Written by: Eric Winograd and Adriaan du Toit

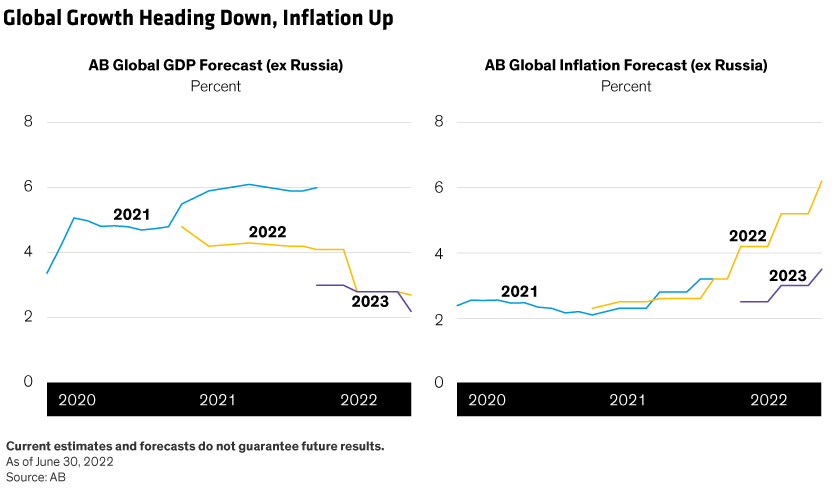

The global economic outlook has deteriorated sharply; we now expect gross domestic product (GDP) growth to be well below potential in 2023. But not all downturns are catastrophic, and once central banks can shift some focus away from inflation fighting, it should signal that an economic and financial recovery is in sight.

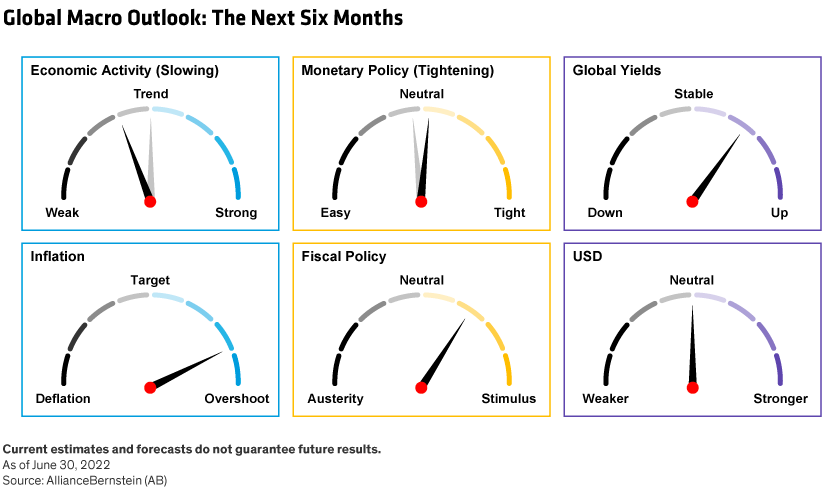

Inflation shows few signs of moderating anytime soon and central bankers are tightening monetary policy aggressively (Display). The Federal Reserve has hiked interest rates by 150 basis points so far this year and the Bank of England by 125—with the European Central Bank set to start tightening in July. Central banks from Australia to Canada and throughout the emerging world have also tightened policies—with expectations of more to come.

Recession Not Certain, but Coming Quarters Won’t Feel Good

Tighter monetary policy necessarily means slower growth, and financial markets are increasingly worried that higher rates will lead to a recession sooner rather than later. Recession isn’t a certainty, but its probability has increased in recent months.

We’ve upgraded our inflation forecasts and downgraded growth forecasts (Display): at this point, we expect growth in GDP to fall well short of potential in 2023 in almost every major economy. Whether the slowdown meets the technical definition of a recession or not, the next few quarters won’t feel good. That’s why we don’t expect relief for financial markets until inflation eases enough for central banks to slow the pace of rate hikes.

A Tough Calculus for Central Banks

One problem for central banks is that many of the forces pushing prices up are beyond their control. Supply-chain disruptions remain a problem, as the world struggles to reboot from the pandemic shutdowns. Higher commodity prices, driven upward by both supply disruptions and the war in Ukraine, have stoked the fire.

Central banks can’t fix either of these challenges with monetary policy; all they can do is hike rates and shrink balance sheets to bring demand down toward the current supply level.

That’s not an easy task. Tightening too little or too slowly could de-anchor inflation expectations, which might herald an era of unmoored inflation. Tightening too much, however, would mean a recession and—if the supply side does heal—possibly swift disinflation. Central banks started this cycle trying to split the difference—tightening only gradually. But given inflation’s staying power, monetary policy is quickly turning more aggressive.

Can policymakers design a more aggressive, front-loaded tightening cycle that minimizes downside risk? There’s good reason to be skeptical—the path to a soft landing narrows with each month of high inflation. Unless the supply side heals faster, providing some relief for prices monetary policy can’t control, central banks will have little choice but to stay aggressive—even if it triggers a negative growth outcome.

Given the challenging macro environment, it’s no surprise financial markets have struggled—indeed, that’s a critical part of rebalancing the economy. Monetary policy works through the financial system via financial markets. Higher interest rates, wider credit spreads and lower equity prices all dampen demand, which is policymakers’ objective. We don’t expect central banks to support markets in the near term, and that means more market volatility.

Putting the Economic Downturn in Historical Perspective

While the near-term economic outlook is challenging, not all downturns are catastrophic—unlike those during the pandemic and global financial crisis. Slowdowns are typically shallower, and the starting point of this particular slowdown is relatively strong.

Household finances are solid: savings are up, the labor market is strong and aggregate income remains robust. This should enable demand to slow—not collapse—at least over the next several quarters. And given the speed of this cycle, the corporate sector doesn’t seem to have built up the sort of excess leverage that often characterizes the start of economic downturns. That source of resilience should limit the damage in the coming months.

Another important point: high inflation isn’t universal. Large parts of Asia aren’t seeing the sort of price pressure that’s dominating Western nations. While central banks in the West are tightening, policy in Japan, for example, remains extremely accommodative. Chinese policymakers, both fiscal and monetary, are easing policy to try and get that nation’s economy on track.

Slippage in Emerging Economies Despite Stabilization in China

China remains a critical part of the global economy, and its zero-COVID policy and related shutdowns have been a major overhang the past few months. In a world of disrupted supply chains, getting China back online would be a major weapon in the fight to return the global economy to a more normal footing. After several disappointing months, China’s economic data rebounded late in the second quarter, suggesting an improving growth picture. We continue to forecast above-consensus growth; policymakers will likely do what’s needed to hit the official GDP growth target of 5.0%–5.5% for 2022.

Elsewhere in emerging markets, central banks (particularly in Europe and Latin America) seem near the ends of their tightening cycles. However, until tangible signs of disinflation show up, they can’t afford to let their guard down. This inflation cycle is unique, as noted earlier, and inflation risks have risen to the extent that central banks now seem willing to sacrifice growth to stop the spiral.

As a result, we’ve trimmed our emerging-market growth forecasts (excluding China and Russia). This implies a widening gap with developed markets in 2023, though this shouldn’t be seen as a positive for emerging markets—growth in both groups is projected to be below average. Also, the ramped-up tightening from developed-market central banks could force emerging central banks to extend their own tightening cycles to maintain healthy nominal interest-rate buffers. This keeps the balance of risks for the emerging-market growth outlook tilted to the downside.

The Social and Fiscal Risks of Higher Inflation

A hard global economic landing should weigh on commodity prices, and lower commodity prices should, on balance, slow inflation in emerging markets—though not as much as usual. The main reasons: food-supply challenges from the war and the risk of higher exchange rate pass-through—the transmission of global inflation to domestic prices through currency movements and pricier imports.

Higher inflation presents social risks for emerging nations and could contribute to fiscal deterioration. This is already happening in several countries, where inflationary shocks are being absorbed by increasing subsidies or by extending pandemic-related social grants to supplement disposable income. The longer it takes to control inflation, the greater the risk of fiscal fragmentation. But accelerated tightening of global financial conditions to stop the inflation spiral would also challenge emerging economies, so asset prices could remain at a crossroads until the stagflation bind moderates.

Summing Up the Big Picture

The economic outlook is challenging, with inflation stubbornly high even as growth slows. Central banks have no good options—fighting inflation hurts growth, but letting inflation run could lead to deeper dislocations. For now, inflation is squarely in the sights, even if that means lower growth and poor financial market performance.

What are we watching as we move through the cycle?

Inflation and inflation expectations are key. Once inflation moderates—which we expect—and as long as inflation expectations stay anchored, central banks will be able to pivot to put more emphasis on growth. We expect such a pivot to signal that a recovery—both economic and financial—is in sight. In the meantime, volatility should remain the dominant theme in financial markets.