Written by: PGIM

Following 2022’s “blow-out” year for many trend- and macro-based strategies, 2023 was a very different story – with generally poor performance, not just relative to 2022 but also relative to the longer-term historical track-record. Economists’ forecasts in late 2022 were for a dismal 2023. Bloomberg’s consensus predictions for US real GDP growth were just 0.3% with 3.6% inflation. Little surprise, then, consensus expectation put the likelihood of a 2023 recession at 65%, the highest recorded response since Bloomberg started its surveys in 2008, barring the few episodes when the economy had actually been in recession.

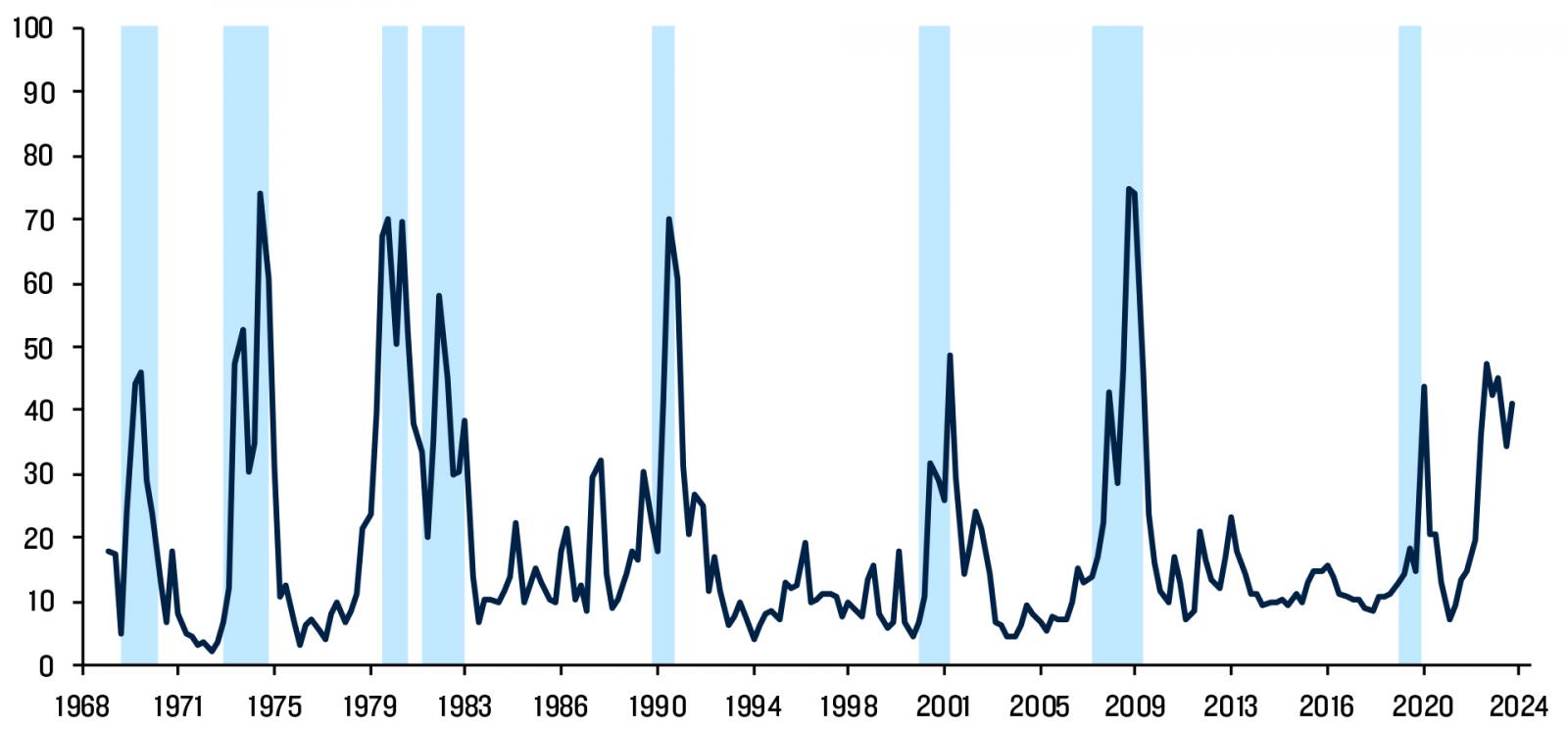

For a better feel for how rare such gloomy forecasts are, consider the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia’s “Anxious Index” which shows there have been very few occasions over the past 55 years when economists were as worried about a recession as they were in late 2022. And very few when they were wrong. Historically, when the Anxious Index is above 45, the economy generally enters recession. But not this time: the consensus forecast today is for real GDP growth of 2.4% for 2023 – or eight times higher than what was expected a year ago.

FIGURE 1: THE ANXIOUS INDEX IN THE UNITED STATES*

One-quarter-ahead probability of a decline in real GDP

Enlarge image

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, as of 13th November 2023.

* The Anxious Index is based on the Survey of Professional Forecasters, carried out by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, showing respondents’ expectations of a decline in real GDP occurring over the next quarter. The chart covers the period 1969:Q1 to 2023:Q4. NBER recessions are shown as blue bars.

WHY DID ECONOMISTS PREDICT A RECESSION AND WHY WERE THEY WRONG?

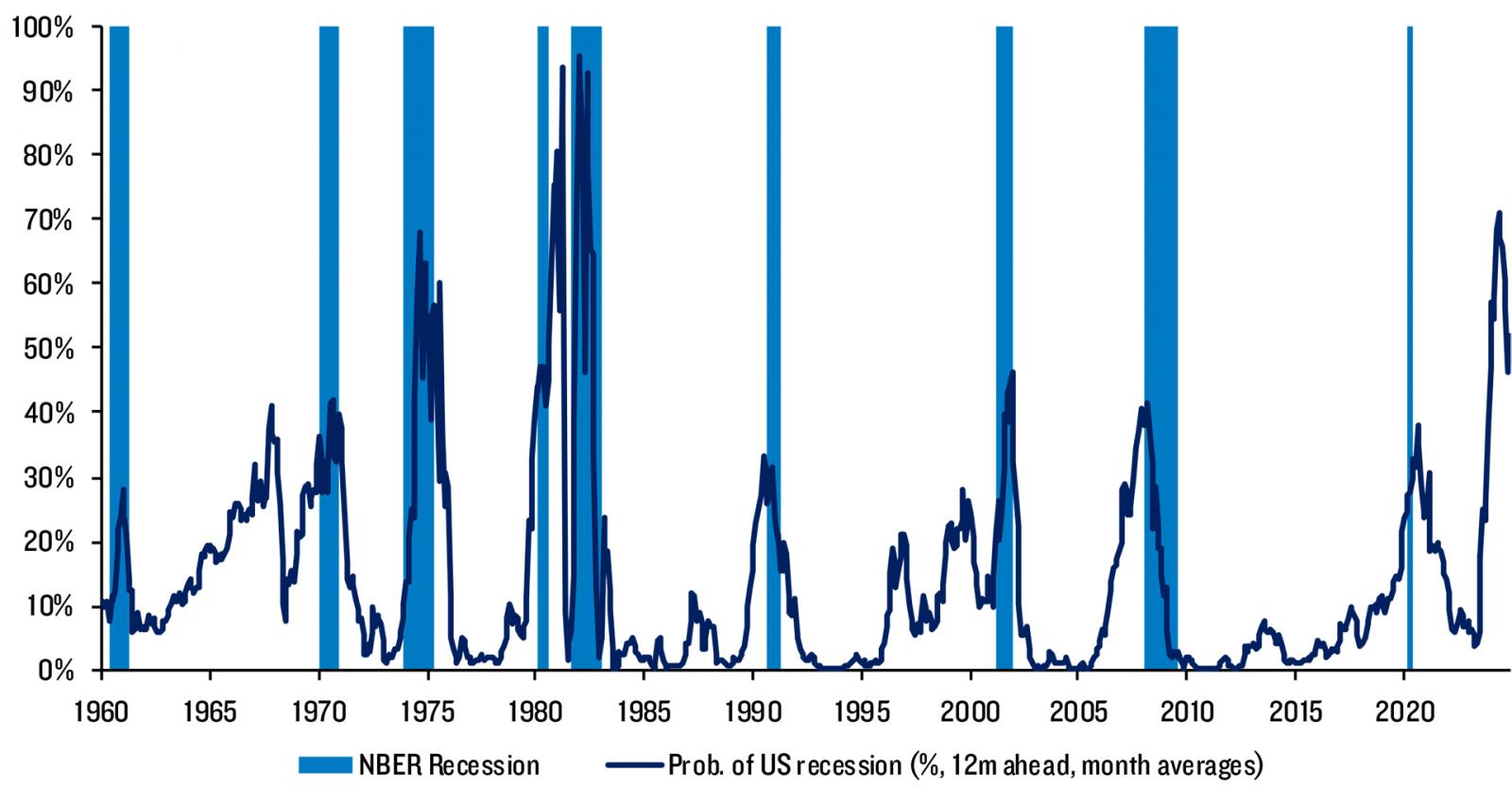

One of the most commonly used recession prediction models is based on the yield curve slope.1 Specifically, when the slope of the difference between 10-year US Treasury yields and the 3-month Treasury Bill turns negative – either with short-term interest rates high, long-term rates low, or some combination of the two – recessions tend to follow. When the model has gauged that the probability of a recession occurring over the next 12 months is above ~25%, a recession has typically followed. 2023 is the only occasion when the predicted likelihood wasn’t just close to the critical “tipping point,” but miles past it. Clearly, this model got it badly wrong.

FIGURE 2: THE PROBABILITY OF A RECESSION IN THE UNITED STATES AS PREDICTED BY THE TREASURY SPREAD*

Probability of a recession over the next 12 months

Enlarge image

Source: New York Federal Reserve, as of 30th November 2023.

* The blue bars show actual recessions, based on the NBER’s analysis. Model parameters have been estimated using data from January 1959 to December 2009 by the New York Fed’s researchers. Recession probabilities have been predicted using data through to November 2023. For more details, see https://www.newyorkfed.org/research/capital_markets/ycfaq#/

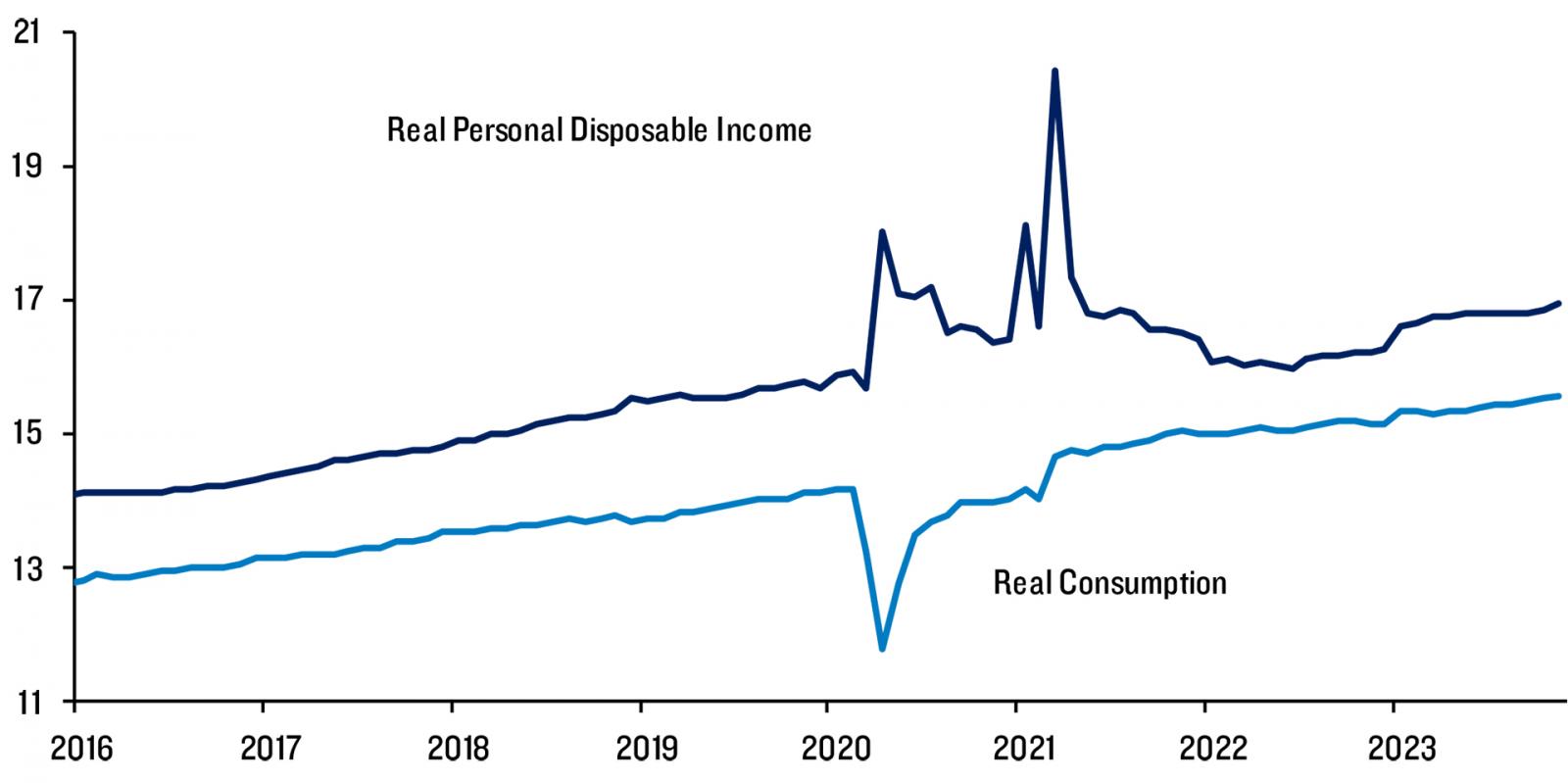

With personal consumption accounting for around two-thirds of total GDP, the consumer is key to the US economy. Generous subsidies that boosted incomes, combined with a sharp drop in consumption during pandemic-related closures, led households to build up substantial “excess savings,” which helped consumer spending to hold up more than usual in the face of declines in Real Personal Disposable Income (RPDI) – the consequence of wage increases that failed to keep up with inflation and slowing jobs growth. While 2022 saw an outright drop in the level of real after-tax income, income growth got “back in the saddle” in 2023 and started recovering – although the income level today is still shy of what one would have expected had the pre-pandemic trend persisted (Figure 3).

More surprisingly, consumption growth continued rising at its pre-pandemic trend growth rate, with the volume of consumer spending growth for 2023 now poised to register a healthy 2.2% rate, whereas last year’s predictions put it at a miserly expansion of just 0.9%.

FIGURE 3: REAL PERSONAL DISPOSABLE INCOME AND REAL PERSONAL CONSUMPTION IN THE UNITED STATES

Trillions of 2012 dollars, annualized

Enlarge image

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis. The data covers the period January 2016 to November 2023.

Why such consumer strength? Early estimates of “excess savings” turned out to be far too low: preliminary estimates of Gross Domestic Income were revised higher, and given that savings is a residual of income, so too was the savings rate.2 Easier-than-expected fiscal policy, which drove the “Disposable” bit of RPDI to do better than expected, also bolstered consumer spending. In late 2022, for example, the IMF gauged that 2023 would see the “structural” budget deficit widen by 1.3% of GDP. A year on, this estimate was revised by a full percentage point to 2.3%.3 Given the normal fiscal multipliers, this factor is likely responsible for more than half of the economists’ underestimation of 2023 GDP growth.

WHAT TO DO WHEN THE MODEL BREAKS DOWN?

When long-standing economic models break down, where can economists and asset managers turn?

Use different inputs: Implement alternate models that incorporate other definitions of yield curve slope using different maturities. For example, the Fed has used a “near-term-forward-spread” version of the yield-curve-slope model,4 rather than the more commonly used 10s-2s and 10s-3mth models.5 However, it also flipped into negative territory towards the end of 2022 and has been there ever since. So, it too has undergone what appears to be a systemic failure.

Consider non-linearities: A recession-prediction model naturally assumes that a higher expected recession probability would be bad news for equity markets. In practice, it’s important to recognize that this relationship is more complex. A recent piece by PGIM Institutional Advisory & Solutions6 showed that it’s both the predicted level and the predicted change in recession probability that matter, and the two interact to produce a much more complex relationship.

Incorporate Different Models: Consider an alternate model – such as using labor market data – to predict recession. For example, the Sahm rule7, which compares the current average unemployment rate with the lowest three-month average from the past year, rather than using the latest data in isolation. The rule shows that almost every time unemployment has risen past a certain threshold, a recession has occurred.

So, when one model breaks down, it’s critical to diversify the set of models used – whether switching to another model altogether or comparing several alongside the original.

WHAT’S ON THE HORIZON?

While the forecast for 2023 was dismal, the view going into 2024 is cautiously optimistic. The Fed’s most recent Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) took a slightly more positive view of the 2024 outlook than its previous SEP forecasts, projecting moderate economic growth rather than a recession. However, with the forecast also predicting unemployment to rise above 4% this year – the sort of increase that has historically gone hand-in-hand with recession – concerns of an economic downturn persist.

An array of models confirms this conflicting view. Yield curve slope models remain inverted. The question remains, however, whether 2023 was an anomaly and the model will get it right this time around. On the other hand, some labor market-based models, like the Sahm rule, are more optimistic, suggesting the labor market is finally in balance and thus, will protect against a recession. As investors we will watch each economic indicator with a discerning eye, but only time will tell which forecast will prevail.

While we’re still disappointed from the drawdowns in 2023, it’s worth noting that today’s economic climate – with expectations for moderate growth and further disinflation – should be a supportive one for riskier assets, despite the uneven forecasts for 2024. Liquid alternatives have, in our view, generally been a sound strategic investment in any market, and given the current conditions, we remain confident that macro strategies will resume performing as they are designed to do and will continue to offer investors a diversifying stream of significant risk-adjusted returns.

Related: 3 Timely Sources of Yield Potential to Enhance Returns