Written by: Scott Minerd, Global CIO | Guggenheim Partners

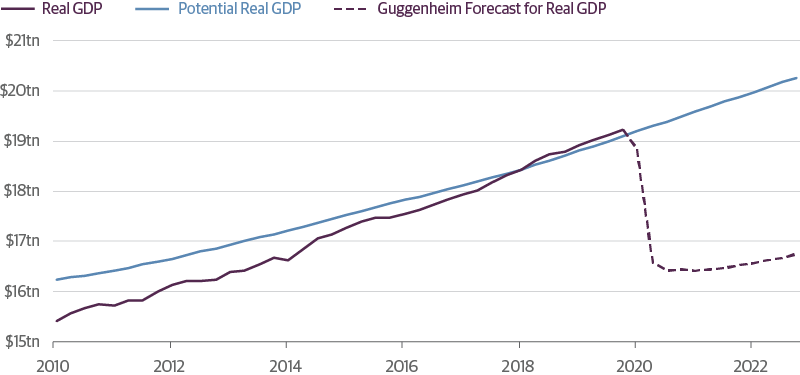

To think that the economy is going to reaccelerate in the third quarter in a V-shaped recovery to the level where gross domestic product (GDP) was prior to the pandemic is unrealistic. Four years from now the economy will most likely recover to the same level of activity that it was in January.

As this realization becomes clearer, we will be nearing the era of recrimination. Monetary and fiscal policymakers are pulling out all the stops to keep the economy and citizenry afloat during this crisis. Now is too early to determine the efficacy and durability of these crisis programs, but ultimately we will likely discover that they are insufficient, misdirected, and full of unintended consequences. Let the finger-pointing begin.

The Fed and Treasury have essentially created a new moral hazard by socializing credit risk.”

The recovery will be disappointing for several reasons. First, the end of the lockdown period is not absolute. Restrictions will only be lifted gradually, and with health experts seeing a strong chance of future waves of infections. According to a recent Harvard study, we will likely see rolling periods of lockdown going into 2022. Second, the jobs picture will not bounce back. Over 26 million people have applied for unemployment benefits in the last five weeks, more than all the total net jobs created in the 10 years of the prior economic expansion. Many of these people will not immediately be going back to work, even if the economy fully reopens by summer, which is probably unrealistic. The unemployment rate will probably spike to around 20 percent, maybe as high as 30 percent. By the end of the year the unemployment rate could still be in double digits, and then begins the long haul to get back to unemployment levels that we saw prior to the downturn. It took nearly 10 years for the unemployment rate to return to levels we saw before the Global Financial Crisis, and this labor market shock will likely be between three and five times more severe.

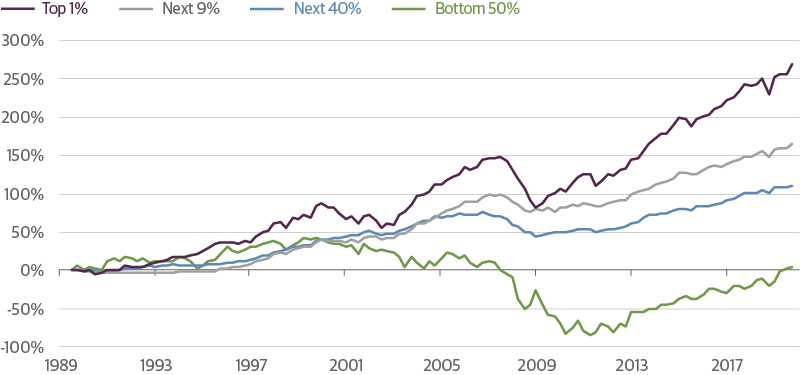

Consider that roughly half of all Americans had less than $500 in savings before this crisis hit. Most of these people were not prepared to weather a storm like this, and the damage that is being done to household balance sheets, let alone the damage to their confidence, is going to have long-term negative repercussions on consumption. Few people will immediately go out and buy automobiles and return to movie theaters. The damage to the household sector is so severe that it is going to impair living standards for most of the decade. This problem is compounded by the fact that the most financially vulnerable households are experiencing the majority of layoffs. Young, hourly workers in lower-paid service industry jobs are bearing the brunt of economic pain, and these are the people least able to deal with an interruption to income, which will compound the economic pain from layoffs as consumption falls even more sharply. Meanwhile, the disruption in corporate cash flows will be pervasive and will rebound unevenly. There will be few positive outcomes in credit as companies are encouraged to accumulate more debt in the already overleveraged corporate sector. These failures will stunt the eventual recovery and make it much more uneven.

Policymakers have put in place numerous programs that are intended to soften the blow of the crisis. The increase in unemployment benefits was a phenomenally good idea. But sending checks for $1,200 to households does very little to solve the problem, because these payments are not targeted. Many people who are working and doing fine are going to get a check they don’t need. The people who really could use the money need more than $1,200. Longer-term, stronger incentives need to be put in place to get people back to work, such as introducing a payroll tax holiday for a period of time, along with entitlement reform.

The CARES Act Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) is another great idea. However, programs that cover this wage gap during the period of lockdown are not going to solve the problem of what happens when the lockdown ends. Eventually, companies that are keeping people on their payrolls right now—which is a good idea—will find that they can’t sustain longer term employment based upon diminished demand. Programs need to be instituted to address these issues today before facing the inevitable outcome.

The CARES Act targeted funds to help certain industries, but we will discover who is and who is not helped in these programs. Companies and voters alike will soon ask, “Why didn’t I get help? You bailed out the airlines, right? You bailed out all these other corporations. But you didn’t do anything for me.” And federal assistance still might not save the airlines. Their credit profiles are rapidly deteriorating as debt rises and earnings collapse.

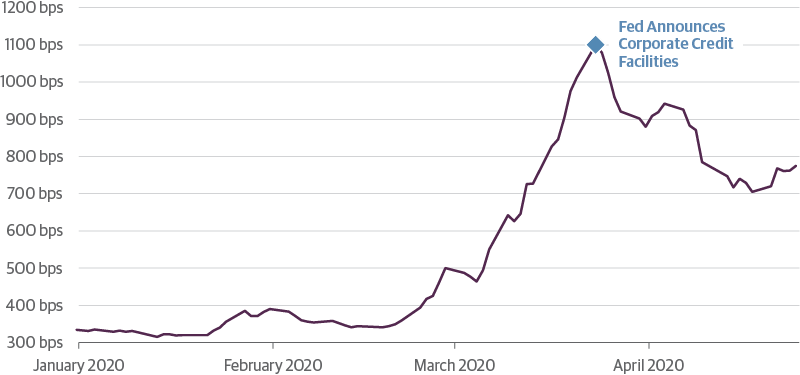

I can’t fault the Federal Reserve (Fed) for the good intentions of trying to do virtually everything in its power in a time of crisis, but the unintended consequences of its policies are considerable. Most notably, buying investment-grade and high-yield debt and providing backstop liquidity to companies has resulted in credit spreads tightening dramatically.

This policy is treating the symptoms of the problem, not the source. Many companies are even more vulnerable to damage in this cycle because they were already sitting at record levels of leverage which resulted from the low interest rate policies of the past decade and an unwillingness to allow even a mild economic slowdown or market decline. The underlying vulnerabilities in some of these industries are not being addressed. Fed purchases cannot turn bad debt into good debt. A buyer who is not careful can mistake Fed liquidity for credit strength and pay the price down the road when downgrades and defaults start in earnest.

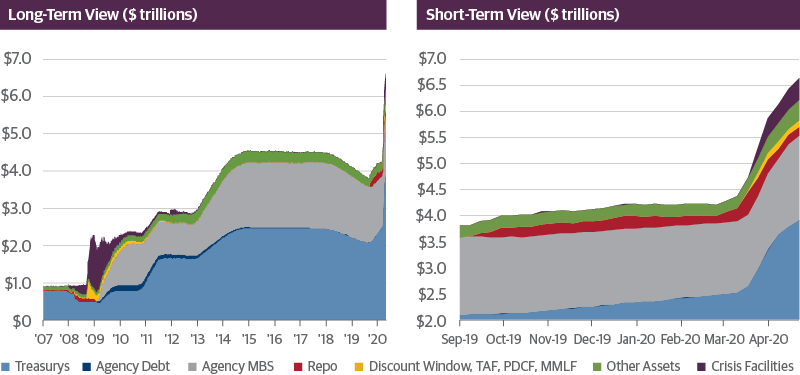

The Fed has established a new market precedent. Our central bank will never be able to get back to what was viewed as normal prior to April 9. As the nearby charts demonstrate, the Fed’s balance sheet has expanded from $4.5 trillion to $6.6 trillion in just about a month, and it is likely on its way to exceed $9 trillion soon. The Fed is not alone in this endeavor. As Ed Hyman of Evercore ISI pointed out, G7 central banks collectively purchased in March $1.4 trillion in financial assets. This annual rate of $17 trillion is nearly five times the previous monthly record set in April 2009.

If you go back 10 years to when the Fed started quantitative easing (QE), the debate was about how long QE would last and when would an exit strategy begin. I remember saying to people at the time, “The Fed will never be able to end quantitative easing; it’s here forever.” And now the new Fed backstop for credit for corporate America is here forever.

My fear is that this policy blunder will have long-term implications for our society. The Fed and Treasury have essentially created a new moral hazard by socializing credit risk. The United States will never be able to return to free market capitalism as we knew it before these policies were put in place.

The era of recrimination will have broad political and social implications. As the death toll mounts it will be used as political fodder. To say “These people died from coronavirus because of mistakes made in Washington” is an effective tactic. After the Civil War, politicians used the image of the Bloody Shirt to remind voters that honoring fallen Union soldiers demanded a Republican vote. Deservedly or not, today’s Republican administration will have a hard time fending off that argument. As the Hoover Administration bore the consequences of the economic collapse of the 1930s, so quite possibly the pandemic will be viewed as Washington’s failure. Eventually, a populist revolt to address the current massive inequality of income and wealth, will happen. Soon pressure will mount on policymakers to bolster the social safety net and increase things like healthcare and job security and maybe even institute a guaranteed living wage. My only concern is that it will be done in a way that is not productive for long-term growth. These programs will create incentives that will reduce overall productivity, Instead, policymakers should address fundamental reforms in the economy to restore growth and reduce inequality.

Fiscal and monetary programs that are being put in place are fundamentally redefining how the government interacts with businesses and individuals. Some programs will work, and some will not, but they will remain in some form or fashion forever. Now, we all need to figure out how to move forward, manage our businesses, and invest our capital in a new market regime.