“ The grim irony of investing is that we investors as a group not only don’t get what we pay for, we get precisely what we don’t pay for.” – Jack Bogle

As an ode to Jack Bogle, the pioneer of low-cost investing who recently passed away, we’d like to take this time to talk about the true cost of your portfolio.

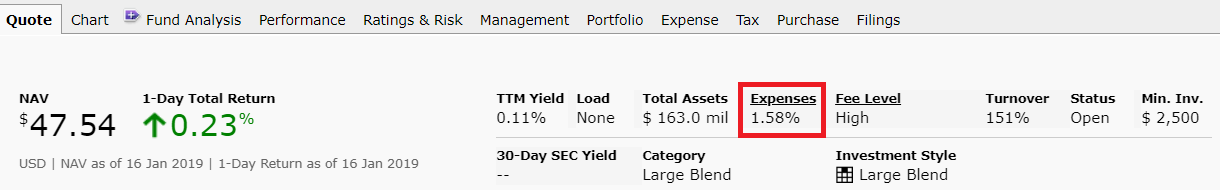

I think the phrase “it takes money to make money” is something that a large majority of the population would agree on. In fact, I think you could argue that every investment has a cost, even if you don’t realize you’re paying it. Of course, there are many different kinds of costs, but they all have one thing in common: if the money is not going back into your pocket, it’s going into someone else’s pocket.Most will scoff at the costs of their investments. Why? Usually because they are viewed in terms of percentages, and a 1-2% fee just doesn’t feel that big in the grand scheme of life. On top that, we don’t “pay” for investing the way you pay for other products. There’s no physical card or cash you are handing to a cashier at a store. This circumstance, believe it or not, allows our brains to bypass the mental hurdle of spending money, and the thoughts you have when you purchase something more materialistic, like jeans or a car. The “costs” to investing are mostly taken of your total capital via a quarterly fee (like an advisor) and/or through the fund itself.But you aren’t just losing the money as a basic, transactional cost. You are losing the ability to compound that money over time. Further, fees have a exponentially greater impact on your overall return if you have long(er) term investment horizon.Let’s look at a basic example: you have $100,000 invested. If the account earned 6% per year over the following 25 years, with no costs, you’d have roughly $430,000 at the end of the time period. On the other hand, if you paid 2% a year in costs/fees, after 25 years that same $100,000 would have grown to about $260,000. In the end, that 2% you paid every year would wipe out almost 40% of your final account value. Now, ask yourself again how much fees matter to long-term investment growth.(And capital gains distributions? Yet another easily avoidable cost that your advisor probably isn’t talking to you about.)“But I thought that higher fees would mean higher performance from these funds.” Ah, quite the contrary. Research on mutual funds has shown that higher-cost funds generally underperform lower-cost funds. That’s because the fund managers charging these costs have a difficult time adding enough value to overcome the additional expense.With all of this being said, how can one actually take control the true costs of their investments? If working with an advisor or financial planner, this should be one of your top priorities: figuring out how much the funds you own truly cost. Go grab your most recent statement and head over to Morningstar.com as a first step to personal due diligence. Type the ticker of the fund you’d like to research, and the expense of the fund (the red box in the examples below) will be one of the first things you see on the page:

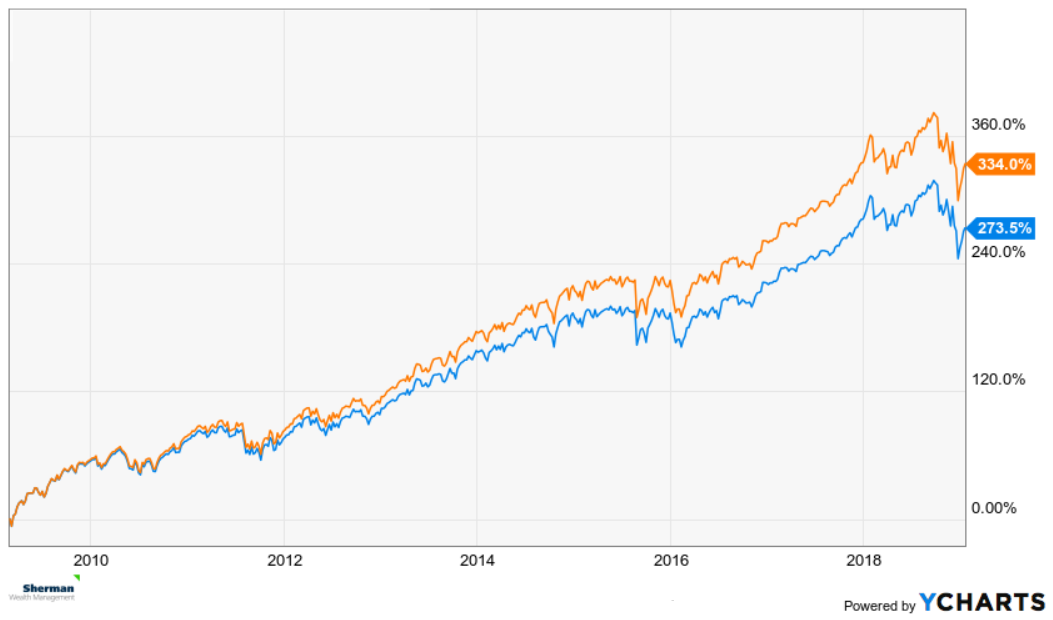

Fun fact: both of these funds track the exact same index, but their respective overall performance is quite different, as shown here:

Fun fact: both of these funds track the exact same index, but their respective overall performance is quite different, as shown here:  Related: Market Selloffs and the “Wealth Effect”If you are working with a planner who is charging you over 1% to simply manage your investments, and you are receiving no other value such as financial planning and education, I’d strongly suggest taking a hard look at the real benefits of the relationship. Why? Because your “all-in” fee could end up being substantially higher when you add in the costs of the underlying funds you have. If you discover that some of the funds you own have high expenses (0.50% and above), ask your advisor why you own these funds. It’s totally your right to do so. This is your money, your savings, your retirement. Again, there has to be more of a value-add from your advisor than simply allowing him to pick a handful of random funds to invest your money in…

Related: Market Selloffs and the “Wealth Effect”If you are working with a planner who is charging you over 1% to simply manage your investments, and you are receiving no other value such as financial planning and education, I’d strongly suggest taking a hard look at the real benefits of the relationship. Why? Because your “all-in” fee could end up being substantially higher when you add in the costs of the underlying funds you have. If you discover that some of the funds you own have high expenses (0.50% and above), ask your advisor why you own these funds. It’s totally your right to do so. This is your money, your savings, your retirement. Again, there has to be more of a value-add from your advisor than simply allowing him to pick a handful of random funds to invest your money in…