Written by: Tracy Nolte | Advisor Asset Management

Credit and interest rate exposure are the two key levers by which a fixed income investor can modify the risk and return profile of a bond portfolio. At AAM, we have long highlighted the importance of carefully and tactically managing interest rate risk through duration exposure across the business cycle. As a result, our fixed income strategies have targeted a duration which is defensive (lower) relative to their benchmarks. Our investing thesis has been that record-low levels of interest rates would, in time, increase and that it was more appropriate to temper the adverse effects of rising rates with a defensive duration posture. We continue to believe that defensive duration exposure remains appropriate, but perhaps more importantly we believe that growing credit risks cannot be ignored. Today, there is an inappropriate disparity between the outlook for slower growth and the compensation investors are receiving for taking on credit risk.

Last week Fed Chair Powell continued to press the case that interest rates may need to be higher than originally expected and stay high longer than originally forecast. While 2023 began with broad optimism that the FOMC (Federal Open Market Committee) was perhaps close to the end of this rate hiking cycle, it became clear that the ongoing strength in consumer spending, remarkably strong employment, and persistent inflationary pressures would force the FOMC to remain more restrictive for a longer period.

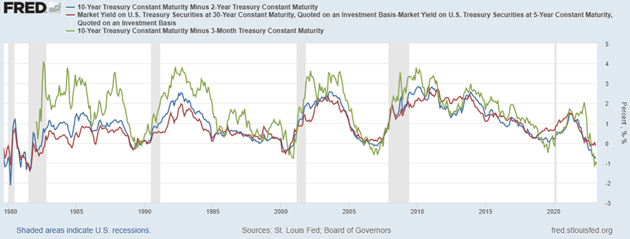

It is useful to recall that when the FOMC is attempting to slow economic activity and mitigate rising or ongoing inflationary pressures, the committee will increase their short-term policy rate and subsequently the short end of the Treasury yield curve adjusts higher to reflect this policy response. As the FOMC continues increasing the policy rate while jawboning interest rate expectations of the market, short-term interest rates respond vigorously and rise to — and often above — the level of longer-term interest rates. History shows that the shape of the yield curve, measured often as the difference between two distinct points along the curve, flattens as a result and, in some cases, inverts. The graph above highlights how curve inversions often occur prior to an economic recession. In fact, more often than not, inverted yield curves precede recessions.

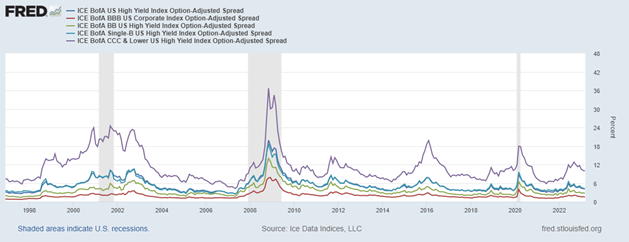

Our investing philosophy has always been that we allocate assets where we believe we are going, not where we are now. Instead of belaboring the usefulness of the yield curve as an economic indicator, we wish to use it to illustrate that given what the yield curve is suggesting today about future economic activity, credit spreads today are inappropriately tight. Looking at the charts on these pages it should become clear that at some point following a yield curve inversion, credit spreads widen in response to accelerating risk aversion as economic concerns become more acute. Recognizing that credit spreads should be widening given the economic outlook currently implied by many indicators is likely the most critical aspect in fixed income investing today.

It is worth pointing out there are some technical factors which are likely aiding and abetting low credit spreads, not the least of which is lower issuance of corporate debt. As a result, this lower supply increases the attractiveness of yield per unit of duration deeper in the credit stack. While clearly there is more credit risk in the ICE BoFA BB-Rated HY Index, the index pays a 7.33% yield versus the 5.99% yield of the BBB-rated index, and it does so with a 36% lower duration: 4.31 versus 6.69. But our belief is that some of this spread tightness may be predicated on misplaced expectations of expected risk.

It is worth noting that expectations of defaults remain low today, but they are expected to rise. Moody’s Investor Services expects corporate default rates to rise to 5.10% by the end of 2023 from 2.60% at the end of 2022. Spreads are, or should be, forward looking in that they include a probability of default as well as an estimate of a loss given a default. The more indebted a company, the lower a company’s credit rating, or the weaker the growth prospects for a firm are all should result in an investor being fairly compensated for taking on such higher credit risk. However, today we witness a yield curve inversion at its deepest level since 1981, while at the same time we see credit spreads for high yield debt approaching post-COVID pandemic highs. We may not have yet seen a meaningful default in the corporate space, but history shows us that credit stress rises when the economy slows, and it appears that credit spreads are not adequately discounting the growing probability of a meaningful economic slowdown.

Since 1960, the U.S. Economy has experienced eight recessions. During that timeframe, there have been only two periods, 1967 and 1995, when the Fed tightening cycle did not result in a recession. Again, using history as our guide, we believe that the odds of an economic slowdown are higher now than they were even a few short months ago and it is important to remember that credit risk always widens when an economy slows.

Exposure to interest rate and credit risk are the two tools through which both portfolio managers and fixed income investors alike can influence their portfolios. At AAM, we continue to stress the importance of taking a tactical approach to managing each of these aspects of a fixed income portfolio. When spreads are expected to decline, as they tend to do during the initial economic recovery, investors can monetize this by reducing their average credit quality and finding relative value in wider spreads.

However, in today’s environment with clouds looming on the economic horizon, fixed income investors should consider getting their house in order by tidying up unrewarded credit risk, allocating to well-reasoned, relative value opportunities, and perhaps keeping some powder dry. On both an absolute and a relative basis, spreads are, in our opinion, tighter than they likely will be later this year and that means tending to credit exposure as carefully as we tend duration exposure.