Written by: Marc Odo | Swan Global Investments

“What is a stock worth?” This seemingly simple question opens up a Pandora’s Box. With billions of shares of stocks traded worldwide every day answering this question might seem like an impossible task. To bring clarity to a complex question, sometimes it is best to return to the basics.

The legendary investor Benjamin Graham, once said, “In the short run, the market is a voting machine but in the long run, it is a weighing machine.”

This quote is an excellent starting point for determining “What is a stock worth?” The price of a stock is how investors “vote” for a stock in the short run. The earnings of a stock are how investors “weigh” a stock in the long run. Our discussion starts with earnings.

The Price You Pay vs. The Value You Receive

When US equity markets are pushing ever higher, investors naturally begin wondering “what are the best stocks to invest in right now?” But, as with purchasing other goods, before investors consider what stock to invest in, they should consider what a desired stock is worth?

In an age of high-frequency trading and “meme” stocks, it is easy to forget the fundamentals; that a stock represents ownership in a company. Therefore, the value of a stock should be what the company will earn for its owners. Theoretically, the price of a stock should equal its value, but theory and reality seldom agree.

Determining the price of a stock is easy; anyone with access to the internet can immediately learn the price of a stock. Determining value is much more difficult because it requires forecasting the earnings of a company out into the distant future.

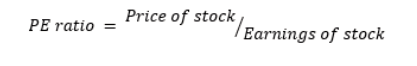

One of the most frequently used tools used by analysts to reconcile these two measures is known as the “price-earnings ratio.” At its core, it is a very simple concept[1], and is literally the current price of a stock, divided by its earnings:

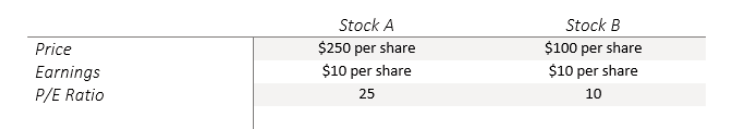

This simple metric allows us to gauge the sentiment for a stock. Consider the following example:

[1] The devil is in the details when it comes to calculating earnings. Some people use the most recent quarter or year’s earnings. Another approach is to try to forecast earnings out in to the future and produce a “forward-looking” earnings estimate. Others will adjust a company’s earnings for accounting factors like interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization. Suffice to say, determining the earnings for the P/E ratio’s denominator is the hard part.

Stock A has a high price-earnings ratio of 25. That means investors are willing to pay a high price today for a company’s future earnings. In other words, investors are bullish on a Stock A. Conversely, Stock B has a low price-earnings ratio, which implies investors are not very excited about a company’s earnings. They aren’t very willing to pay a high price for that company B’s stock- i.e., a bearish outlook.

Does this mean Stock B is a bad investment? Not necessarily. Some investors look at the above numbers and see “value” in Stock B. In the eyes of a value investor, both stocks are offering up $10 of earnings per share, but Stock B allows you access to those earnings for a much cheaper price- $100 vs. $250.

Beauty, or in this case a good P/E ratio, is in the eye of the beholder. Some would argue Stock A is the better investment, others would favor Stock B. This debate is one of the fundamental conflicts in investing, the difference between “growth” and “value” investing, respectively.

We can also view the P/E ratio from a time standpoint. The P/E ratio tells us how many years of earnings we are purchasing at today’s stock price.

- If Stock A has earnings of $10 per share and the price is $250, the P/E ratio of 25 implies that today investors are paying for the next 25 years of earnings.

- Alternatively, Stock B’s P/E ratio of 10 means it will only take ten years of earnings in order to recoup the price of the stock today[2].

Today, many stocks are trading at P/E multiples of greater than 50, meaning investors are paying for earnings all the way out to the year 2071, or longer!

Implications for Buying Stock at a High Valuation

We can also get a “big picture” view of the market by aggregating the P/E ratios of many stocks in the market. The Dow Jones Industrial Average rolls up 30 stocks; the broader S&P 500 encapsulates 500 stocks in the U.S. market. By averaging the P/E ratios for these indices, we can get a feel for the aggregate bullish or bearish sentiment for the overall market.

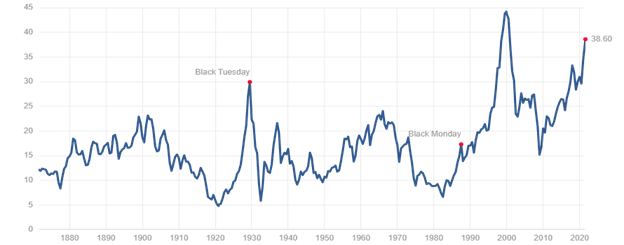

The graph below illustrates one of the more popular P/E ratios, the Shiller P/E ratio, going back almost 150 years. The current level of the P/E ratio is 38.6. In other words, it would take almost 40 years of earnings to justify today’s prices. Unless earnings improve dramatically, investors buying at today’s high prices won’t “break even” until the year 2060.

Today we are at the second-highest valuation levels in history.

Current market valuations exceed levels seen just before the Black Tuesday market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression. The only time in history the U.S. market has exceeded these levels was during the “dot-com bubble” of the late 1990’s, just before the S&P 500 entered a three-year bear market and lost nearly half its value. Avoiding such a large loss is important both emotionally and mathematically to investors’’ long-term success.

Does Stock Valuation Matter?

There exists an alternative answer to the question, “What is a stock worth?” Some people would answer, “Whatever someone is willing to pay for it.”

This is the “voting machine” dynamic Benjamin Graham described. Under this framework, a company, the business it is in, the earnings of that company, and the company’s fundamental value are all irrelevant—sentiment and momentum drive prices, not fundamentals.

In this framework, the only thing that matters is the stock’s price. The price of a stock is essentially a popularity contest. This gives way to the Fear of Missing Out (FOMO) driving investors, and not just retail investors, into stocks showing upward momentum.

It is this mindset that recently drove “meme” stocks like AMC and Gamestop to ridiculous highs. A generation ago, it was the dot-com stocks like Pets.com and Webvan that were bid up to stratospheric heights. While the names might have changed, the story remains the same.

The inherent weakness and eventually undoing of these no-earnings stocks is baked into the statement: “A stock is worth whatever someone is willing to pay for it.” If that statement is true, what happens if no one is willing to pay much for the stock in question? If there are no buyers, then a stock is worthless.

This leads to what is known as the “greater fool” theory. If someone owns a stock with no intrinsic value, the only way that person is going to make any money is to hope someone comes along who is willing to pay a higher price for a worthless stock; i.e., the greater fool.

So where does that leave us today?

An Alternative Way to Buy Stocks at High Valuations

With equity markets at all-time highs, we at Swan Global Investments are concerned about the valuation levels of U.S. equity markets. As investors seek out the best stocks to buy now and consider earnings, the “weighing machine” metrics like the P/E ratio indicate stocks are very expensive at the moment.

If one doesn’t care about earnings, the only justification for buying stocks is “because stocks are up”. If that’s the case, then one runs the risk of being “the greater fool.” Like a game of musical chairs, everyone will be scrambling in a panic once the music stops.

But there is another way: hedged equity.

Swan believes downside risk is ever-present in the market but is especially relevant today. For almost 25 years our investment philosophy has been to remain “Always Invested, Always Hedged.” Our philosophy is applied to a range of hedged equity funds and strategies that invest in the markets in order to participate in stock market gains. But we also always hedge our investments with put options that are designed to increase in value during market sell-offs.

No one knows when stocks might eventually sell off. But Swan and investors utilizing our hedged equity approach are prepared for that day.

Related: Is The 60/40 Portfolio Broken?