Since 1979, the World Economic Forum (WEF) has annually published its Global Competitiveness Index (GCI), which, as you can probably guess, ranks the competitiveness of nations for which the group is able to gather sufficient data. This year, the WEF ranks 140 economies—from Switzerland to Guinea.

This is a report I anticipate every year because it’s an indispensable tool that helps policymakers and business leaders better understand what works and what doesn’t in creating stronger, more transparent, more efficacious societies that foster success and prosperity.

For the very curious, the more-than-400-page report is available for download on the WEF’s website.

Global Growth Starts at Home

The WEF defines competitiveness as “the set of institutions, policies and factors that determine the level of productivity of an economy, which in turn sets the level of prosperity that the country can earn.”

I agree with this definition. I often point out that government policy is a precursor to change, that such policy changes, such as the one India recently instituted regarding gold-investing , have powerful—and sometimes negative—consequences, many of them global. Here in the U.S., consider the recent implementation and impact of Dodd-Frank, or Obamacare, or FATCA (the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act).

A recent Sovereign Man post makes this point very emphatically:

"U.S. regulations have made its entire population guilty of crimes they’ve never heard of, often for the most innocent and innocuous activities.

Operating lemonade stands without a permit, collecting rainwater, failing to file a government survey are just a few activities now treated as criminal conspiracies.

And yet the government continues to publish upwards of a 1,000 pages PER DAY of new rules, regulations, and other proposals."

Presidential candidate Donald Trump, an advocate for fewer regulations, agrees. In a 2012 Washington Times op-ed , he wrote that “government regulations cost us annually $1.75 trillion. They constitute a stealth tax that is larger than the amount the Internal Revenue Service collects every year from corporations and individuals combined.”

Consider this. In the U.S., we cap debt. We cap pollution. Imagine if we did the same for rules and regulations.

Please don’t get me wrong. Every sport requires a rulebook and referee of some kind, but the game becomes increasingly difficult to play and compete in when the rules keep changing and getting more restrictive. At some point, government spending related to such rules and regulations becomes too cumbersome. The cost exceeds the benefit, in other words, as you can see in the chart known as the “Rahn curve,” named for American economist Richard W. Rahn.

I also frequently comment that governments and economic partnerships, such as the European Union, must maintain a healthy balance between monetary and fiscal policy to remain competitive on the world stage. When economies rely only on monetary policy but fail to address fiscal issues such as punitive taxation and over-bloated entitlement spending, imbalances occur. These imbalances inevitably slow the engines of business and innovation, like cholesterol in one’s arteries.

Speaking of which: Every year, the GCI lists what policymakers and business leaders identify as the most “problematic factors” for doing business in individual countries. It should come as no surprise that the top five factors on average include, in ranking order: As for gold, many CNBC reporters like to comment on the metal’s recent underperformance, when in fact gold was down substantially less than the S&P 500 Index this past quarter. Government policy is imbalanced with restrictive, choking global regulations for trade and focused instead on tax collection. We need to reform taxes and streamline regulations to stimulate economic activity.

Regarding access to finance, the GCI notes that it has worsened in recent years. This worsening is certainly the result of the global financial crisis seven years ago, but financial regulation has gone too far, paralyzing the flow of credit.

As proof of this, the group writes: “Access to finance is now almost as problematic in advanced as in developing economies.”

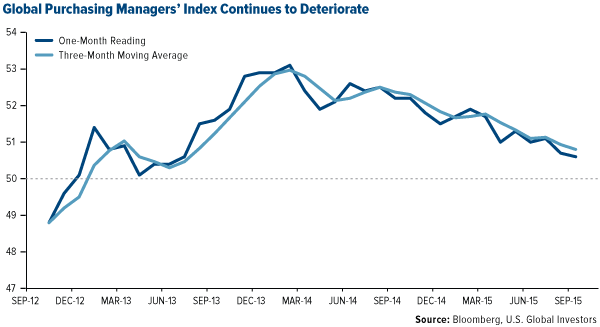

The WEF’s insight, research and guidance are as needed now as they’ve ever been. We continue to see deterioration in the global purchasing managers’ index, mostly as a result of the “problematic factors” listed above.

As large and important as China’s economy is, we can’t place the blame solely at the feet of its slowing economy for the world’s problems. If we truly wish to see an upturn in business and manufacturing activity, individual governments need to address the ever-amassing regulations, tax complexity and bureaucracy that act like sandpaper to the progress of business, innovations and prosperity.

Biggest Gainers and Losers

Before I share with you the top 10 most competitive nations—which haven’t really changed from the previous year—I want to highlight a few countries that made either some significant gains or losses.

As I shared with you in March, India was the best-performing emerging market in 2014, rising more than 29 percent. Many analysts, furthermore, estimate that the country will emerge sometime this century as the world’s third-largest economy, following China and the U.S. The country that leaped the most was India, rising 16 spots from number 71 last year to 55. I don’t think many people will find this surprising. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s election last year ushered in a new era of business development, foreign investment and anti-corruption. The “Make in India” initiative, launched by Modi in September 2014, has helped the country surpass China as the world’s top destination for foreign direct investment.

The GCI points out, however, that India continues to face significant challenges. Infrastructure deterioration, a huge lack of access to electricity and slow technological readiness are concerns Modi’s administration must take urgent action on.

Other notable climbers were the Czech Republic (gaining six points), Kazakhstan (eight points), Russia (eight points) and Vietnam (12 points). I shared with you last month that the Czech Republic has the highest PMI reading among emerging European countries and the fastest-growing economy in all of Europe, so its ascent was very much expected.

You might be taken aback, however, to see Russia rise so much, especially after the plunge in oil prices—so important to the country’s budget—the weakening of its currency and the imposition of additional sanctions following its invasion of Ukraine. The WEF no doubt anticipated readers’ disbelief as well, because it writes: “[T]his is explained mostly by a major revision of purchasing power parity estimates by the IMF (International Monetary Fund), which led to a 40 percent increase in Russia’s GDP when valued at PPP.”

As with India, no one should be shocked by this. The Marxist policies of President Dilma Rousseff, in office since 2011, have only managed to suffocate business development. Brazil ranks as one of the very worst countries in terms of burdensome government regulations, unethical business practices, effect of taxation on incentives to invest and hiring and firing procedures. The country that plummeted the most was one of India and Russia’s fellow BRIC countries, Brazil. Falling 18 spots, the South American nation now sits at number 75 out of 140, compared to last year’s 57.

Besides a loss of trust in public and private institutions because of rampant corruption, the GCI cites Brazil’s “large fiscal deficit,” “rising inflationary pressure” and “weak macroeconomic performance.”

Another BRIC country, China, holds steady at 28. You might recall that back in August, I reacted to the news of China’s stock market correction and economic slowdown, writing that “the world’s second-largest economy has begun to shift away from manufacturing and more toward consumption and the service industries.”

My views here are quite validated by the GCI’s assessment of the Asian country’s current economic condition, stating that China must “evolve to a model” that emphasizes “demand through domestic consumption.”

Crème de la Crème

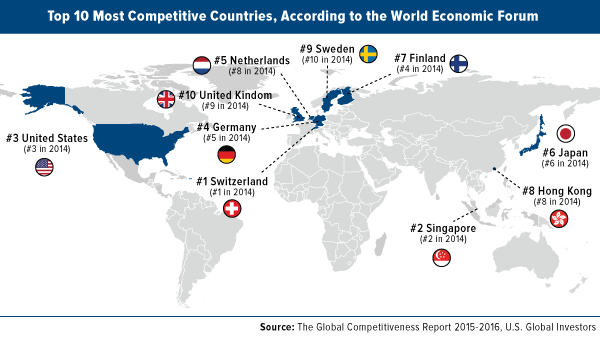

In the map below, you can see the current top 10 most competitive countries, according to The Global Competitiveness Report.

As I mentioned earlier, not much has changed since last year. No new countries have entered or exited this exalted list, and there was very little rank-shuffling. For the seventh consecutive year, Switzerland is the most competitive country. For the fifth straight year, Singapore is number two. The U.S. comes in at number three for the second year. And so on.

For this reason, I won’t spend much time rehashing what I already said in my coverage of last year’s report. It’s likely you can already identify many of the probable reasons why these nations appear so highly on the index: access to good infrastructure and electricity, quality education and research institutions, availability of the latest technology, strong intellectual property rights and protectionism and much more.

Each one of these 10 countries has its own unique strengths and weaknesses, for sure, but the common theme among them can be traced back to the WEF’s definition of competitiveness. The most successful countries foster “institutions, policies and factors that determine the level of productivity of an economy, which in turn sets the level of prosperity that the country can earn.”

Recall my comparison of Singapore and Cuba in a March Frank Talk. Both small island-states were established in their present forms in 1959—but with two starkly different economic visions. Whereas one government chose to stress sound fiscal policies and an open business environment, the other all but abolished private enterprise.

As a result, Singapore is today the second-most competitive nation on earth, according to the World Economic Forum. Meanwhile, Cuba doesn’t even rank among the 140 countries the group studied.

To get global growth back on track, it’s imperative that countries follow the leads of Switzerland, Singapore, the U.S. and others that made it to the top of the WEF’s list.