According to some business owners and Wall Street pundits, US employers can’t hire enough people because unemployment benefits are too high. We’re paying people not to work, they say.

Certainly, some people who could work are milking the system. That’s sad, but is it the only reason all those jobs are unfilled? Probably not.

Nonetheless, several governors have decided to end the federally funded enhanced benefits. Instead of the planned September expiration, they will now disappear as soon as next week in some states.

If, in fact, benefits are what’s keeping people from working, labor shortages should ease in the states that end them. I think there’s more to the story, though. This problem was already there before those extra benefits. It’s more the result of larger trends that aren’t stopping. If anything, they are getting worse.

Shrinking Pool

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce just launched a new “America Works” initiative. In their words…

The U.S. Chamber is advocating for—and rallying the business community to push for—federal and state policy changes that will help train more Americans for in-demand jobs, remove barriers to work, and double the number of visas available for legal immigrants. And the U.S. Chamber Foundation is expanding its most impactful employer-led workforce and job training programs and launching new efforts to connect employers to undiscovered talent.

All good ideas, as far as they go. But the Chamber assumes there is a large pool of unused labor, ready to fill all these job openings once some barriers fall. That’s not necessarily so.

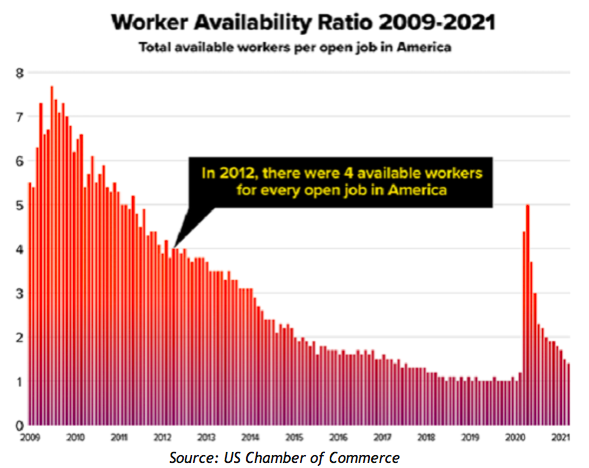

Consider this chart from the U.S. Chamber’s own report.

Comparing Labor Department data on the number of available workers with the number of job openings, there are now 1.4 available workers per job. This, according to the Chamber, is insufficient. But notice a couple of things.

First, the ratio was even lower before the pandemic—around 1.0 in 2018─2019. Worker availability is actually higher now.

Second, the ratio has been falling for years. What’s different now is it has reached a point where workers and jobs are roughly in balance. No more worker surplus means employers don’t get the luxury of picking from multiple candidates. That’s new to them and, naturally, some find it difficult.

The real problem here is we are making fewer humans.

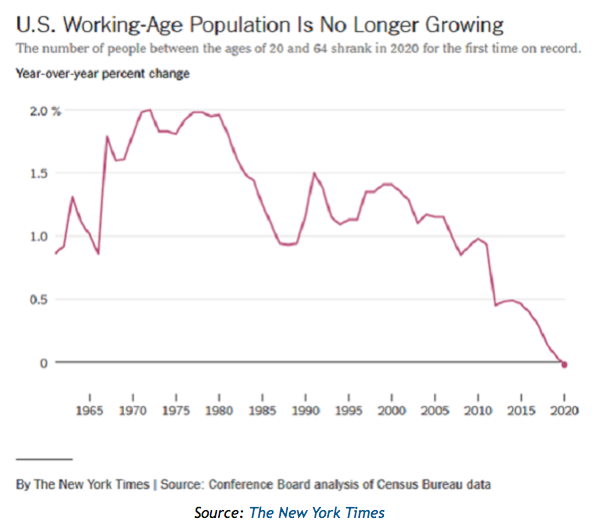

Here’s the US working age (15–64) population since 1977. It has stopped growing and is starting to shrink.

Of course people can, and increasingly do, work past traditional retirement age. Few 15-year-olds are working full-time, either. But this gives us a rough idea of how many Americans could potentially work.

Here’s another look, showing annual percentage change in the 20─64 age group.

This is a big reason employers can’t fill jobs. In many cases, the workers they want simply don’t exist.

Awkward Robots

Businesses are automating more tasks but that has limits, too. This is from a recent Wired story about a New Jersey restaurant’s experience with a robotic waiter named Peanut.

Robots also lack the kind of intelligence, manual dexterity, and people skills that any good cook, host, or server relies on to keep their diners happy. Can Peanut talk down a customer who’s irate because their eggs were fried instead of scrambled? Can it deftly plate a tuna tartare and avocado tower, and do a nice little sauce flourish around the edges? Can a robot hold back a chef who’s about to rampage because someone called their creations low-grade dog food? No way.

Even employing a simple robot like Peanut requires a sort of negotiation between machine and human coworkers. Basically: Stay in your lane, robot. “They don't come in and blend well with us,” says Julie Carpenter, a research fellow in the Ethics and Emerging Sciences Group at California Polytechnic State University. “We're negotiating how to work around them—they're not smart enough to work around us. They're not cooperative. They're not collaborative. They just follow orders.”

Because of this interpersonal awkwardness, you can make a strong case that there are some jobs that we just don't want robots to take on.

No doubt the technology will improve. That’s happening slowly, though, and businesses need help now.

Those years of worker surplus may be backfiring. Managers who could take their pick of the crop simply don’t know how to handle being on the other side. That may explain why some of the worst shortages are in industries like restaurants and construction known for uncertain pay, harsh conditions, and low job security.

Supply and Demand

This isn’t just a U.S. problem. The Chinese government, facing its own demographic decline, recently said couples could have three children instead of two. Other countries are also trying to encourage more births. None are having much success.

Falling birth rates may not be entirely voluntary. Some scientists are warning of a global decline in sperm counts due to chemicals in the environment. Others dispute that idea. But whatever the reason, we’ve stopped making as many workers as the economy needs.

The law of supply and demand says this scarcity makes existing workers more valuable, letting them insist on higher pay and better conditions.

In other words, the long-term outlook may point to an economy composed of better-paid workers, with the higher wages possibly coming from lower business profit margins.

What would that economy look like? A lot different than the one we have now.

The Great Reset: The Collapse of the Biggest Bubble in History

New York Times best seller and renowned financial expert John Mauldin predicts an unprecedented financial crisis that could be triggered in the next five years. Most investors seem completely unaware of the relentless pressure that’s building right now. Learn more here.

Related: Vaccines and Inflation Risk