“When you’re not working, what do you do to de-stress?” was the last question Greg Becker, CEO of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB)*, took at an investor conference on Tuesday last week. “Cycling is my advice,” he replied. Three days later he was on his bike as his bank went into receivership.

You've probably seen a lot about Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and it's demise by now - the collapse of the bank pretty much dominated my social media feeds throughout the past few days - but I spent a lot of the weekend trying to do some forensic analysis of what happened to them. Net:net is that the problem SVB encountered is the pandemic flee to savings, deposits, digital and tech investing and then the post-pandemic reversal, combined with a completely flawed strategy of investing in illiquid assets and securities. As TechCrunch puts it, the bank shot itself in the foot.

Well, it is a spectacular failure of management of the bank. As Mayra Rodriguez Valladares points out in her column on Forbes, it is actually SVB’s CEO Greg Becker, his team, and the bank’s Board of Directors who are responsible for this colossal failure. Yep, Greg Becker, the guy who sold his shares just before the bank collapsed* but, more importantly, the flames of its flaws were fanned by social media.

When Peter Thiel's Founders Fund said that investors should pull out of SVB, it went viral and led to a mass meltdown. That seems strange for a bank that was the sixteenth largest bank in America and voted one of the best. Even a few days ago Jim Cramer, CNBC's leading stock picker, was calling them a buy.

Just last week the bank was voted one of America's Best Banks for the fifth year on the Forbes Financial All Stars List. There was a tweet celebrating this on March 6 ... but it's now been deleted as, within just a few hours, the bank went from hero to zero, and was shut down by the regulators on March 10. What happened?

They, for some stupid reason, decided to take a mass influx in deposits and invest them in long-term securities, thinking there would not be a deposit reversal. Duh? Basic bank policies says you need to keep some liquidity. To put this in perspective SVB saw a massive rise in deposits in 2021, from $61.76 billion at the end of 2019 to $189.20 billion at the end of 2021. Then they saw a reversal when deposits fell from $198 billion at the end of March 2022 to $165 billion by the end of February 2023, which left them with a gaping hole.

The problem with deposits is that you don’t want them en masse for a long time. You want to use deposits for a short time in order to lend long-term, as that’s what makes the money. But you need to keep a good chunk of deposits in the back pocket, in case customers ask for their money back. In other words, banks make profits by taking money in as deposits, and then leveraging that asset by lending at higher interest than the amount it costs to store those deposits. It’s very basic.

So, in the case of SVB, they saw this massive increase in deposits but could not explode their loan book to match it. As a result, they took out a whole load of less liquid assets in the form of mortgage-backed securities. But then they've used this strategy for a long time. Back in 2001, it was clear that the bank's strategy was to borrow short (take deposits) and loan long ...

Mortgage Backed Securities (MBS) are investment products matched to the buoyancy of the housing market which, if you haven’t noticed, has been pretty poor in most economies this year. SVB, as deposits grew, purchased $80 billion in mortgage-backed securities , and that money was tied up in what is called hold-to-maturity. In other words, you keep them for a long time. 97% of these MBS securities were for a ten year or more duration.

And there’s the rub. A massive increase in deposits leading to a massive investment in long term borrowing securities, and then the government makes a move. The Federal Reserve raised interest rates in 2022 and continued to do so through 2023, which caused the value of SVB’s MBS to fall through the floor combined with a run on the bank where investors asked for their money back. It was a lose-lose. This issue was pointed out by Dan McCrum, he of Wirecard fame at The Financial Times, alongside his colleagues Tabby Kinder, Antoine Gara and Joshua Franklin in late February:

SVB’s market capitalisation has fallen from a peak of more than $44bn less than two years ago to $17bn today (February 22, 2023). But some analysts, shareholders and short sellers point to another problem of its making: a move to put $91bn of its assets into a poorly performing bond portfolio that has since amassed an unrealised $15bn loss.

Similarly some were questioning their investment position even earlier.

So far, so difficult but, to add fuel to the fire, SVB announced on Wednesday that they had sold $21 billion of their securities at a $1.8 billion loss, and were raising another $2.25 billion in equity and debt. This came as a surprise to investors, who were under the impression that SVB had enough liquidity to avoid a fire sale of their securities portfolio and started pulling their money out. The issue is when people take their deposits out, do you have enough money (liquidity) available to pay them? And that’s what happened with SVB last week and the answer was no. A bit like Northern Rock in 2008 (Ed: remember them?), if all the customers want to take their money out at the same time, then the bank collapses.

Then, as The Times noted, shares in SVB fell 60% last Thursday and were down more than 40% in pre-market trading on Friday and by Friday evening, the bank was shut down by the regulators. Investors had withdrawn $42 billion of assets in just a few hours, a fifth of its assets, and the bank was collapsing.

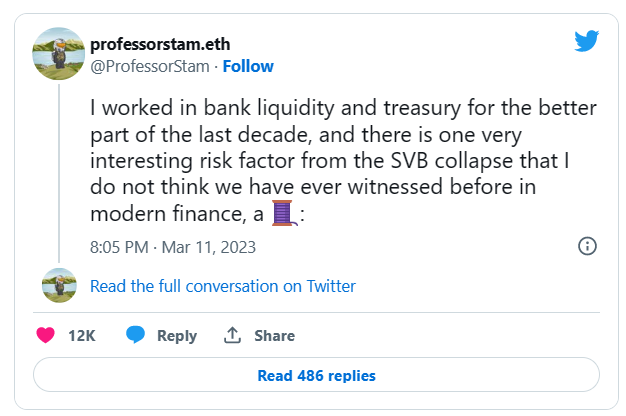

The main reason for the shares plummeting was that investors were worried whether the capital raise they called for would be enough to stem a decline in deposits. SVB faced a bank run because their main supporters, such as Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund and other prominent venture capitalists, had advised portfolio businesses to withdraw their money. That advice was then amplified by social media so that everyone did a real-time run on the bank. It's not like Northern Rock, where customers had to stand outside branches; it's basically a radical withdrawal of support by investors in real-time on the network. So much for Silicon Valley.

Then you have specific issues, such as SVB is the bank for many start-ups in FinTech and technology in general and now these firms will be wondering what to do next. Thanks to the FDIC and bank license guarantees, startups and investors with SVB can expect to get $250k (£85k in the UK) back, but that process will take a while to be sorted out and, if you had more than this deposited with the bank … well, tough. For those who didn't withdraw funds last week, or who didn't have money sitting in several accounts, the next few weeks could be very hairy.

Will startups be able to make payroll? What alternative financing is available to them? How can VCs step in to help? Are any VCs in trouble? What happens if SVB gets bought?

For tech startups, which for decades have relied heavily on the bank based in Santa Clara, Calif., it has set off a crisis that could lead to mass layoffs, or hundreds of startups collapsing, according to industry insiders.

In particular, for British tech firms, there is a huge fear that they could go under. As The Times reports:

“Rippling has historically relied on Silicon Valley Bank for payments rails for our payroll and other products. We discovered this weekend that SVB had unexpected solvency challenges. Just now, we learned that the FDIC had stepped in and effectively shut down SVB. Pay runs in flight for today out of SVB have not been paid.” Parker Conrad, CEO, Rippling who depend on SVB for payments

This is seriously worrying.

In fact, it even got centre stage on Laura Kunssberg's Sunday morning BBC show as she asked Jeremy Hunt, the UK Chancellor, what was going on:

Kuenssberg: It all feels like it could be pretty terminal for UK tech. The Prime Minister is going big guns about creating a great place for innovation, but this Monday at least 200 firms employing thousands of people will find they can't pay their staff or their suppliers, because the bank they had an account with has gone bust. Investors estimate that thirty to forty per cent of UK start-ups could be affected. I know the Bank of England governor says that is not a systemic risk, but that is a very real situation for those businesses and those workers. So, I ask you again, will you guarantee 100% of their deposits?

Hunt: You're going to have to wait and hear what the solution is, but that risk is precisely why the Prime Minister and I have been working at pace over the weekend to make sure we have a solution. These are very important companies to the UK and our future. We will have a plan to deal with their operational cashflow needs in the next few days.

This is seriously worrying.

It is why Sky News reports that major UK lenders including Barclays and Lloyds Banking Group are among the parties to have been approached by the board of SVB UK to see if an emergency takeover deal can be struck. City sources said that a number of parties, including The Bank of London, were interested in finalising a deal. Jeremy Hunt, the UK Chancellor, added more details:

“We will bring forward, very soon, plans to make sure people are able to meet their cashflow requirements and pay their staff but obviously what we want to do is to find a longer-term solution that minimises or even avoids completely losses to some of our most promising companies,” Hunt told Sky News, reiterating a statement released by the Treasury on Sunday morning.

It is why the FDIC and Federal Reserve are talking about setting up a special fund to backstop bank failures as several other smaller US banks came under pressure. In fact, similarly to the UK activities, Janet Yellen and the Biden administration have worked tirelessly all weekend to come up with a plan.

And Bloomberg reports that the global asset manager and tech lender Liquidity Group is planning to offer about $3 billion in emergency loans to start-up clients hit by the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank.

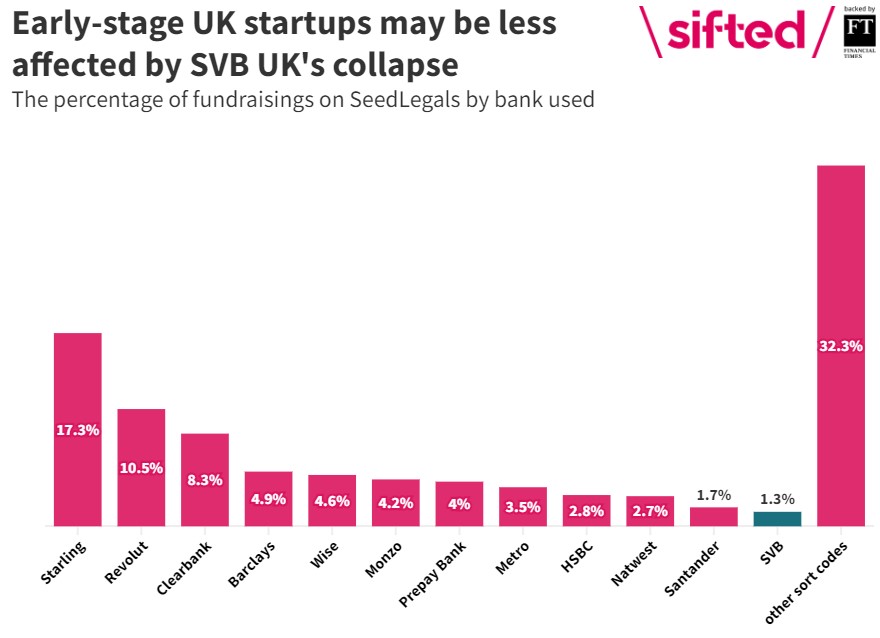

Having said all of that, ironically, Greg Becker, SVB's CEO, was talking only the other day to CNBC and said that, in 2023: “Our crystal ball is a little clearer than where it was last year”. So much for crystal balls. Equally a lot of early stage start-ups are not so reliant on SVB, according to Sifted.

At the earliest stages, companies in the UK seem to be less reliant on SVB. Only 1.3% of deals on SeedLegals, a platform which helps startups with the legals around fundraising, used SVB accounts. Most SeedLegals deals are angel, pre-seed or seed rounds.

Meantime, on the back of this, we saw other banks suffering drops because SVB’s collapse raised concerns that there might be similar problems in the debt portfolios of other lenders. At the end of last week, HSBC share price dropped 5.2%, Standard Chartered lost 4% and Barclays slid by 3.5%. Even UK domestic-focused lenders like Lloyds and NatWest fell by 2.7% and 3% respectively.

It has a ripple effect, particularly when you see a major US bank fall. Feels a little bit like a Lehmans moment? Yes and no. They’re not the same and it would take me too long to explain in this blog post.

Let’s just focus on one key element here that is similar to a Lehmans moment. The fall of SVB is a result of bad regulations in America. The collapse of SVB is very much born in the USA. Why? Because of the Federal Reserve’s interpretation of Basel III. Basel III has two dimensions of risk management for banks deposit taking versus lending ratios.

One is the “Liquidity Coverage Ratio” (LCR) and the other “Net Stable Funding Ratio” (NSFR). The first is focused upon a banks liquidity and requires you have enough cash in the bank to cover any issues of deposit taking or a run on the bank for a minimum of the next thirty days. The second is that a bank needs to ensure it has a good balance of investments between those that can be liquidated near-term, such as Treasury bills, versus those that would take longer to unravel such as mortgages and MBS securities (Ed: remember these are for ten years or more). SVB was stretched on the latter, having betted that interest rates would not rise and moving so much of their funds into MBS for yield.

Then I saw that Alphaville (a kind of blog spot for The Financial Times) spotted SVB’s most recent 10-K which stated that, due to their structure, they are not subjected to these ratios. This is because, according to Daniel Davies, author of Lying for Money, writing for Alphaville:

When the Fed implemented Basel III in October 2020, they took advantage of the fact that strictly speaking, the Basel Accords are only internationally agreed to apply to “large, internationally active” banks. While most jurisdictions apply the Basel rules to their entire banking system, the US has a strong and powerful community bank lobby, and US community banks are aggressive in their use of the borrow-short/lend-long business model.

The result of this is that only multinational American banks were subject to the full Basel III rules and ratios on liquidity and funding. SVB, even though it is (was) America’s sixteenth largest bank in the US by balance-sheet size, because of its status as a mainly domestic American bank, according to the bank’s 10-K statement, was therefore able to dodge the safe limits ratios, set by the Basel Accord. In their 10-K statement, they note that they are not limited by the LCR and NSPR Basel III arrangements.

Trouble is, that this is what has caused the bank to collapse.

Oh, and even though SVB claimed it was not a multinational bank under the US rules, it’s overseas subsidiaries such as SVB in Britain, collapsed too. This was when SVB UK applied for £1.8 billion in short-term emergency funding, via its discount window facility, and the Bank of England stepped in and said no. Why did it need such emergency funding? Because, like its American counterpart, UK start-up founders began moving their money en masse on Friday, as confusion mounted as to whether funds deposited in SVB UK accounts would be protected, regardless of what went on in the US.

UK Gov needs to focus upon this as, according to my reading, over 100 UK tech firms fear they could go under if the government does not step in. The only hope right now is the Bank of London, who launched a rescue bid to save SVB UK and, meantime, UK Government is guaranteeing to sort it out. According to Sifted:

The UK government will likely step in to address the consequences of the UK subsidiary of Silicon Valley Bank being put into insolvency proceedings on the country’s tech ecosystem. Two sources close to the government told Sifted they are confident that Rishi Sunak’s administration will make a move before Monday to ensure that SVB has liquidity and startups can make payroll.

They better as, in Silicon Valley, workers found their corporate credit cards had stopped working. Thousands of pay cheques didn’t arrive; venture capital firms opened emergency credit lines to start-ups who could not access cash in their bank accounts. Landlords demanded that tenants produce new letters of credit or risk losing their offices.

LinkedIn News also reports a few key headlines:

- Circle Internet Financial, which operates USD Coin, a digital stablecoin, said it had $3.3 billion tied up in Silicon Valley Bank. As a result, the virtual currency fell below 87 cents on Saturday, according to CoinDesk.

- Silicon Valley Bank has been put under the control of the US Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, which is serving as the tech lender's receiver.

- According to the FDIC, insured depositors will have access to their deposits by Monday morning, at the latest.

- Some analysts and investors are arguing that Silicon Valley Bank's downfall is an indicator that interest rate hikes have been too aggressive, The Washington Post reports.

Finally, is this another nail in the fintech and crypto coffin?

For more on these themes, you can also checkout Alex Johnson's deep dive here and Alfonso Peccatiello's piece on LinkedIn, which provides compelling insights into the moral hazard that SVB's management team were playing with. I also liked Marc Rubinstein's piece on Net Interest and Eddie Domez's LinkedIn update. It's a deeper analysis on SVB's financial strategy. Other commentary that gave background was Jason Hendrich’s LinkedIn update who does, rightly, point out that the collapse of both banks – Signature Bank and Silicon Valley Bank – have a commonality, which is a lack of funding (deposits). Similarly, Simon Taylor’s Brain Food gives further analysis. Oh, and this thread is excellent if you are really into understanding what happened:

* Postnote:

HSBC takes over Silicon Valley Bank’s UK unit for £1 in rescue deal

HSBC on Monday averted a crisis in Britain’s tech sector by rescuing Silicon Valley Bank’s UK arm, in a dramatic fire sale concluded after all-night talks with British ministers led by Rishi Sunak and the Bank of England.

Postnote1:

The Federal Reserve makes clear SVB accounts are protected:

"Depositors will have access to all of their money starting Monday, March 13. No losses associated with the resolution of Silicon Valley Bank will be borne by the taxpayer."

Postnote2:

Less than two weeks before Silicon Valley Bank had sold part of its portfolio at a $1.8 billion loss and was trying to raise more capital, CEO Greg Becker sold $3.6 million worth of company stock, Bloomberg reports. Regulators shut down Silicon Valley Bank on Friday amid liquidity worries and a run on deposits — the biggest bank failure since the 2008 financial crisis. The stunning collapse has at least one notable investor calling on the government to consider a "highly dilutive" bailout of the bank.

Postnote3:

Few people will realise that Silicon Valley Bank's Chief Financial Officer's (CFO) previous jobs included being CFO of Lehman Brothers, just before they collapsed in 2008. I wouldn't want to have that reputation.

Postnote4:

What was Silicon Valley Bank to the world of startups and venture capital? Practically everything. Conceived over a poker game between two of its founders nearly 40 years ago, the firm grew into the single most critical financial institution for the nascent tech scene, serving half of all venture-backed companies in the US and 44% of the venture-backed technology and health-care companies that went public last year. And its offerings were vast — ranging from standard checking accounts, to VC investment, to loans, to currency risk management.