No matter where you look in the market, there are signs of exuberance. As discussed previously, stock market bubbles are about psychology. Throughout history, bubbles are a function of the extraordinary popular delusions and the madness of crowds.

Of course, that is also the name of Charles Mackay’s book, an early study in crowd psychology. The text, first published by Mackay in 1841, debunked everything from alchemy to economic bubbles. However, the three chapters on economic bubbles received praise from the likes of Michael Lewis and Andrew Tobias.

Essential is the understanding of the role psychology plays in the formation and expansion of financial manias. From the 1711 “South Sea Bubble” to the 2000 “Dot.com crash,” all bubbles formed from a similar “panic” by investors to chase ongoing speculation.

Importantly, in all cases, the speculators involved all thought “this time was different.”

Bullish Psychology

William Bernstein, who updated Mackay’s work, suggests that:

“Bubbles are characterized by extreme predictions, tend to dominate conversations and induce people to leave their jobs. The warnings of bubble skeptics get invariably met with scorn and derision.”

Of course, there is nothing “fundamental” included in that definition. As stated, market bubbles are a function of “psychology,” as investors’ herding behavior drives prices higher. Therefore, price and valuations are only a reflection of that psychology.

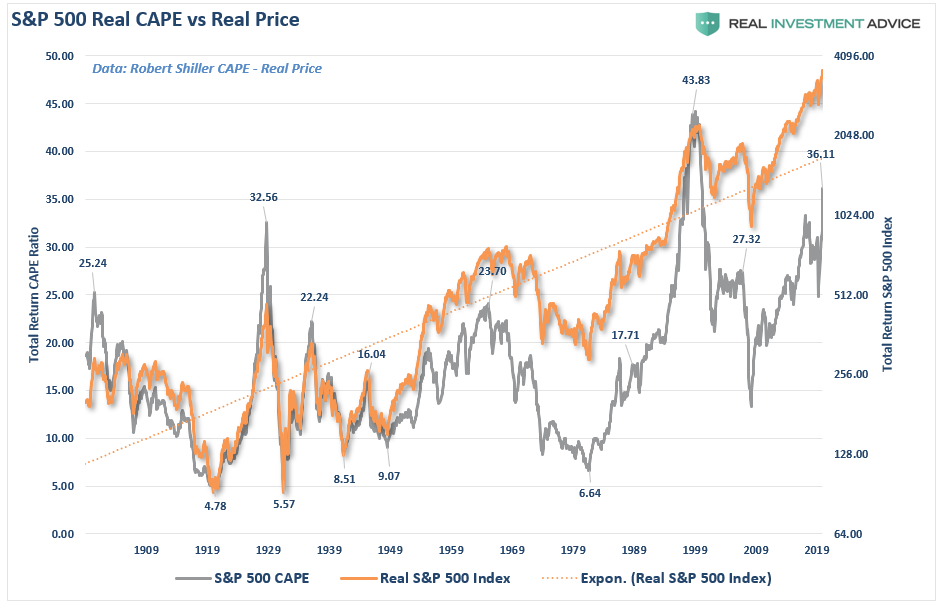

“In other words, bubbles can exist even at times when valuations and fundamentals might argue otherwise. Let me show you an elementary example of what I mean. The chart below is the long-term valuation of the S&P 500 going back to 1871.”

“Notice that except for only 1929, 2000, and 2007, every other major market crash occurred with valuations at levels LOWER than they are currently.”

Secondly, all market crashes, which resulted from the preceding bubble, resulted from things unrelated to valuation levels. Those catalysts have ranged from liquidity issues to government actions, monetary policy mistakes, recessions, or inflationary spikes. Those events were the catalyst, or trigger, that started the “reversion in sentiment” by investors.

What both Mackay and Bernstein suggest is that market bubbles really should be defined as “psychological manias.”

Confirmation Bias

One of the signs that you have entered into a mania phase is when people have trouble absorbing non-conforming information. “Confirmation bias” is a psychological behavior where individuals disregard any information which conflicts with their current beliefs. While that bias has always been problematic for investors, in recent years, as individuals lock themselves inside their “social media echo chambers,” it has worsened.

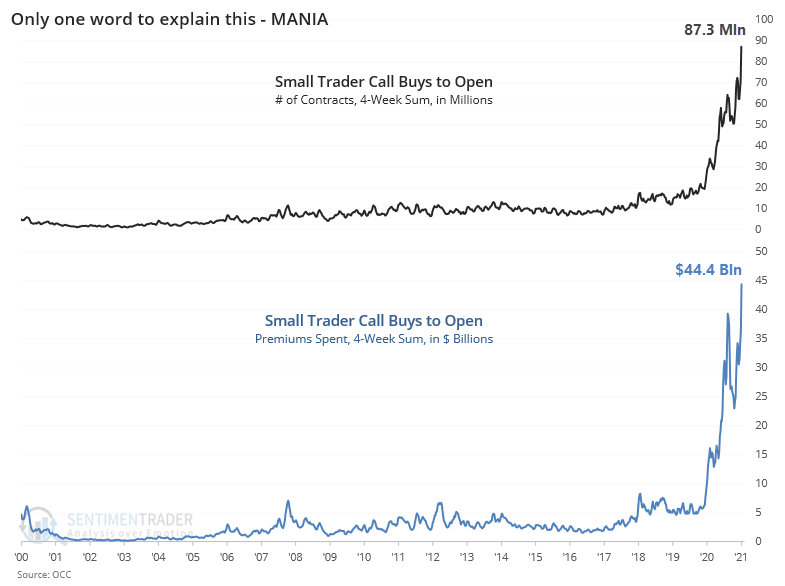

There are currently many signs of exuberance in the market from retail traders. Most notably has been the surge in speculative “call option” buying. As shown by SentimenTrader.com, despite the recent correction, retail traders got even more aggressive.

This type of behavior is the “can’t lose” mentality of investors in the market, to MacKay’s point. Such is not surprising, given that every market decline over the last decade got repeatedly met with Federal Reserve interventions. Such fostered the belief the Fed effectively established an “insurance policy” for investors to protect them from loss.

The “perception” of “insurance” emboldened investors, both retail and professional, to take on increasing levels of “risk,” as there has been no penalty for doing so. Yet.

But, as Mackay penned, such is what you would expect.

“In reading The History of Nations, we find that, like individuals, they have their whims and their peculiarities, their seasons of excitement and recklessness, when they care not what they do.

We find whole communities suddenly fixate upon one object and go mad in its pursuit. That millions of people become simultaneously impressed with one delusion, and run after it, till their attention is caught by some new folly more captivating than the first.”

More Evidence Of A Bubble

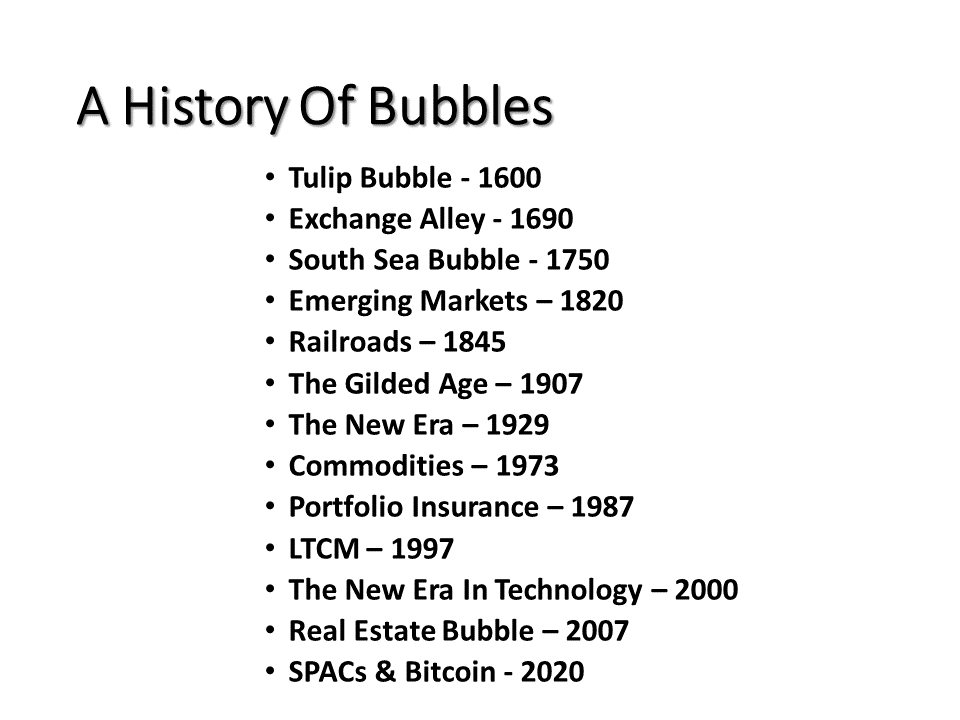

As Mackay notes, there is a long history of bubbles going back to the 1700s. The two tables below show the history of bubbles and what they all had in common.

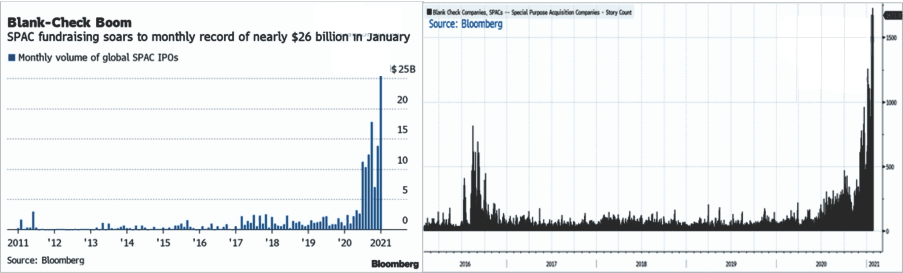

As shown below, the rush for investors to pile into SPACs (Special Purpose Acquisition Companies), or more commonly known as “blank check” companies, aligns with the long history of investor speculations.

However, it isn’t just investing in companies with “no business” in the hopes they will be able to acquire one and the chase of digital currencies (bitcoin), and companies that are solely dependent on cheap debt for issuance.

A Failure To Think Logically

While it is an unpopular opinion to suggest markets are in a bubble, the implicit denial of its existence, ironically, means otherwise.

However, as investors, recognizing that a “bubble exists” is the first step in avoiding the eventual, and inevitable, deflation when the change in psychology eventually occurs.

Does recognizing the existence of a bubble mean you sell all your investments and move to cash? Of course not.

As investors, we should think logically about the “risk” we have undertaken with our capital. The liquidity fueled bull market of the last decade forgave investors for making investing mistakes. Overpaying for value, investing in fundamentally unsound companies, and speculating without any knowledge of the investment were all forgiven by rising prices. However, when the psychology reverses, those mistakes will both be revealed and brutally punished.

Such is why investors need to have an honest assessment of the current environment, the inherent risks within portfolios, and a strategy for dealing with the eventual reversal.

The process of “thinking logically” comes down to realizing that what we currently believe to be logical thought may be nothing more than a rationalization for outright market speculation. As investors, our focus should be investing capital in a manner that ensures a return greater than the rate of inflation over time with the least risk possible.

Doing The Wrong Thing

As David Robertson pointed out previously:

“Bubbles can be hard to navigate because of their insidious ability to prey on human weaknesses. Long-term investors get lured into making short-term wagers. Risk management discipline gets discarded for a shot at spectacular gains. It is all so tempting and looks so easy. Jeremny Grantham captured this point perfectly:

‘And when price rises are very rapid, typically toward the end of a bull market, impatience is followed by anxiety and envy. As I like to say, there is nothing more supremely irritating than watching your neighbors get rich.’

So, the trouble with bubbles is they prove very tempting opportunities to do the wrong thing. Many investors will take their chances and disregard the warning. They will follow overly optimistic projections to the top and will also follow them back down to the bottom. Some will try but fail to resist the temptation. Grantham explains the challenge:

‘For positioning a portfolio to avoid the worst pain of a major bubble breaking is likely the most difficult part. Every career incentive in the industry and every fault of individual human psychology will work toward sucking investors in.'”

Such is why to survive the deflation of a bubble; we have to refocus our attention on our long-term plan and avoid psychological mistakes.

This Time Isn’t Different.

“This time is different” is the clarion call that goes up during every mania as traditional valuation measures are deemed outdated. In this respect, 2020 was no different. Professor Robert Shiller, the Yale economist who famously declared the 1990s stock market to be irrationally exuberant, recently pronounced the stock market fairly valued. By all measures, the market is more expensive than in 1929, and by some estimates more expensive than in 1999-2000. However, his justification was unprecedentedly low-interest rates.

Equally unprecedented is the disparity between the exuberance on Wall Street and the dismal reality of a virus-riddled economy.

But such is the way it always is during a bubble.

What is essential to survive a bubble is first to recognize you are in one.

That may be the most challenging part of it all.

“Men, it has been well said, think in herds; they also go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses more slowly, and one by one.” – Mackay.