Written by: Eric Winograd

With an extremely challenging 2022 now in the books, a look back reveals a year defined almost entirely by inflation. Financial markets, investors and policymakers alike in many major economies zeroed in on surging prices and what they meant for growth and asset prices.

We expect 2023 to be different—a year of transition. Inflation will still dominate headlines, likely for months to come. However, our confidence is growing that inflation pressures will start to ebb, enabling investors and policymakers to shift focus to the outlook for economic growth. The transition will herald a return to a more normal environment, though the ride will be uneven.

All Eyes Looking for Inflation Relief in 2023

Any sensible discussion of the year ahead starts with inflation—it’s still too high, and until it falls nothing else will matter as much. Based on our assessment, we’re confident that inflation will decline over the next few months, with the pace and extent of that decline determined by each economy’s exposure to key components of the inflation basket:

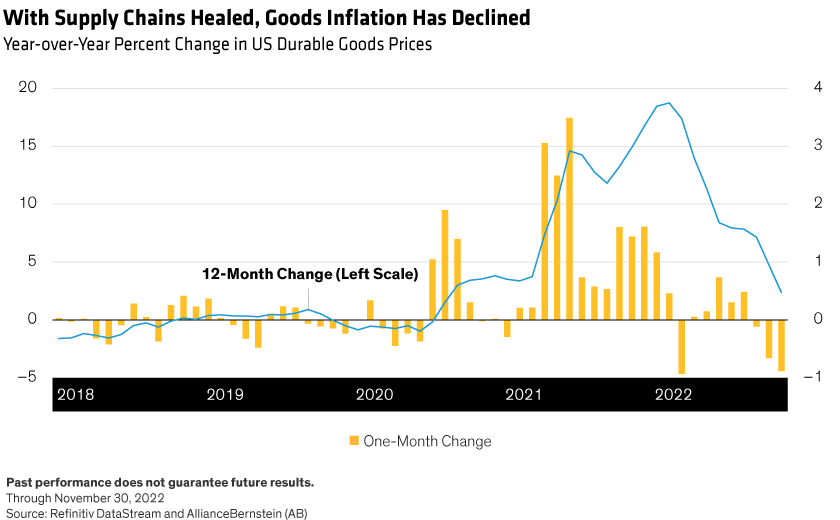

Goods inflation has started to moderate. In the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, goods inflation rose sharply as supply-chain disruptions dominated the global landscape. At their peak early in 2022, US goods prices were up roughly 20% on a year-over-year basis (Display). With supply chains now largely healed, prices have fallen over the past few months.

Commodity prices have also come down from their peaks—a trend we expect to continue—helping moderate goods inflation. Europe has the most scope for improvement, given that much of 2022’s inflation spike was driven by soaring natural gas prices in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. A mild start to the winter and effective natural-gas stockpiling will likely help pull Europe’s headline inflation—currently about 10% year over year—down sharply in the months ahead.

Shelter inflation relief is likely by summer. In the US, goods prices comprise only 25% or so of the policy-relevant core inflation basket; shelter plays the leading role. The post-pandemic surge in home prices should continue to boost shelter inflation measures for several more months, making core inflation relatively sticky. But we’re confident that the price declines we’ve seen since last spring will eventually bring those numbers down—some relief should come by summer.

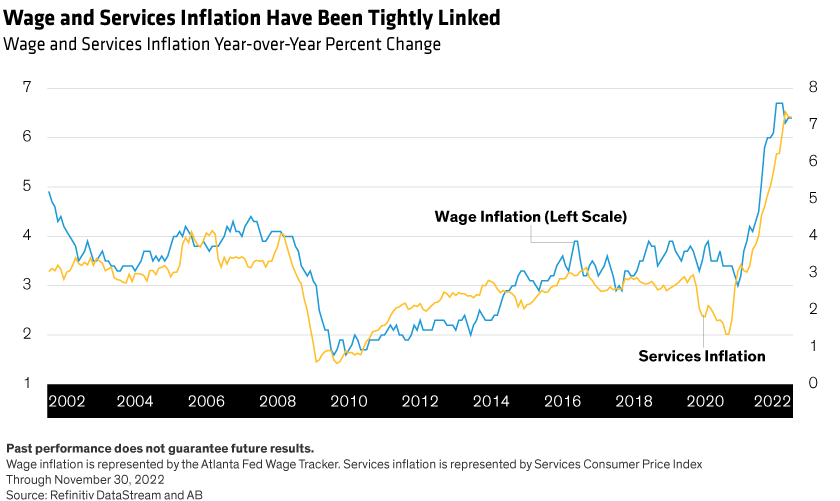

Non-shelter services inflation is still stubbornly high. Wages are the main driver of elevated non-shelter-services inflation—a metric that’s influential in both US and European price gauges. Wages are the biggest cost input for most services industries, as evidenced by the historically strong correlation between wage and services inflation (Display). It’s not surprising that the wage gains dating back to the spring of 2021 have boosted overall services inflation.

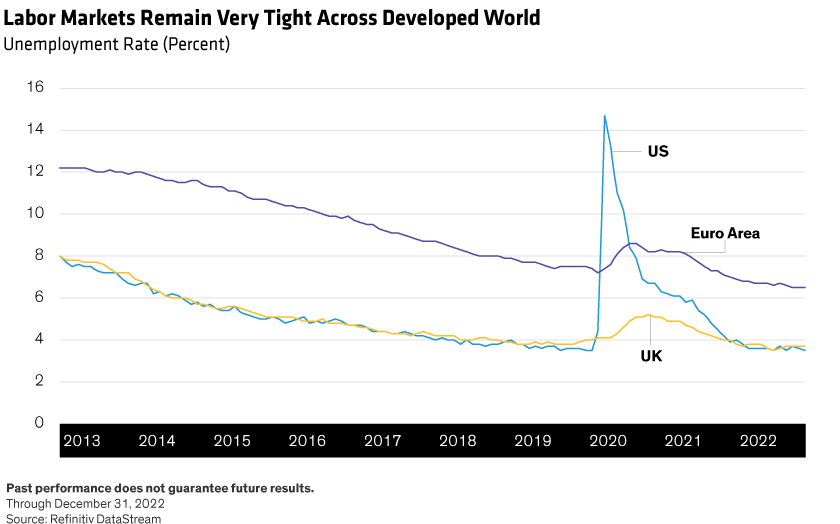

It’s here where the situation becomes tricky for many central banks. To cool wage inflation, they’ll need to tighten policy enough to slow economic growth—or possibly induce a recession. Despite sizable rate hikes in 2022, there’s still no evidence that this approach is working. Labor markets remain very tight across much of the developed world, with unemployment rates near historic lows (Display).

Tight labor markets, more than any other issue, will compel central banks to keep raising rates. We’re not as confident that wage inflation will fall as we are about declines in other parts of the basket, but monetary policy works with a long lag time. The first hikes of this cycle were only nine months ago, and we don’t think their full impact has been felt yet. So, we don’t think it makes sense to give up on the idea of softer wages, and therefore softer services inflation, going forward.

Interest-Rate Cuts Unlikely Anytime Soon

Still, the wait will be uncomfortable. Until labor weakens, the transition we expect in 2023 can’t really get under way—central bankers will likely stay hawkish. Once labor softness becomes evident, financial markets will likely shift more focus toward economic growth. Good news isn’t likely on that front: we forecast recessions in both the euro area and UK, and near-zero growth in the US for 2023.

Normally, that sort of weak growth would trigger aggressive monetary policy easing, but that won’t be in the cards for 2023. Inflation will probably cool gradually and in halting fashion, with a full convergence to inflation targets unlikely. That’s why we think central banks will pivot more slowly than financial markets seem to expect. The result: by midyear, growth should be slow or negative but policy rates still high and stable. If rate cuts happen, it won’t be until the end of this year or even into 2024 or beyond.

Asia Is Doing Its Own Thing—in Both Directions

While major Western economies are more or less on the same track—even if at different speeds—major Asian economies are on a different journey.

In Japan, inflation is just now starting to rise fast enough to catch the attention of the Bank of Japan (BOJ). The policy rate is still negative, and yield-curve control remains in effect. We expect both to change in 2023, so the BOJ will be moving toward tighter policy even as the Fed, European Central Bank and Bank of England head the other way. The BOJ shift should reverse some of the yen weakness we saw in 2022.

China, too, is in a different cyclical position. Pandemic mobility restrictions limited 2022 growth, and early 2023 will likely be weak, also, as restrictions are relaxed and infections likely spread more widely. That landscape will keep China’s central bank on its path toward easier monetary policy, at least for the first part of the year.

Expect a Choppy Year for Financial Markets

What does all this mean for investors? The good news is that 2023 probably won’t be as challenging as 2022. Even if inflation falls only gradually this year, it will take pressure off of interest rates, especially since we think rate hikes will likely wrap up in the first few months of the year. An end to the hiking cycle should provide relief to stock and bond markets.

But it’s too early to sound the all-clear. A world with slow or negative growth and restrictive monetary policy is hardly favorable for financial assets, so expect a very choppy year. Markets will rally when inflation falls faster and boosts hopes of rate cuts. But markets will also stumble when inflation falls more slowly—or when central banks push back on the idea of easing. Expect that “good-news, bad-news” push and pull to last through most, if not all, of 2023.

We see a more favorable environment by 2024, with inflation more clearly under control and policymakers more inclined to boost growth. That makes 2023 the transition year from the woes of 2022 to the more benign environment we expect to see a few quarters from now. However, transitions can be challenging—2023 may be better for markets than 2022, but the ride will be anything but smooth.

Related: Rebuilding Conviction in Stocks for a Changing World