Written by: New York Life Investments

“Search for yield” was a common refrain in the wake of the financial crisis. Record-low interest rates and sluggish growth prompted a large and consistent flow of capital to higher-yielding asset classes, including private markets.

Abundant liquidity increases opportunities, but also exacerbates competitive challenges. Even before the pandemic, pressure to put money to work led to increasing valuations across asset classes. High valuations reduced return potential and encouraged investors to take on more leverage and invest in lower-quality companies.

All the while, investors feared that a disruption to liquidity would bring a “reckoning” to risky investor behavior.

Pandemic disruption short-lived, search for yield persists

The COVID-19 pandemic appeared to be that reckoning, at least for a time. But swift monetary and fiscal support helped to stabilize the corporate environment. Company defaults, while numerous, far undershot financial-crisis levels. Expectations for corporate defaults have all but moved into the rear-view mirror.

This dynamic has led investors to wonder: if the pandemic and corresponding zero-revenue environment couldn’t shake up the scale of liquidity in private markets, what can? And if an abundance of available capital keeps valuations at record levels, can investors still capture the incremental yield they seek in private markets anyway? If not, why accept the longer lockup period?

In other words: is the liquidity premium dead?

Prudent investors will tell you that just when you start wondering whether market discipline will return, it tends to surprise you. While expansionary periods tend to be constructive for both underlying economic growth and liquidity, it is important not to become too complacent. Both cyclical and structural factors could result in a damaging liquidity shock.

What could result in a liquidity shock?

Black swan: An unexpected economic or geopolitical shock results in deterioration in economic (credit) and market (liquidity) conditions. Fiscal and monetary support prove insufficient in maintaining orderly capital market functioning.

Higher interest rates: Stronger trend growth and higher inflation raise interest rates, potentially reducing attractiveness relative to public asset classes. For this to occur, we would need to see:

- Stronger trend growth: Sustained stronger productivity and labor force participation contribute to higher long-term economic growth rates, resulting in a higher cost of capital.

- Stronger inflation: If “transitory” inflationary pressures prove durable, higher policy and market interest rates would follow. (For more context, see the previous section on inflation scenarios)

- Receding international demand: The “search for yield” is not a domestic phenomenon; global appetite for U.S. assets contributes to lower market interest rates. Its abatement, whether due to the emergence of relatively more attractive stores of value or due to reduced trust in U.S. policy stability, could weaken or reverse that effect.

Market structure: A regulatory, capital, or competitive dynamic reduces the attractiveness of private assets relative to public asset classes. Investors are left without options.

Careful navigation of these risks is important for adding value on the multi-year lockup periods that private market investments require. But few investors consider these risks urgent, and many believe that demand can sustain a liquidity shock. The low-yield post-financial crisis environment pushed many investors to assess and develop comfort in private asset classes. Greater comfort with these higher-yielding asset classes makes a flight to public markets unlikely.

Beyond the liquidity premium

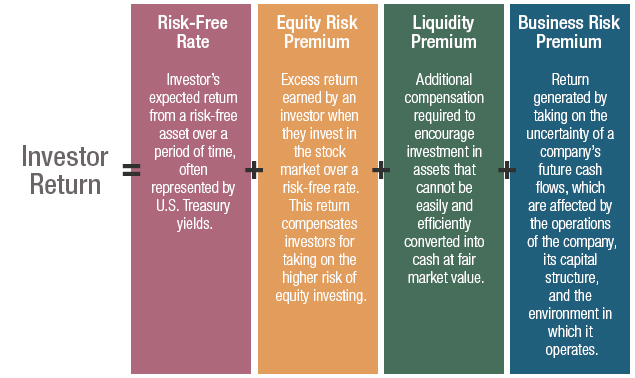

With demand for private assets posed to persist, investors have to consider other sources of value creation. Just as declines in the risk-free rate have driven investors to assets benefiting from a liquidity premium, a declining liquidity premium means investors must leverage other sources of return.

Generating business risk premium as valuations climb

Given the flood of capital to private markets, managers have record dry powder that needs to be invested. It is being invested at record valuations, which creates challenges and increases competition for investment teams. Private markets managers are often “buy and hold” investors, with lockup periods of anywhere from 3-12 years; a lot can happen in the economic environment and capital time frame during that period, reducing investors’ margin for error.

As a result, a manager’s investment thesis needs to factor in not only broader capital markets considerations, but specifically the value creation options for the business, including – but not limited to – what can be done to pivot if the macroeconomic cycle turns.

At the same time, investors face a dearth of alternatives. If the only way to capture additional yield is to lever up positions or move lower in quality, it needs more rigorous due diligence. In a recent piece , we further explore the intricacies of manager value creation.

What’s next?

There are always uncertainties in the investment environment, but they may be more pronounced after the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s not difficult to consider how financial conditions could tighten, but ample policy support and available capital make it tempting to join the trends towards higher leverage, weaker covenants, and higher risk.

Instead, investors can leverage true business acumen to add value. While there may be debate about the persistence of the liquidity premium, the business risk premium is alive and well.

All the while, the macro backdrop for private assets is strong. We expect robust growth, moderate inflation, and improving credit fundamentals in the coming years – all constructive for private investment. Low global yields likely mean that the “search for yield” is here to stay, which means flows to the sector are likely to continue.

But performance dispersion of private capital firms is wide. When testing new waters, it is essential to work with managers who have sailed in rougher seas.