A headline jumped out at me the other day:

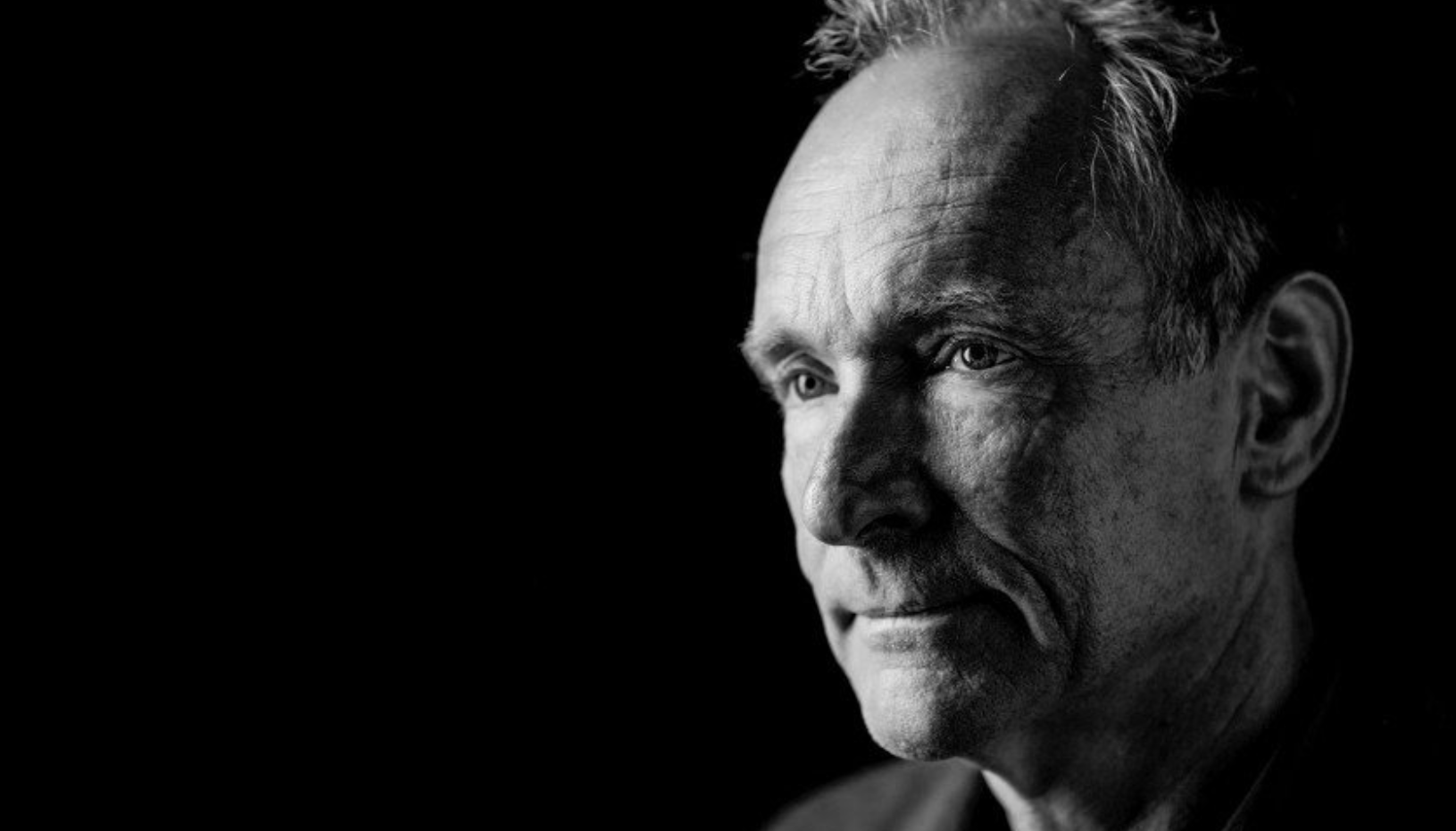

World Wide Web inventor Tim Berners-Lee calls crypto ‘dangerous’ and likens it to gambling

The key points he made in an interview with CNBC are:

- Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web, called cryptocurrency “dangerous” and likened it to gambling.

- Discussing the future of the web, Berners-Lee said digital currencies are “only speculative” and compared it to the dot-com bubble.

- Berners-Lee said, however, that digital currencies could be useful for remittances if they’re immediately converted back into fiat currency when they’re received.

I’ve heard so many in banking say that crypto is bad, blockchain is good, but I was surprised to hear Tim Berners-Lee saying it. So I delved deeper and listened to his interview with CNBC on their regular podcast Beyond the Valley.

The discussion takes place between CNBC’s Arjun Kharpal and John Bruce, the CEO of Inrupt, and Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the co-founder of Inrupt. Inrupt claims to be: “a worldwide movement of inventors, investors, technologists, business leaders and governments who are committed to a web that works for everyone”.

Here are a few hand-picked quotes and a slightly edited transcript of the whole discussion.

“We see entities that sit astride silos of data or consolidation of data in a way that’s not practical. We don’t get the value out of the web that we could. Data is used for the benefit of others, not the citizen or the consumer ... should users have control of their data or not? Well, in our world you should.” John Bruce, co-founder, Inrupt

“Give everybody a little bit of cloud storage, their own personal cloud storage, call it a Solid pod, they have complete control over that … Web 3.0 is different. The third layer of the web is these protocols we built on top of it. It’s not blockchain … blockchain is public, expensive and slow. We have to be the reverse. We have to be private, faster and cheap … for something like digital identity, the blockchain’s okay. But just storing data, personal data? Doesn’t apply. Doesn’t work.” Tim Berners-Lee, co-founder, Inrupt

“Cryptocurrencies are all Ponzi schemes”, John Bruce, co-founder, Inrupt

“A digital currency not linked to anything and only speculative, obviously that’s really dangerous. Cryptocurrency can be 100% speculative. Investing in things which are purely speculative isn’t the way I want to spend my time. But using it for remittances, that seems to me to be the most useful thing.” Tim Berners-Lee, co-founder, Inrupt

“Alexa, who do you work for?” “Actually, I work for Jeff Bezos. I work for Amazon. I don’t work for you.” Tim Berners-Lee, co-founder, Inrupt

Beyond the Valley (script edited to flow on the blog)

Arjun Kharpal:

Hello, and welcome to another episode of CNBC’s Beyond the Valley. I’m Arjun Kharpal here in London. And I’m not going to give you a big long intro here, I want to get right into our conversation, because it’s a fascinating one on the future of the web, on data, and where we all go from here. And I want introduce to my two wonderful guests today. John Bruce, the CEO of Inrupt, and Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the co-founder of Inrupt and, of course, the inventor of the World Wide Web, just a small mention there. I just want to kick off the conversation on a broader theme with you two here. There’s been a lot of discussion about the state of the web as it stands, what the current internet landscape is like. What are the current problems with the web as you see it right now? John, I’ll come to you first. As you see it? And what are some of the steps that in your view need to be taken to fix it?

John Bruce:

Well, I can talk about the experiences I’m facing as I go around and about the world talking to corporations and governments about the challenges they’re experiencing. And the common denominators are, we’ve got to a place where, and we see this on a macro basis on the web, but on a more particular basis, we see entities that sit astride silos of data or consolidation of data in a way that’s not practical. And the consequence of which is that citizens and consumers, you and I, Tim and everybody else around here, we don’t get the value out of the web that we could.

Our data is held in places that are not accessible to us and the utility of it is lost. I mean, the data is used for the benefit of others, not the citizen or the consumer. And inversely, corporations and governments are challenged by the consequences of assembling all these pots of data about individuals, but not combining them in a way that provides utility for them as entities that want to provision the service of the product. Or inversely the citizen, the consumer who wants to enjoy a relationship with all these entities that’s productive, that gets utility out of their data.

So, what fascinates me most about the opportunity to do our bit to change that, is that it’s available to us. All the data exists, it’s just a recomposition of it, making it available in a form that isn’t available today for the benefit of everybody. I mean, it’s a truly consequential change we can make.

Organizations, individuals and the people who glue it together, the developers, can all operate in a way which is way more efficient than the way we have today. And, Tim and I enjoy the opportunity to make a significant difference here. So, that’s why Inrupt.

Arjun:

And you spoke a little bit about the amount of data, and hinting towards, I guess, what we see now is a landscape in the internet where there are large players, large players of this world. You look at the Googles and Amazons and Facebooks of this world, which of course, collect large amounts of data for their products on users. Tim, this question to you. I mean, what are the challenges then as it stands with the internet landscape as it is given, the dominance of a lot of these large players and the data they’re collecting? What are you concerned about at the moment?

Sir Tim Berners-Lee:

So, I suppose one way to think about this is to go back to the web of years ago. And back then if you were sufficiently switched on and geeky, you could get yourself a computer and you could put a web server on it. You could plug it into the internet and you’d have a website. So anybody could have a website. Not everybody had the internet back then, but the spirit of the web was incredibly empowering to individuals, because you could put your website up. CNBC or the Financial Times could put a website up and you could all link to each other. And the blogger’s sphere in a way was this tremendous feeling of individual personal sovereignty. My website is right out there. I’ve got my domain name and now I have power, the same power as all these big companies.

What’s gone wrong with that picture? Well, everybody’s on Facebook. So now they don’t have the website. They all use Mark Zuckerberg’s website. And on there a few things they’re on. Partly it’s innovation when people have their own websites and they wrote their own code and tweaked their own websites, it was crazy, all kinds of things. And then people tried to MySpace where you could have quite varying spaces. But then, what happens on Facebook, when people look you up on Facebook, you don’t control what they see. You don’t control anything. Mark Zuckerberg’s algorithms control what news gets fed to them, as they’re looking at your stuff and so on. And so, that’s very disempowering.

It’s very useful to Facebook. They have a lot of data about people. That data they use for targeting them with advertisements and particular political advertisements, other famous celebrities views. But, what we’ve lost is the ability for individuals to have power. So, stepping back, can you imagine? So if Web 2.0 is this rather dysfunctional one, where you have these huge silos, where we have just Facebook where everything happens inside Facebook and Google and LinkedIn, but you can’t actually share your link. You can’t share your Facebook photos with your LinkedIn groups, because these groups aren’t accessible subjects on the web. They don’t have URLs. A LinkedIn group is only a thing within LinkedIn. The Facebook group is only a thing within Facebook. So, when people think about it, they realize: “Yeah. That’s a pain. I would prefer a world in which I could just share across the platform.”

So the third version of this, if you like Web 3.0, we just have small protocols. We’ve still have HTML, we still have HTTP. We have the IDF data format. Basically, we add a single sign-on across the web called Solid. You don’t have to choose whether to log in with Facebook or log in with Google. Log in with Solid and it works everywhere.

And, in a way, that’s obviously useful. Obviously, we ought to have that. And so, just giving the universal sign-on is one thing. And then, when you give everybody a little bit of cloud storage, their own personal cloud storage, call it a Solid pod, they have complete control over that. It’s a bit like a Dropbox account, it’s a bit like a box, it’s bit like a G drive it away. But it runs a Solid protocol.

And the neat thing about the Solid protocol, the release of Solid ... The massive innovation here is that if you have your Solid pod which runs this project, runs the Solid protocol, then any app can run data right into it. So at the moment, if I run a writing app, it would be a total pain for me to write the code to store stuff on a G drive this way. So, what we’re doing is, we’re saying there’s a new world in which, when you run an app, it asks you where you want to store your data, and you say which pod you want to put in. And then all the data in your life goes into that pod. And that is really enabling.

John:

And there’s the yin and the yang of Inrupt, actually, which is the personal empowerment and the opportunity for individuals to take more command over their role on the web, and the utility for enterprises and governments, organisations to service the users in a much more productive way for everybody. Right? So, it’s a fascinating blend, actually. Really potent blend of two hugely, I think, potent opportunities to make a significant difference on the web, coming together for the benefit of everybody.

Tim:

Solid is a protocol, it’s open protocol. Solid is the platform, the open platform. Inrupt is the company.

John:

Tim created it at MIT and a bit of background. Tim and I met around six years ago, when he was a professor at MIT. He had been working for some years on this project called Solid, and Solid was a way of taking the constructs of the web and, by reorienting them, getting us to a way better place. I was at IBM. When Tim and I met, the notion was we could move the central gravity of Solid out of MIT, and continue to invest in the open source efforts but, at the self-same time, we could then put a resource set together which we called Inrupt.

Inrupt is a company with capital and people and a roadmap and so on, to galvanize the efforts to take it from an open source protocol to a new way that the web could work. Then, by building an enterprise grade version of it all, we could make it safely and scaleably available to governments and organisations who wanted to get utility out of the web, and out of the data available on the web, in a way that was much more productive for everybody. So we came together to do that.

Arjun:

And how do you get buy-in then? I understand from a government perspective, but as a private company who thrive on data collection in order to improve their products, and they thrive and really want to own that data, how do you then get buy-in from companies like that, when that has been their business model?

John:

Therein lies the rub. Right? Thrive is an interesting word. The corporations we find ourselves talking to realize that the road they’re on, with this endless trudge to get more data, is a sliding scale of return on investment. Right? We’re in the margins of the margins when it comes to return on that kind of investment. But everybody, so myopically looking at this whole trudge we’re on that when you say, “Can we just ... “ Sorry, Americanism. “Can we just take a breather? Because there’s another way of doing this stuff, if we’re prepared to engage the process to get there.”

And the other way of doing it is instead of figuring out blindly, are you a likely candidate for my product or service? How about I just ask you, in a legitimate way, and you tell me? I’m oversimplifying it somewhat, but not greatly, actually. So, this notion of engaging your potential consumers in a collaborative way to determine what they want to buy and when they want to buy it and how much they want to pay for it and so on, is way better than trying to speculatively determine, based on your height where you live, what your car is, whether or not you’re going to buy my bike. [inaudible 00:11:25] Somewhat so.

Tim:

For example, suppose you’re a travel agent, and you’re on the web and you’re trying to sell vacations, holidays to people. And, at the moment what you do is you put ads and you’ve got this great holiday which you think will apply to a particular demographic. So, you go to Facebook and you get these ads which are amazingly targeted, just the sort of people you ask. And so, they see the ads. This is now flipped around. This is the intention economy, not the attention economy. This is somebody who goes to the travel agent and said, “All right. We had a pretty good vacation last time. And we’ve had three vacations, but actually we want something special and really, really different.

“And, by the way, we can open up the Solid pod with all of the pictures we’ve taken at all of our holidays. We’ve got all of the flights that we took. We’ve got all of the reviews we left on all the restaurants. We’ve got all the menus that we took in data in our pod. And, suppose for 24 hours you get access to all that. You run your AI on our data. You find us a brilliant holiday and then you forget it.” So, you’re empowering. When the individual’s got all this stuff about their lives, they’re very, very empowered by it. And if you’re a travel agent or whatever you are, then you do well to actually flip over to this. Enjoy the world where the user’s offering so much more data than you ever get from Facebook.

Arjun:

Tim, in your view, how much of the success of this really taking off is predicated on the change in user behavior, and how much do users really want to take responsibility for their data? Right now we go through this process. We go to a website, we accept or reject cookies or we can tinker with some privacy settings on whatever app we’re using to say, “don’t collect this data,” or, “don’t”, and there are options there. It takes a lot of effort. I’m sure most people don’t do it, even though the options are there. So how much is it about changing consumer behavior? And how much are you seeing that behavior and that willingness to change?

Tim:

There will be a huge change of behavior, but it won’t happen from us standing here and all saying, “Hey! June the first everybody. Drop Facebook, drop Instagram, drop Google. Okay?” It’s bit by bit things change.

We never actually did any for marketing but, as we started the company, people realized what we were doing. We got incoming interest. We got incoming interest from the NHS in Manchester. We got incoming interest from the Flanders government. And the Flanders government said, “You know what?” The head, their minister, president, had said to a camera, “Everybody in Flanders should have control of their own data. Because of GDPR and because of a more efficient economy and, post-COVID, this country, this region’s got to pick up fast. And it’s got to be very efficient, so we want to have all of the data, personal data to be very interoperable across the government and across companies.”

So, he had that vision. It was important for his citizens. What’s happening now is that they’re rolling it out, bit by bit. Different government services will actually use the pod. And people will login with a government ID, a Solid ID, and it’ll work in other things. In fact, they’ll find the pod is actually pretty useful for doing other things. But it doesn’t matter. It’ll be bit by bit.

And so, the web originally spread but it didn’t spread suddenly, with everybody switching to it. It spread among physicists, because those are the people who paid our salaries. So, it started off at universities. Then it moved across to the States. And nobody else knew about it. Then it moved to the local library there and they moved into the libraries. And, in fact, every time the web spread by another factor of 10, it’s spread for a different reason. Now the same thing is with Solid, except that, with the web, if you get something grows by a factor of 10 every year, then in ten years you’ve got 10 to the 10, you’ve got the planet, more or less. And we’ve done that. Been there, done that, got the T-shirt.

But what’s happening, we can’t afford to wait ten years for Solid, so the Flanders government comes to us and says, “Can we give everybody a Solid pod?” We go, “Yep, that works.” So, we’ve got this incoming stream of governments and other guys.

John:

Corporations are the same, as well. But the principle of your question is binary: should users have control of their data or not? Well, in our world you should. You should have control of your data. I mean, it’s your data. So having said the principle is absolutely a sound one, users should be in control of their data, now the question is how do we get you there? How do we get you there in a way where it’s not a step function in your behavior. And that takes steps. So, the corporations we’re working with appreciate this, and governments do.

But the corporations appreciate that we can’t change everything overnight. Your user buying behavior, user interaction with organizations has to evolve. So, what motivates them to behave in a particular way? Incentives. And I don’t mean that we have to pay you to do it, but rather show you some experience of a new way that you, as an individual, could enjoy a relationship with a provider that’s better than the one you’ve got today and you’re going to adopt it. And having adopted it, it moves on again, you’ll continue to adopt it.

So, that progression from where we are to where we’re going to, that’s what we’re working on with corporations. It’s not an overnight change. It’s moving towards an end state.

Arjun:

And along this journey, how much of a challenge, John, is it when we are getting into a world of increasing tensions geopolitically? And where blocks and governments around the world are becoming, to some extent, technologically more siloed. Particularly with data. What challenges does that pose to this kind of arena, where you want users to be in more control of their data, but you also want it to be somewhere that they are able to share data willingly and across the world, and for any product and for any service?

John:

Well I think there are more likely landing zones for change than others. I don’t mean to imply any disrespect, as we could name names together where it’s less likely to be adopted than other territories, but the ones we’re engaged in today are classic democracies who see the merit and the virtue in giving their citizens control over the web. They want to make that available to them. Similarly corporations with a brand, where part of their brand is trust and, if you’re a CEO of a corporation, you can make a hard determination between the increase in trust perception of your consumers and the return on your investment. There’s a science to all this stuff. So, by virtue of deploying a technology, as companies are now beginning to, where you’re demonstrating to your consumers that you appreciate their trust and you don’t just say it, you walk the talk, you get a profound shift in the relationship. It becomes one where consumers see your brand, which is already hopefully somewhat measurably trusted, and it becomes increasingly trusted.

Arjun:

Tim, you mentioned Web 3 and Web 3.0 earlier. When people are discussing what the future of the web looks like, they often use these terms interchangeably, and they’re quite ill-defined. So, Web 3.0, what does that mean to you? What does it look like?

Tim:

Web 3.0 is the third layer of the web as we call it. There are protocol layers, if you like. Solid protocol is the seventh layer of the web. The geeks will be talking about the layers of the protocol stack and certainly the transport layer and the network layer and so on. And those are deep in the network, but layer seven is the application layer, where we actually provide functionality by getting people to be able to use the same data on different apps. That’s where Solid is. It’s much the standard. It’s nothing to do with blockchain.

Vitalik Buterin was here. Right? He wrote in a blog. He said, “What we’re doing with Ethereum, that’s what we call Web 3.” Well, he calls Web 3, is what the project they were doing with Ethereum.

It’s unfortunate, because we have spent so much time since then saying, “Actually, the Web 3.0 is different.” The third layer of the web is these protocols we built on top of it. It’s not blockchain. You could look at trying to use blockchain for a Solid pod. Suppose you want store medical data, you could put it on a Solid pod. It goes over the internet, gets stored basically into a database into a file. File systems out there in your pod. And suppose you take that medical data and you store it on blockchain.

First of all, the way the blockchain works is, the moment you put it on the blockchain, the same data has to be put on every single node on the blockchain. So, your medical data has now been put on every node and it’s completely public. So, everything that’s on the blockchain is public.

It’s also expensive, because there are gas fees. Basically, the way blockchain is made, and it works in different ways on different blockchains, but basically the way it works is you have to pay fees to get something. So do you want to have to pay fees? And also it’s slow, the whole blockchain process. There are lots of blogs written by developers who tried to make web apps that just do stuff on there.

So, blockchain is public, which is not what you want for your medical data, it’s expensive and it’s slow, and we have to be the reverse. We have to be private, faster and cheap.

There are things you can use blockchain. If you want to say, “This is me. Everybody, this is my key, my public key. And this is my face and this is my identity.” So, that’s reasonable, because it doesn’t mind being slow. You want it to be public and seen by everybody. So, for something like digital identity, the blockchain’s okay. But just storing data, personal data? Doesn’t apply. Doesn’t work.

Arjun:

So, in that case, where do digital currencies stand? Because, again, there is a chorus of people who say, well cryptocurrencies, digital currencies, tokens of some form are going to be key to what the future of the web looks like. You’ve got companies that are offering blockchain based cloud data services and you’ve got to use a token to use them. What happens in your world?

John:

I don’t care what they say. I don’t know that cryptocurrencies are all Ponzi schemes. I mean, I think that there’s a relevance in that. I think it’s massively overstated though, in terms of a new way for sovereign control over currencies that doesn’t require regulations. I mean, we’re all reading the press. You see the implications of technocrats who try and sit astride huge currency exchanges and so on. One of our number, I may have mentioned to him to you earlier, Bruce Schneier. He’s our chief of security. And Bruce has been very forthright actually in his opinion of cryptocurrencies. And if ever there’s a guy who knows about crypto, it’s a guy who wrote the book on crypto.

Applied Cryptography was the defining moment in crypto, I think, over the last couple of decades. So, Bruce’s opinion and well publicized is I think, consistent with the one I am, and I suspect Tim’s too, which is, we’ve just got to be really, really, really careful we don’t overreach with all this stuff. And the folks who are heavily invested in it, either from a commercial perspective, investors or from an ego perspective, because it’s their baby, they designed it, will make massive representations in a way that’s I think totally inappropriate for cryptocurrencies and the like.

Arjun:

Tim, I’d love your take on that as well. I mean, with cryptocurrencies in particular, there’s many as I mentioned who say, well this is very much part of the future of the internet of the web. And it’s key if we want to achieve any kind of decentralization on the web. A bitcoin global currency, some say. So, what’s your view?

Tim:

So I remember the dotcom bust, boom and bust. I remember sitting there talking to people and people were saying: Why invest in this stock? This is a company that just opened a website for selling cattle in Texas. But the market cap of the website is greater than the value of all of the cattle in the whole world. People will say, “Why’s that?” And the answer? Why was that the thing? Why was it valued at that? Because people were just valuing it, because of what they imagined other people would value it in the future. So, in other words, it wasn’t based on revenue or in reality.

Then the bubble came, because what you were prepared to pay for is what you think other people will be prepared to pay for it in the future. And so, something like a digital currency, where that’s what happens, where it’s not linked to anything and only speculative, obviously that’s really dangerous. If you want to have a kick out of gambling, basically, it is just speculative. Cryptocurrency can be 100% speculative, not linked to anything at all. Whereas, at least that poor website for selling cows was, it did have a revenue even though it was flawed. So, basically, investing in things which are purely speculative isn’t the way I want to spend my time. But using it for remittances, that seems to me to be the most useful thing. If you transfer stuff into blockchain because you can get that immediately to your family.

John:

There’s utility there.

Tim:

There’s utility in that. Just don’t keep the currency. Get rid of it, put it back into USD or something.

Arjun:

Let’s talk about some new technology as well then, on top of what you’re up to. The development of artificial intelligence is one that’s been poured over for many, many years and we’re starting to see some breakthroughs that are getting through to the mainstream. One of the more recent ones is ChatGPT from OpenAI. It’s caused a lot of stir in the corporate world. And also it’s just really hit the mainstream. How important a breakthrough is this in terms of AI?

John:

Is it a breakthrough or is it evolution? In the sense of it’s fun to go in there and play around with it and so on, but I dare say it was fun in the 1960s when MIT first did their version of it. It’s an evolutionary path we’re on. I think there’s a cautionary note or two in there about the way it can be weaponized. But, great utility for rudimentary customer support, customer service and so on. I mean, if we’re talking about the ChatGPT-type constructs.

AI generally, though, has got immense utility. But it’s software, it’s algorithms, it’s coded written to order. We’ve got to be careful we don’t assume that what we’re getting here is real intelligence. We’re getting just a proxy for a load of consequences of algorithms that run and give you a result.

Tim:

ChatGPT has been around for a while. It’s not a revolution in the power of AI. It’s just a revolution of making it really easy for anybody, anyway, to use. And there are concerns. I know the folks at Google point out that they’ve actually had that sort of power for a while, but they haven’t released it because they are worried about it being used for ill. The ability to deep fake and stuff is serious. And how do you build a system which can do people’s homework badly, but can’t be used for deep fakes in spamming or phishing attacks? There are a lot of issues around there but, in general, we’ve all been trained to ask AIs for ndigital assistance for things.

When you talk to an AI’s worth, ask it who it works for? “So Siri, who do you work for?” “I work for Apple. I don’t work for you.” And so, “Alexa, who do you work for?” “Actually, I work for Jeff Bezos. I work for Amazon. I don’t work for you.” So, one of the things we’ve been thinking about, to flip that around is that, when you have a Solid pod and you can run an AI on your pod then that AI will see that, in your pod, you’ll have the stuff that you’ve bought from Amazon, but also all of your nutrition data or everything you’ve eaten. It will also have all your fitness data on your health. So in a way, when you run an AI on your pod, it’s actually going to have access to much more really, really cool stuff than any of the things like Siri and Alexa that operate over these silos because they are silos and they’re limited.

Your pod integrates everything. It’s personal data integration, if you like. Like enterprise integration, if you remember that being your thing? It still is. Integration of all the data within your life and then run AI over that and that is sweet. We call it Charlie.

Arjun:

Charlie?

Tim:

Charlie is an AI that works for you. So, “Who do you work for, Charlie?” “Well, I work for you.” “What do you mean?” “I mean, I am legally your agent, just like your lawyer.” “Oh, okay. So in that case, Charlie, I will trust you with all my data. And so, I will expect you to be able to be much more insightful.”

And so, the power of AI is that it all depends on the data. You’ve been able to run AI on public data, and people will be able to run AI on clinical data, just the clinical data. But Solid pod, you have the whole data spectrum. All of the data to do with your collaborations and your coffees and your projects and your dreams and the books you’re reading and stuff. And all of your life then is in your pod. You run AI on that? That could be sweet.

Arjun:

We’re going to bring this conversation to a close. It’s been absolutely fascinating and I want to think a little bit about what the future looks like for you both. As you’ve spoken to all these different changes to the web, internet model, to protocols and how we may have more control over our data in the future, if these things come to pass.

John, I’ll start with you. If these things come to pass, what does that mean then for the way that the internet is distributed right now? We started off this conversation by talking about companies like Google and Facebook and others, who have large amounts of data, who have very strong positions in the verticals they play in, and across different areas. What does this mean for them? Do you see a world where they are out of business? Is that too far?

John:

They’re really smart people. Right? I mean, they’re well resourced. They’re brilliant people. We know a bunch of them. As I said, when I first met Tim I was at IBM, a company I’m quite fond of in various ways. And that’s been a high technology business for over one hundred years. Just think about that. A high tech leader for more than hundred years.

Think about all the changes we have in the last twenty years, let alone one hundred years, and how do they prevail? Because they’re smart, well resourced, they change, they adapt, and they realise the consequences around them and they adapt to suit. Otherwise, they go bust. So that notion of evolution, applies to Google and Facebook. The folks who we believe are big incumbents setting astride data models, business models that aren’t changing will die as I think they’re very changeable.

I mean, we’ve mentioned Facebook a bunch of times and my wife, I’ll tell you this as an aside. My wife runs a fabulous photography business and she lives in mortal fear of what Facebook might do to her, because they could kick her off. And then her business model changes quite fast, because that’s how she gets a lot of our custom. And the group she’s in similarly. But she would pay Facebook for the relationship that they could provide her, as long as they weren’t taking her data and using it in untoward ways. I’m not a Facebook user but, if I were, I’d pay nine bucks a month, but please don’t take all my data and abuse it. Give me the platform to operate on and I’ll give you fair compensation for it. And that notion of service delivery for fair compensation, that’s a nice balanced, benevolent relationship between a consumer and a service provider.

I think that we’ll see them adapting, but we’ll see other entities emerge, just as we did when the web first evolved. Right?

We saw massive shifts. Businesses that evolved in a substantial way. Not the pets.com, but I mean substantial businesses that evolved over time using the web in the right way. And I think we’re about to experience that again. I hope that, and I would expect actually some of the corporations we’re working with will be, because they’re smart enough to see what the opportunity represents and are beginning to mobilise, to take advantage of it. They’re not stuck in the rut that we talked about earlier.

Arjun:

And Tim, your view on that, the big players? I mean, does the nature of their power change in a world where Solid pod is the gold standard?

Tim:

Well, of course, and it’s not just the technology. It’s the technology and the policy. There’s the GDPR people. One of them came to MIT, an Italian professor. So we’ll talk about Solid and say, “Well, if the people who are writing the GDPR policy want the power that people will get through Solid, everyone will.”

So sometimes you get Solid.

There’s this huge backlash in a lot of MEPs and people in the policy space that have been thinking about how, if necessary, there will be policy and necessary legals to back this up but, once people see the possibility of putting together the technology with the policy, then it will become something else. People will get just addicted to it. You’ll get addicted.

You’ll start off maybe using something which is Solid-based. And it’ll work a bit like the web. You start off using it just for some game or you start doing some Wordle on it or something, or you start doing some doodle-like thing about when you can plan a meeting. But then you’ll realize that the Solid-based meeting, there’s the things which like Zoom, when you’re with your friends when you’re going to meet. Then suddenly, when you’re going to meet, it’s giving you meeting tools, it’s giving you video conferences, it’s giving you things to help you write, to track the agenda and the program and the minutes. And then it’s helping you create a meeting series and you’re creating a club around that. And it’s helping you then inform them.

So you have lots and lots and lots of collaborative tools which people are building out there, and the Solid world will become more powerful. People will realise that anything which works and doesn’t give them data in their pod is robbing them of the power.

Bit by bit things change. It won’t be sudden. There won’t be suddenly a day when everything switches across. But just incrementally and inexorably, everything will be moving into this new much more powerful world.

Arjun:

That was such a wide-ranging, fascinating, and in-depth conversation. Tim, John, thank you so much for your time.

Related: Will Silicon Valley Bank Kill the Fintech Industry?