Written by: Atul Bhatia, CFA |RBC Wealth Management

We examine the infrastructure and social legislation proposed by Congress, and look at what it could mean for U.S. growth and inflation.

U.S. fiscal policy looks to be coming into broad focus. House Democrats appear to have the votes needed to pass the nearly $1 trillion traditional infrastructure bill—if a broader approximately $2 trillion fiscal package can make it through the House and Senate.

At the same time, details are sparse on the final version of the larger budget bill. Compared to the initial Biden plan, some programs will likely be scrapped, but the general approach seems to have been reducing benefit size—either through caps or means testing—or reducing the duration of a program, cutting funding from a decade to a few years. Any required tax increases are also expected to be lower than initially proposed.

Running to stand still

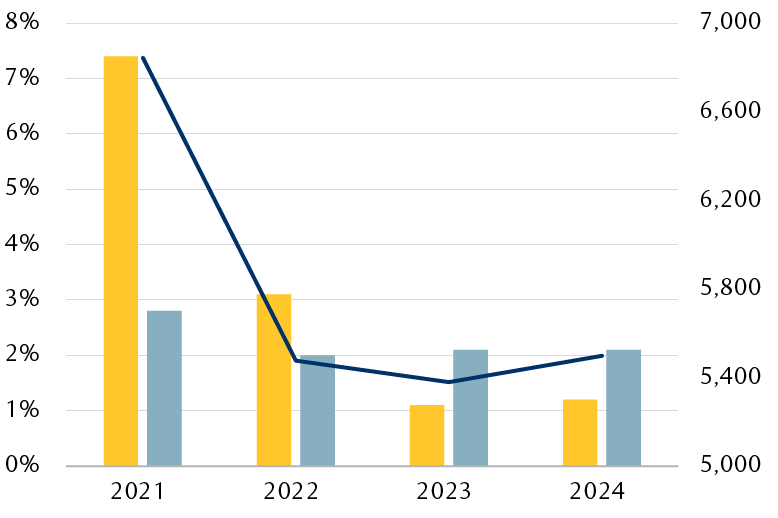

We think it is important for investors to keep in mind that even with the bills under consideration, federal spending is likely to shrink next year. Absent any new fiscal package, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) expects government outlays to fall by nearly $1.3 trillion in 2022 with further declines in 2023. This drop in spending—a direct input into the GDP calculation—is one reason the CBO estimates the U.S. economy will grow by only 1.5 percent in 2023. The legislation currently under consideration would reduce the drag from declining federal spending, but is unlikely to fully eliminate it, given the multiyear rollout for most programs.

Projected decline in GDP mirrors upcoming federal spending drop

Source - Congressional Budget Office and RBC Wealth Management

Any federal fillip to demand may be unnecessary, however, depending on the behavior of U.S. households. During the pandemic, households have ramped up their pace of savings and accumulated nearly $1.8 trillion in deferred consumption. If this war chest is spent on consumer goods and services, a federal boost to demand is likely unnecessary; if most of it remains as savings, however, reducing the GDP drag from falling government spending is likely helpful. Complicating the analysis is the distribution of wealth gains, as savings- and investment-focused household groups have tended to do the best during the pandemic.

Growth versus inflation

The legislation under consideration will likely benefit certain industries and sectors more than others, and the long-term advisability of these programs depends in large part on one’s political viewpoint. Looking only at the short-term macroeconomic implications, though, the wisdom of passing fiscal measures at this point largely boils down to a view on the relative risk of excessive inflation versus disappointing growth.

Additional federal spending is almost certainly growth positive over the next two years, in our opinion. Arithmetically, ramping up federal spending has a direct, dollar-for-dollar impact on reported GDP. In addition, the types of programs currently before Congress tend to benefit households with a higher propensity to consume, another direct driver of GDP. Even if funded by higher taxes, the net effect of the proposed budget changes is likely to be growth-positive in the near future, although changing incentives and investment patterns could lead to a different long-term outcome.

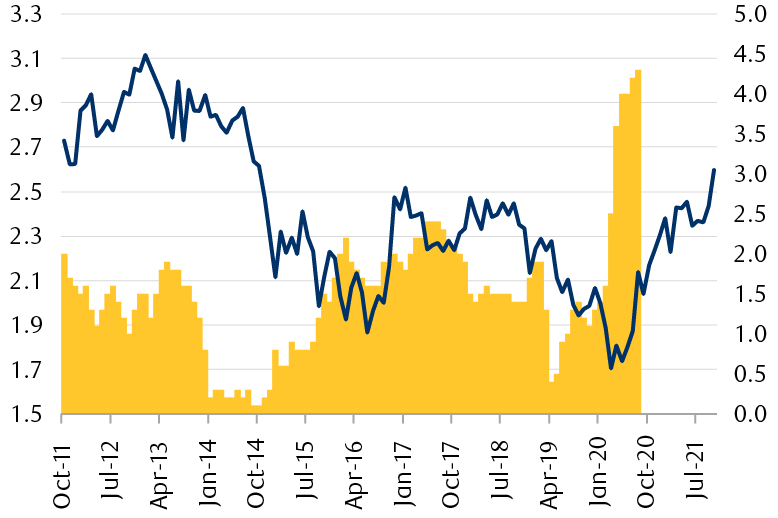

At the same time, an increase in consumption is also likely to contribute to faster inflation, and recent data has already shown higher and more persistent price increases than the Fed expected. Markets are increasingly focused on the potential for a sustained increase in prices, with medium-term inflation expectations recently hitting the highest levels in nearly a decade.

Inflation expectations are on the rise, but predictive power is weak

Source - RBC Wealth Management, Bloomberg

But as was discussed in a previous article, the degree of concern around inflation may be misplaced. The rise in “sticky” prices has been significantly slower than in more flexible prices, an indicator that inflation may not persist. The rate of increase in core prices has also slowed, with the month-over-month increase in the Consumer Price Index ex-food and energy down to only 0.2 percent, well within historical context. And inflation expectation measures—even the market-based ones—tend to be very poor predictors of actual inflation, consistently overestimating future inflation readings. Finally, the same higher energy prices that have contributed to recent price increases have historically been a leading indicator of declining future inflation rates.

One of the key risks to this view of medium-term price stability is that rising wages become entrenched, leading to an upward spiral in both demand and consumer prices. The risk is there, but for now, both the CBO and the Fed’s rate-setting Open Market Committee see the current bout of inflation as largely a one-time event; both groups estimate the Personal Consumption Expenditure price index will rise less than 2.2 percent in 2022. If wages continue to rise, we think the Fed could respond with an accelerated removal of policy accommodation, probably driving short-term interest rates higher and eventually bringing prices under control.

By providing a base of reliable demand, an increase in federal government spending could make it easier for the Fed to raise rates if needed, allowing policy normalization with a less pronounced contractionary effect.

Bottom line

As investors evaluate federal budget dynamics, we think it is important for them to separate their political preferences from their evaluation of the likely near-term macroeconomic impacts. In this case, the legislation moving through Congress is unlikely to be a near-term, economic game-changer. The total-dollar amount helps cushion the projected decline in federal spending, but with the impact spread out over many years, the growth contribution in any given year is likely to be relatively small. On balance, reducing the drag on GDP growth from declining federal spending is likely worth the potential uptick in inflation, although if price increases trigger early Fed action, any growth benefits may prove ephemeral.