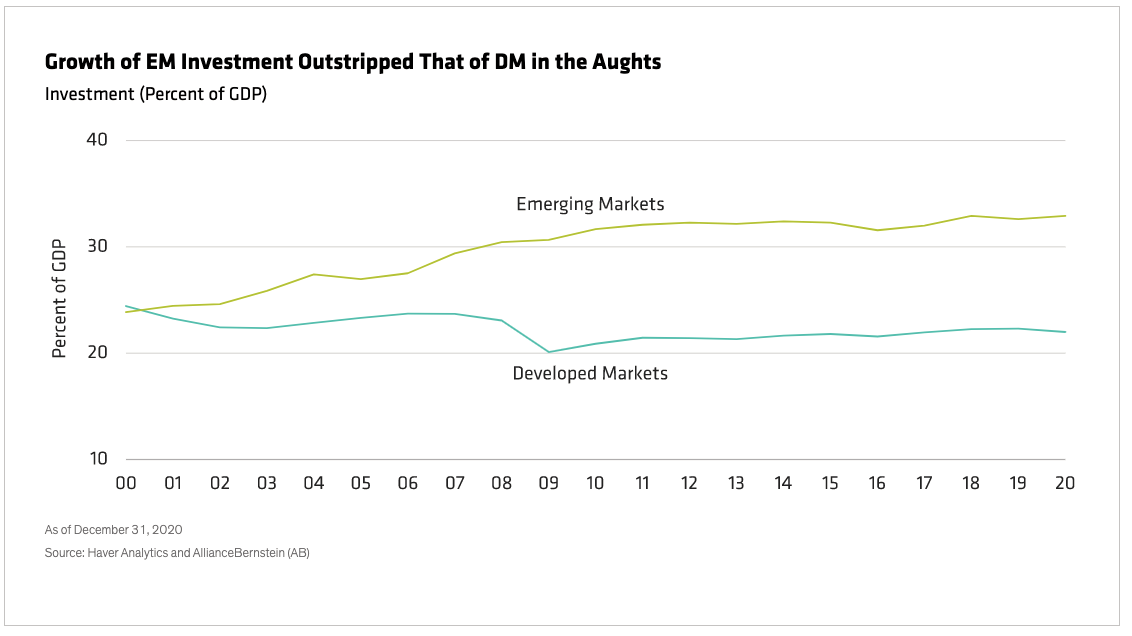

But lower investment (and slower innovation) would threaten EM’s position in the productivity sweet spot. EM investment as a share of GDP outstripped DM investment from 2001 through the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008 and 2009 (Display 2). More recently, EM’s relatively high investment ratio was driven mostly by buoyant investment in Asia and the Middle East; in contrast, investment ratios in emerging Europe, Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa were on par with DM investment ratios.

Rising debt and sticky social spending—which rose during the pandemic—could further curb the EM investment ratio, cut productivity and curtail potential economic growth. Already EM’s growth premium over DM’s has narrowed over the past decade. This trend could persist if economic scarring is widespread.

Green Growth Shoots Could Provide Lift

Thankfully, three encouraging global developments could provide lift to some emerging economies.

First, public infrastructure investment in DM appears to be shifting into high gear. With the multiplier effect of public investment greater than for other forms of government spending, and with borrowing costs near record lows, public-led infrastructure investment in DM—and EM—could form the foundation of the global economic recovery.

Second, infrastructure investment is becoming greener. That points to strong demand for a wide range of commodities and strong tailwinds for commodity-producing EMs. A broad range of EMs are also starting to prioritize sustainable infrastructure investment, as shown by increased issuance of green bonds and other ESG-linked structures. It could take longer for this investment trend to take off and to yield positive results in EM, but a gale of creative destruction could reset potential growth.

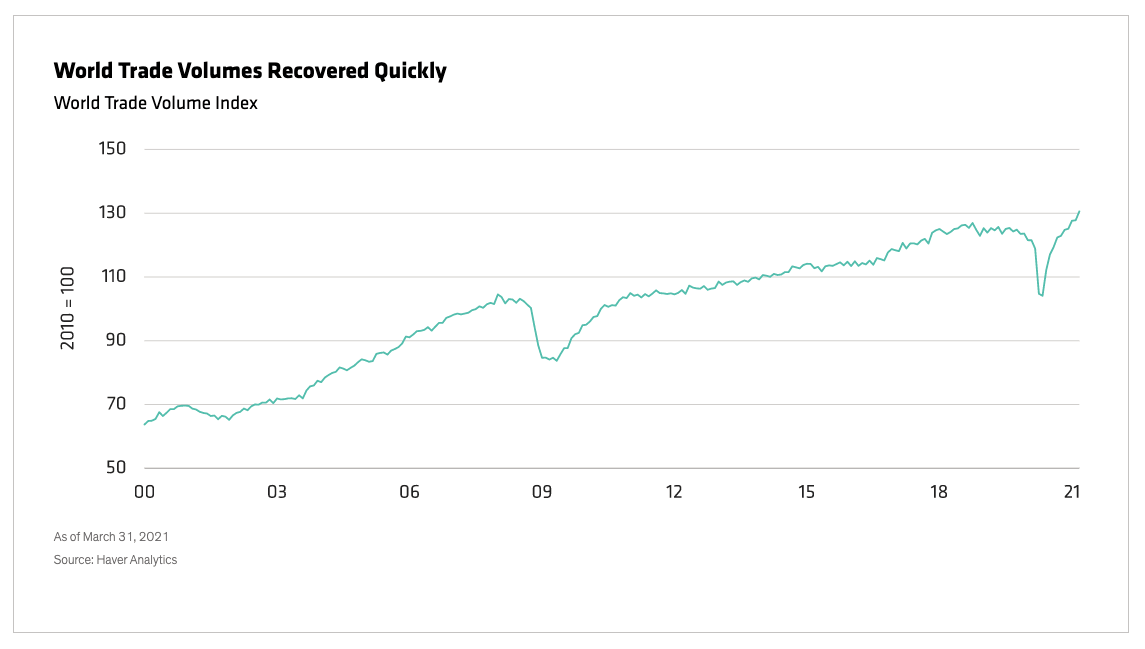

Third, world trade may be looking up. Growth in world trade volumes decelerated after the GFC, slowed to a standstill in 2019 and recovered rapidly since the pandemic’s onset (Display 3). It may now be at a crossroads. We think sustainable infrastructure in conjunction with the prospect of improved multilateralism could create a more constructive trend in post-pandemic trade, which would be positive for EM. Even relations between the US and China likely bottomed already, though the long-term outlook for the relationship between these superpowers remains clouded.

EM Policymaking: It’s Time to Shine

The COVID-19 pandemic has been universally devastating, with some EMs at risk of long-lasting damage. The depletion of fiscal buffers, the disruption to labor markets and the risk of lower potential economic growth leave many EM policymakers and politicians in a fix.

For now, EMs can continue to ride the coattails of robust commodity prices, new Special Drawing Rights from the International Monetary Fund and easy global financial conditions. But these supportive factors might fade—or even reverse—over the next year or two.

The prospect of tighter DM financial conditions is a hurdle for EM. But in our view, what’s potentially more important for the medium-term investment outlook is economic scarring. That’s why, as the health crisis subsides, the quality of macroeconomic policymaking could become a more critical differentiator among EM countries.

Countries with strong or improving policymaking track records, such as Chile, Egypt, Russia and South Africa, could be well placed to take advantage of the post-pandemic environment. These countries may emerge from the pandemic relatively unscathed and may even bounce back forcefully—particularly where policymakers and politicians are willing and able to embrace more sustainable growth models.